Ethiopian airliner down in Africa

Join Date: Nov 2006

Location: Scotland

Posts: 56

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

wheelsright:

This is the question which Boeing needs to answer.

Boeing has now revealed that the MAX had a system which compared the values supplied by the Left and Right AoA sensors. This system was supposed to flag an alert to the crew when the disagreement between the sensor values exceeded, presumably a set threshold. This AoA disagree alert was not actually implemented due to an error/oversight which the company discovered in 2017.

Thus, it seems the MAX had a means of checking the validity of AoA sensor values from day one. I cannot comprehend why this AoA disagree signal was not used by the MCAS system to inhibit nose-down trim inputs to the HS for as long as the AoA disagree signal=TRUE. Had this been done, it is unlikely the Lion Air and Ethiopian crashes would have occurred.

However, the question is why substantial disagreement between sensors was not regarded as an important factor in disabling MCAS automatically?

Boeing has now revealed that the MAX had a system which compared the values supplied by the Left and Right AoA sensors. This system was supposed to flag an alert to the crew when the disagreement between the sensor values exceeded, presumably a set threshold. This AoA disagree alert was not actually implemented due to an error/oversight which the company discovered in 2017.

Thus, it seems the MAX had a means of checking the validity of AoA sensor values from day one. I cannot comprehend why this AoA disagree signal was not used by the MCAS system to inhibit nose-down trim inputs to the HS for as long as the AoA disagree signal=TRUE. Had this been done, it is unlikely the Lion Air and Ethiopian crashes would have occurred.

Join Date: Apr 2019

Location: USA

Posts: 217

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

What is currently not well covered in any of the current 737 procedures is that a faulty stall signal that is generated by a bad airspeed or AOA input will create a number of ancillary system issues that must also be addressed. On the other end of the spectrum, an erroneous high airspeed input will cause a few problems, but not nearly as many as the low airspeed case.

Join Date: Feb 2011

Location: Grand Turk

Age: 61

Posts: 69

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Actually, I think it would be better to go into it and not take your word for it. I for one would like a full explanation. Many people are clearly missing something. PS Most people know the memory items and publications from Boeing... the issue is whether following them definitely solves the issue.

From 737 Driver

This has been mentioned a number of times, but really was the final straw that broke two airplanes.

More thorough engineering would have looked at flight path angle before trimming nose down. Airspeed and radio altimeter are also worthwhile components in determining whether additional nose down trim is advisable. But then that would increase software development and testing costs.

The Boeing press release seems to have been written by the AoA department, which apparently has nothing to do with the MCAS department

Apparently no one [at Boeing] connected the dots that by removing the control column cutout switches from the circuit, MCAS was now set up to malfunction in a novel and hazardous manner.

More thorough engineering would have looked at flight path angle before trimming nose down. Airspeed and radio altimeter are also worthwhile components in determining whether additional nose down trim is advisable. But then that would increase software development and testing costs.

The Boeing press release seems to have been written by the AoA department, which apparently has nothing to do with the MCAS department

Join Date: Dec 2018

Location: 8th floor

Posts: 0

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

It is very clear you're unable to grasp the concept of how a memory item procedure is conducted; it is certainly not how you suppose it to be. You are conflating a NNC procedure and a memory item procedure. Stop wasting our time sharing your opinions on things you know nothing about. This is rubbish speculation and it is also happens to be 100% wrong.

I found a study called "LINE PILOT PERFORMANCE OF MEMORY ITEMS" on the FAA's site that discusses among other things two conflicting concerns regarding performance under stress: doing things as fast as possible vs doing things as accurately as possible:

https://www.faa.gov/about/initiative...mory_items.pdf

From the study:

Discussions with pilot participants in this study suggest that the requirement to perform certain actions from memory implies a sense of urgency in the performance of those actions. This introduces another potential source of error due to the loss of accuracy as speed is increased, an effect that is best described by the speed-accuracy operating characteristic (SAOC). The SAOC is a function that represents the inverse relationship between accuracy and speed. As the performance of a task requires more speed, accuracy is reduced until it approaches chance. If accuracy is excessively emphasized, then the time required to complete a task increases greatly with little improvement in accuracy.

...

Using an emergency descent as an example, an earlier study [2] showed that crews performing an emergency descent from memory took longer to descend than crews using the checklist. The difference in descent time resulted from omission errors by crews performing memory items. They occasionally omitted deploying the speedbrake, causing the airplane to descend slower. On the other hand, crews that performed the procedure by reference to the checklist did not make these errors, but took longer to complete the checklist. Regardless of the time required to read through the checklist, the crews performing the procedure by reference descended to a safe altitude in less time because of the use of the speedbrake.

...

Using an emergency descent as an example, an earlier study [2] showed that crews performing an emergency descent from memory took longer to descend than crews using the checklist. The difference in descent time resulted from omission errors by crews performing memory items. They occasionally omitted deploying the speedbrake, causing the airplane to descend slower. On the other hand, crews that performed the procedure by reference to the checklist did not make these errors, but took longer to complete the checklist. Regardless of the time required to read through the checklist, the crews performing the procedure by reference descended to a safe altitude in less time because of the use of the speedbrake.

The entire study is a very interesting read. Sorry if it has been posted here before, I searched the thread and I couldn't find it.

Join Date: Apr 2019

Location: USA

Posts: 217

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Actually, I think it would be better to go into it and not take your word for it. I for one would like a full explanation. Many people are clearly missing something. PS Most people know the memory items and publications from Boeing... the issue is whether following them definitely solves the issue.

Join Date: Feb 2011

Location: Grand Turk

Age: 61

Posts: 69

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

First of all, we must recognize that MCAS is currently being redesigned and whatever techniques that are discussed here may be entirely moot by the time the MAX is cleared for operations. That being said, and assuming the MCAS design as it existed at the time of the MAX grounding, the short answer is that an "AOA Disagree" message can occur in situations where an unwanted MCAS activation would not happen. MCAS requires a number of conditions to be present before it kicks in, and disconnecting the electric trim prematurely potentially introduces other hazards into the operation. If the pilot was concerned about the potential for an unwanted MCAS activation, the two clear avenues to inhibit MCAS is to engage the autopilot or extend the flaps. Use of the autopilot was precluded in the accident aircraft due to the effects of the erroneous stall signal.

Join Date: Feb 2019

Location: shiny side up

Posts: 431

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

That statement about the first meeting seems really wrong. The AOA won't work without the plane moving through the air (preferably in the direction the nose is pointed). Because the vane has a counterweight inside it will be more than happy to sit at a random angle, until somewhere during the T/O roll the will start indicating AOA. The 400' sounds more reasonable to me, as it will give time for factors as side-slip due to crosswind T/O to dissipate.

Join Date: Apr 2019

Location: USA

Posts: 217

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

.

I understand that the memory items are so time critical that you need to be able to perform them immediately. However, when such a procedure contains "ifs" that require you to check if the problem stopped before progressing to the next step, even if you do everything in complete silence without any communication 5 seconds doesn't seem enough.

I understand that the memory items are so time critical that you need to be able to perform them immediately. However, when such a procedure contains "ifs" that require you to check if the problem stopped before progressing to the next step, even if you do everything in complete silence without any communication 5 seconds doesn't seem enough.

That being said, the accident crews really did have all the time they needed to execute the runaway trim procedure as long as one of the pilots was actively flying the aircraft, which of course includes actively trimming against the MCAS input.

Join Date: Nov 2015

Location: Bay Area, CA

Posts: 65

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

FWIW from and ex non-pilot military aircrew viewpoint, I have been in a few crappy situations when the day has just gone bad. In mil ops we operated close to the envelope in unfamiliar environments and it's the nature of these ops that means that sometimes, on thankfully very rare occasions, guys didn't come home. We all read the accident reports and make mental notes to ourselves...must be wary of that...must not do that ...must make sure I communicate that better...take another look at that checklist etc etc. But when it happens, the engine fire, the stuck main landing gear, the assymetric flap, the loss of hydraulics, smoke and fume, lightening strikes, severe CAT in the middle of an otherwise smooth moonlit cruise, flapless over the fence on short runway at 160 kts etc etc, there is a startle factor, there is time when you hear nothing and see nothing or can't make sense of anything, there is puzzlement and a fear that your event could well be the subject of the next accident report, and yes, a not unnatural fear that this could be your last flight. There is no immediate recall capacity because your senses are so overwhelmed with incoming information that you just can't assemble any course of action except whats right in your face and that leads to target fixation, like trying to control and uncontrollable wildly spinning aircraft, like trying to select the autopilot on, again and again and again!. It takes a few moments, but eventually, the haze clears. The airplane is still flying, (not in Wonkazoos case) new information is not coming and it seems like time has slowed down. Things start switching back on, you start to interpret the sounds you are hearing, the things you can see and thankfully, you start to recall memory actions. In Wonkazoos case the information didn't stop coming. Excessive and continuous G force is an overwhelming inhibitor to clear thinking. But fortunately he broke the target fixation and bailed. Everyone who has experienced hypoxia training will have experienced target fixation and how difficult it is to self recognise it let alone break it. Unlike Wonkazoos rather more desperate situation, my personal experiences were the type of things you might train for in a simulator. So much so that once you are over the startle and the haze, the immediate actions are almost routine. Importantly, you burst into pre-trained action safe in the knowledge that the event didn't kill you, that the bird still has its feathers and is flying and that if everyone does exactly as they are trained to do we'll get this thing on the ground even if the aircraft may not be reusable afterwards!

Wonkazoo and 737 Drivers' positions are so far apart but can easily be explained by the entirely different nature of events these guys have experienced and/or trained for. My experiences would lead me to agree with 737 Drivers view. That is, you get a scare, the event stabilises, you shake yourself off and go to memory recall. All going well, you, rather than someone else gets to write the event report afterwards. But now we come to ET. This should have been non-threatening 'routine' emergency. I know, using 'routine' and 'emergency' together is an oxymoron but you are trained for this right? That's why we are checked to fly. We are supposed to know what to do in these circumstances in the air because for all those recall items we maintain 100 percent recall training for them on the ground. The ET Captain would have been living under a rock and the airline grossly negligent if he wasn't aware of the Lion Air accident and what Boeing subsequently directed was his best and only courses of action to avoid disaster.

So why didn't he handled it correctly? Why didn't he just manage the UAS, turn back and land? My belief is that he didn't feel he was experiencing a routine UAS, or shall we call this a 737 Driver type of emergency, but rather that this nasty MCAS beast, that he only relatively recently become aware of, presaged by a UAS event had selected him that day. I believe there was too much information coming in for him to get out of startle mode and that this was aggravated by an early immediate assessment that he was in a fight for survival with MCAS right from the get go. He was thinking too far down track, to something that hadn't even happened yet but which led to target fixation on selecting auto pilot and his subsequent cognitive inability to deal with flaps, Vmo or cutout switches. He was not experiencing a 737 Driver "do the checklist your trained for" type of emergency but rather the "Oh no, not this" or Wonkazoo type of emergency where a fight to the death was about to start.

If the ET Captain had never heard of MCAS, he probably would have carried out the UAS and landed safely. Basically, his mere knowledge of MCAS but lack of full understanding of it may have scared the c##p out of him. How many reports have their since been of pilots that wont fly the airplane again until they are satisfied Boeing's fix and training solutions are 100 percent and in some cases others saying they just wont fly it again regardless. The ET Captain would have been deeply concerned about the possibility of a MCAS event and this self - fulfilling prophecy may have led him into the clutches of MCAS from which there was no escape.

Watch this scene from "Glory". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=90x6kAcVP54 and identify the difference between the 737 Driver correct actions and satisfactory outcomes and the Wonkazoo actions and outcomes. The soldier considers himself a pretty good shot but it doesn't take much to imagine the Colonel as MCAS and the soldier as the ET Captain. You see the soldier startle, you see his fumbling attempts to do a simple task, that previously he had done with aplomb and you see the utter disbelief at the outcome.

So sorry for the long opinionated post but I hope it provoked some thought. 737 Driver and Wonkazoo had an interesting, lively and ultimately respectful discussion some posts back from which I learnt a lot. I think ultimately they are both right..but for different reasons.

Wonkazoo and 737 Drivers' positions are so far apart but can easily be explained by the entirely different nature of events these guys have experienced and/or trained for. My experiences would lead me to agree with 737 Drivers view. That is, you get a scare, the event stabilises, you shake yourself off and go to memory recall. All going well, you, rather than someone else gets to write the event report afterwards. But now we come to ET. This should have been non-threatening 'routine' emergency. I know, using 'routine' and 'emergency' together is an oxymoron but you are trained for this right? That's why we are checked to fly. We are supposed to know what to do in these circumstances in the air because for all those recall items we maintain 100 percent recall training for them on the ground. The ET Captain would have been living under a rock and the airline grossly negligent if he wasn't aware of the Lion Air accident and what Boeing subsequently directed was his best and only courses of action to avoid disaster.

So why didn't he handled it correctly? Why didn't he just manage the UAS, turn back and land? My belief is that he didn't feel he was experiencing a routine UAS, or shall we call this a 737 Driver type of emergency, but rather that this nasty MCAS beast, that he only relatively recently become aware of, presaged by a UAS event had selected him that day. I believe there was too much information coming in for him to get out of startle mode and that this was aggravated by an early immediate assessment that he was in a fight for survival with MCAS right from the get go. He was thinking too far down track, to something that hadn't even happened yet but which led to target fixation on selecting auto pilot and his subsequent cognitive inability to deal with flaps, Vmo or cutout switches. He was not experiencing a 737 Driver "do the checklist your trained for" type of emergency but rather the "Oh no, not this" or Wonkazoo type of emergency where a fight to the death was about to start.

If the ET Captain had never heard of MCAS, he probably would have carried out the UAS and landed safely. Basically, his mere knowledge of MCAS but lack of full understanding of it may have scared the c##p out of him. How many reports have their since been of pilots that wont fly the airplane again until they are satisfied Boeing's fix and training solutions are 100 percent and in some cases others saying they just wont fly it again regardless. The ET Captain would have been deeply concerned about the possibility of a MCAS event and this self - fulfilling prophecy may have led him into the clutches of MCAS from which there was no escape.

Watch this scene from "Glory". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=90x6kAcVP54 and identify the difference between the 737 Driver correct actions and satisfactory outcomes and the Wonkazoo actions and outcomes. The soldier considers himself a pretty good shot but it doesn't take much to imagine the Colonel as MCAS and the soldier as the ET Captain. You see the soldier startle, you see his fumbling attempts to do a simple task, that previously he had done with aplomb and you see the utter disbelief at the outcome.

So sorry for the long opinionated post but I hope it provoked some thought. 737 Driver and Wonkazoo had an interesting, lively and ultimately respectful discussion some posts back from which I learnt a lot. I think ultimately they are both right..but for different reasons.

To be clear: I am agreement with most of what Mr. Driver says about training and the industry. The only real point where we diverge is on the reactions of the crews and the culpability of them or on them for the outcomes as they happened. As far as I can tell we are in agreement that industry across the board has set the stage for incidents like these, as well as that there is a ton of shared responsibility, from manufacturer to regulator to commercial operators and training systems down to (in a very minor way) the crews themselves. The difference between us is (I think) that I give the crews a pass because if all the previous people (or even some of them) had done their jobs even half competently then those six pilots would not have been sitting on a hot seat in the pointy end in the first place.

No, you cannot design an idiot-proof or perfectly safe airplane, but you can design one that won't try to kill the crews flying it if one of your data devices goes south. If you do design (and certify!!) such a contraption, no matter the cause, you should be held to very high account indeed.

Warm regards,

dce

Join Date: Apr 2019

Location: USA

Posts: 217

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

There is some suggestion that the information on MCAS was not properly distributed to the crews. However, in this case I still question whether the flaps should have been retracted given the nature of the malfunction. Even so, if the crew had first completed the Airspeed Unreliable checklist, they would have been in a stabilized aircraft at a higher altitude. Once the flaps were retracted, the erroneous MCAS activation would have presented itself as runaway stab trim. Those procedures have already been discussed, but they were not followed either. So in short, there were two well-established procedures that were not used, and if used would have had a decidedly different outcome.

Join Date: Sep 2017

Location: Europe

Posts: 1,674

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

No, you cannot design an idiot-proof or perfectly safe airplane, but you can design one that won't try to kill the crews flying it if one of your data devices goes south. If you do design (and certify!!) such a contraption, no matter the cause, you should be held to very high account indeed.

Whatever happened to the once proud and accountable philosophy driving human endeavour?

Wheelsright, #5014

Re Old MCAS. We cannot assume that crews knew of MCAS interaction with trim, (Boeing did not publish details).

With some knowledge (ET), the procedure called for use of trim and / or deduction of trim malfunction. See discussions on time assumed to recognise malfunction - MCAS active/quiescent cycle would take at least 13 sec of dedicated observation, thus probably much longer; then follow the trim runaway drill.

(5 sec could have been the value used in certification for trim runaway - but MCAS is not continuous)

An AoA alert only adds to the general confusion of several alerts consequential to AoA malfunction.

-

Re ground inhibit of AoA. As reported the logic appears reasonable. AoA vane requires airflow thus is inaccurate until xxx kts, but it is required soon after rotate for the critical stick-shake function.

Disagree provides no benefit in this, but even with contrary arguments, inhibition of superfluous alerts below 400 ft is reasonable.

I suspect that the AoA mess originates from dominant customers request for AoA display (gauge), similar to 757 option. Their reasoning driven by cost to meet the then emergent upset recovery training - we have AoA display thus less / no additional training. Boeing said yes, but possibly added the disagree alert to overcome the ‘misleading’ information certification aspect with AoA malfunction - gauges show different values but not which is incorrect.

The better engineering solution is to remove the display - AoA Disagree not required, MCAS inhibited, … no additional training, install new alert that MCAS is inoperative.

Re Old MCAS. We cannot assume that crews knew of MCAS interaction with trim, (Boeing did not publish details).

With some knowledge (ET), the procedure called for use of trim and / or deduction of trim malfunction. See discussions on time assumed to recognise malfunction - MCAS active/quiescent cycle would take at least 13 sec of dedicated observation, thus probably much longer; then follow the trim runaway drill.

(5 sec could have been the value used in certification for trim runaway - but MCAS is not continuous)

An AoA alert only adds to the general confusion of several alerts consequential to AoA malfunction.

-

Re ground inhibit of AoA. As reported the logic appears reasonable. AoA vane requires airflow thus is inaccurate until xxx kts, but it is required soon after rotate for the critical stick-shake function.

Disagree provides no benefit in this, but even with contrary arguments, inhibition of superfluous alerts below 400 ft is reasonable.

I suspect that the AoA mess originates from dominant customers request for AoA display (gauge), similar to 757 option. Their reasoning driven by cost to meet the then emergent upset recovery training - we have AoA display thus less / no additional training. Boeing said yes, but possibly added the disagree alert to overcome the ‘misleading’ information certification aspect with AoA malfunction - gauges show different values but not which is incorrect.

The better engineering solution is to remove the display - AoA Disagree not required, MCAS inhibited, … no additional training, install new alert that MCAS is inoperative.

Join Date: Mar 2019

Location: On the Ground

Posts: 155

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Not that I agree, but they make no mention of an unreliable airspeed checklist...they jump right into fixing the trim problem.

Join Date: Dec 2015

Location: Cape Town, ZA

Age: 62

Posts: 424

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

I understand that the memory items are so time critical that you need to be able to perform them immediately. However, when such a procedure contains "ifs" that require you to check if the problem stopped before progressing to the next step, even if you do everything in complete silence without any communication 5 seconds doesn't seem enough.

I found a study called "LINE PILOT PERFORMANCE OF MEMORY ITEMS" on the FAA's site that discusses among other things two conflicting concerns regarding performance under stress: doing things as fast as possible vs doing things as accurately as possible:

https://www.faa.gov/about/initiative...mory_items.pdf

This was also demonstrated in the Ethiopian flight, with the pilots forgetting to disable the auto throttles as part of the runaway stabilizer memory items.

The entire study is a very interesting read. Sorry if it has been posted here before, I searched the thread and I couldn't find it.

I found a study called "LINE PILOT PERFORMANCE OF MEMORY ITEMS" on the FAA's site that discusses among other things two conflicting concerns regarding performance under stress: doing things as fast as possible vs doing things as accurately as possible:

https://www.faa.gov/about/initiative...mory_items.pdf

This was also demonstrated in the Ethiopian flight, with the pilots forgetting to disable the auto throttles as part of the runaway stabilizer memory items.

The entire study is a very interesting read. Sorry if it has been posted here before, I searched the thread and I couldn't find it.

https://flightsafety.org/asw-article...er-error-trap/

https://human-factors.arc.nasa.gov/p...010-216396.pdf

Checklist deviations clustered into six types:

flow-check performed as read-do;

responding without looking;

checklist item omitted, performed incorrectly, or performed incompletely;

poor timing of checklist initiation;

checklist performed from memory;

and failure to initiate checklists

(in order of number of occurrence)

The first two types accounted for nearly half of the checklist deviations observed.

flow-check performed as read-do;

responding without looking;

checklist item omitted, performed incorrectly, or performed incompletely;

poor timing of checklist initiation;

checklist performed from memory;

and failure to initiate checklists

(in order of number of occurrence)

The first two types accounted for nearly half of the checklist deviations observed.

Monitoring deviations grouped in three clusters:

late or omitted callouts,

omitted verification,

and not monitoring aircraft state or position

late or omitted callouts,

omitted verification,

and not monitoring aircraft state or position

Although this study focused mainly on checklist use and monitoring deviations, additional data on

primary procedure deviations provide context and allowed us to examine how effective checklists

and monitoring were at trapping primary procedure errors

primary procedure deviations provide context and allowed us to examine how effective checklists

and monitoring were at trapping primary procedure errors

Join Date: Feb 2011

Location: Grand Turk

Age: 61

Posts: 69

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

safeteepee #5039

Do not disagree with anything in your post.

But do you think that it is possible to use electric trim to counteract MCAS before using the cut-out switches? I feel there is something being missed here. Clearly, it is intended by Boeing that you can, and that is the information that has been provided. Given, two crews appear to have failed to apply sufficient nose-up trim, I have a niggling doubt it is the whole story. I want a reason they failed to apply sufficient nose-up other than they were stupid. I realise there may not be a reason...

Do not disagree with anything in your post.

But do you think that it is possible to use electric trim to counteract MCAS before using the cut-out switches? I feel there is something being missed here. Clearly, it is intended by Boeing that you can, and that is the information that has been provided. Given, two crews appear to have failed to apply sufficient nose-up trim, I have a niggling doubt it is the whole story. I want a reason they failed to apply sufficient nose-up other than they were stupid. I realise there may not be a reason...

Join Date: Feb 2006

Location: USA

Posts: 487

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Rogue Boeing 737 Max planes ‘with minds of their own’ | 60 Minutes Australia

Compelling interviews with Chris Brady ( The Boeing 737 Technical Site ), Dennis Tajer, Peter Lemme, David Learmount and Dominic Gates.

43 minutes...

Last edited by Zeffy; 6th May 2019 at 19:13. Reason: added list of industry experts

Join Date: Apr 2019

Location: USA

Posts: 217

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

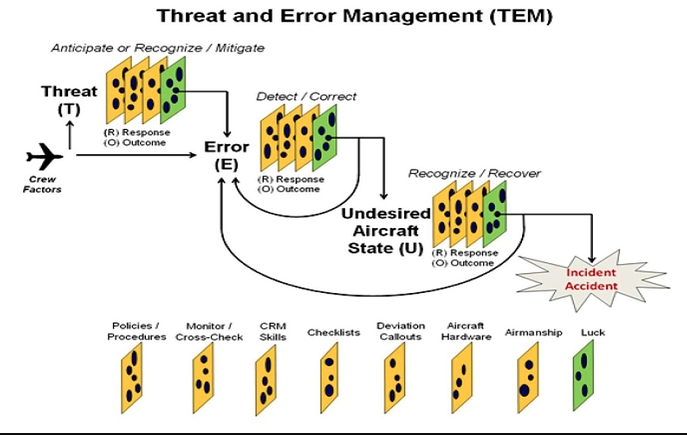

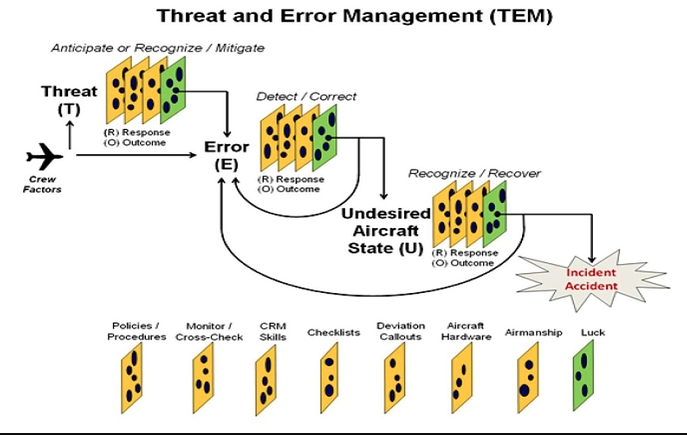

Threat and Error Management

PART 1

In the interest in moving the conversation along, and in particular to help transition this thread from a rearview, reactive mode to a more forward-looking proactive one, I would like to tee up a subject that is hopefully familiar to many aviators - the Threat and Error Management Model. I have some more thoughts to share that build upon this model, so it would be helpful to have some familiarity with it.

Briefly, the TEM model examines aviation safety through a lens that assumes that pilots will always be faced with threats (known and unknown) and errors. It is assumes that there are no perfect aircraft, environments or people, but it tries to devise a resilient system that is capable of identifying and mitigating threats and trapping errors. Rather than cut and paste a full description of the TEM model, I would ask you to look at the links below:

Introduction to Threat and Error Management

Wikipedia Threat and Error Management

Part of the TEM model is the concept of barriers. Barriers are those things that can be put in place to mitigate threats and trap errors. Some people refer this to the "Swiss Cheese" model because it assumes that no barrier is perfect either. Even though there will be holes in each barrier, the concept is to have enough of the right type of barriers so the "holes" do not line up and lead to either an undesired aircraft state or worse, an incident or accident.

.

The MAX accidents can be analyzed using the TEM model to identify not only the particular threats and errors, but also whether there were sufficient barriers and/or why the existing barriers did not ultimately prevent these accidents. Armed with this information, then the goal is to identify how those barriers can be improved to prevent future incidents and accidents.

In the interest in moving the conversation along, and in particular to help transition this thread from a rearview, reactive mode to a more forward-looking proactive one, I would like to tee up a subject that is hopefully familiar to many aviators - the Threat and Error Management Model. I have some more thoughts to share that build upon this model, so it would be helpful to have some familiarity with it.

Briefly, the TEM model examines aviation safety through a lens that assumes that pilots will always be faced with threats (known and unknown) and errors. It is assumes that there are no perfect aircraft, environments or people, but it tries to devise a resilient system that is capable of identifying and mitigating threats and trapping errors. Rather than cut and paste a full description of the TEM model, I would ask you to look at the links below:

Introduction to Threat and Error Management

Wikipedia Threat and Error Management

Part of the TEM model is the concept of barriers. Barriers are those things that can be put in place to mitigate threats and trap errors. Some people refer this to the "Swiss Cheese" model because it assumes that no barrier is perfect either. Even though there will be holes in each barrier, the concept is to have enough of the right type of barriers so the "holes" do not line up and lead to either an undesired aircraft state or worse, an incident or accident.

.

The MAX accidents can be analyzed using the TEM model to identify not only the particular threats and errors, but also whether there were sufficient barriers and/or why the existing barriers did not ultimately prevent these accidents. Armed with this information, then the goal is to identify how those barriers can be improved to prevent future incidents and accidents.

Last edited by 737 Driver; 7th May 2019 at 13:22.

Join Date: Apr 2019

Location: USA

Posts: 217

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

A careful reading of TBC-19 basically states that a bad AOA input can create unwanted stab trim movement, and the proper response to the unwanted stab movement is to execute the Runaway Stabilizer Trim checklist. I might add that functionally while experiencing this malfunction in the air, we do not refer to this document (or its equivalent). We refer to the appropriate non-normal checklist.

Join Date: May 2010

Location: Boston

Age: 73

Posts: 443

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

safeteepee #5039

Do not disagree with anything in your post.

But do you think that it is possible to use electric trim to counteract MCAS before using the cut-out switches? I feel there is something being missed here. Clearly, it is intended by Boeing that you can, and that is the information that has been provided. Given, two crews appear to have failed to apply sufficient nose-up trim, I have a niggling doubt it is the whole story. I want a reason they failed to apply sufficient nose-up other than they were stupid. I realise there may not be a reason...

Do not disagree with anything in your post.

But do you think that it is possible to use electric trim to counteract MCAS before using the cut-out switches? I feel there is something being missed here. Clearly, it is intended by Boeing that you can, and that is the information that has been provided. Given, two crews appear to have failed to apply sufficient nose-up trim, I have a niggling doubt it is the whole story. I want a reason they failed to apply sufficient nose-up other than they were stupid. I realise there may not be a reason...

Other than 'deer in headlights' loosing it I see a few possible factors:

1: Pilot accustomed to short blips not comprehending amount truly needed, this fits Lion Air when the FO was ineffective at the end when PIC handed over control while the Captain was mostly successful.

2: Trimming by column feel not position: May seem that AC is closer to trimmed than it is. In other words if you have been pulling really hard then just slightly hard may feel like close to trimmed, I am sure the pilot did not want to over trim given all the alarms.

This might explain ET first retrim at 05:4-:15. Unfortunately we don't have the column force graph, just position.

3: Some as yet to be revealed flaw that interferes with pilot trim inputs; one possibility is biomechanical factors related to actuation switches after prolonged pulling.

This is unlikely but could explain the final seconds of both accidents.

Hopefully the final reports will fully address this question.