Downwind approaches

Sure, when you're getting paid, shot at,...or rescuing a hot chick from a hoard of zombies.

I suspect some UKR helo pilots have got all three ticks in the box now

How do you make a run on landing at 0 G/S?

I think they mean that your downwash catches up with you on a downwind approach rather than you fly through your downwash.

I thought the R22 was certified to 17kts cross and downwind.

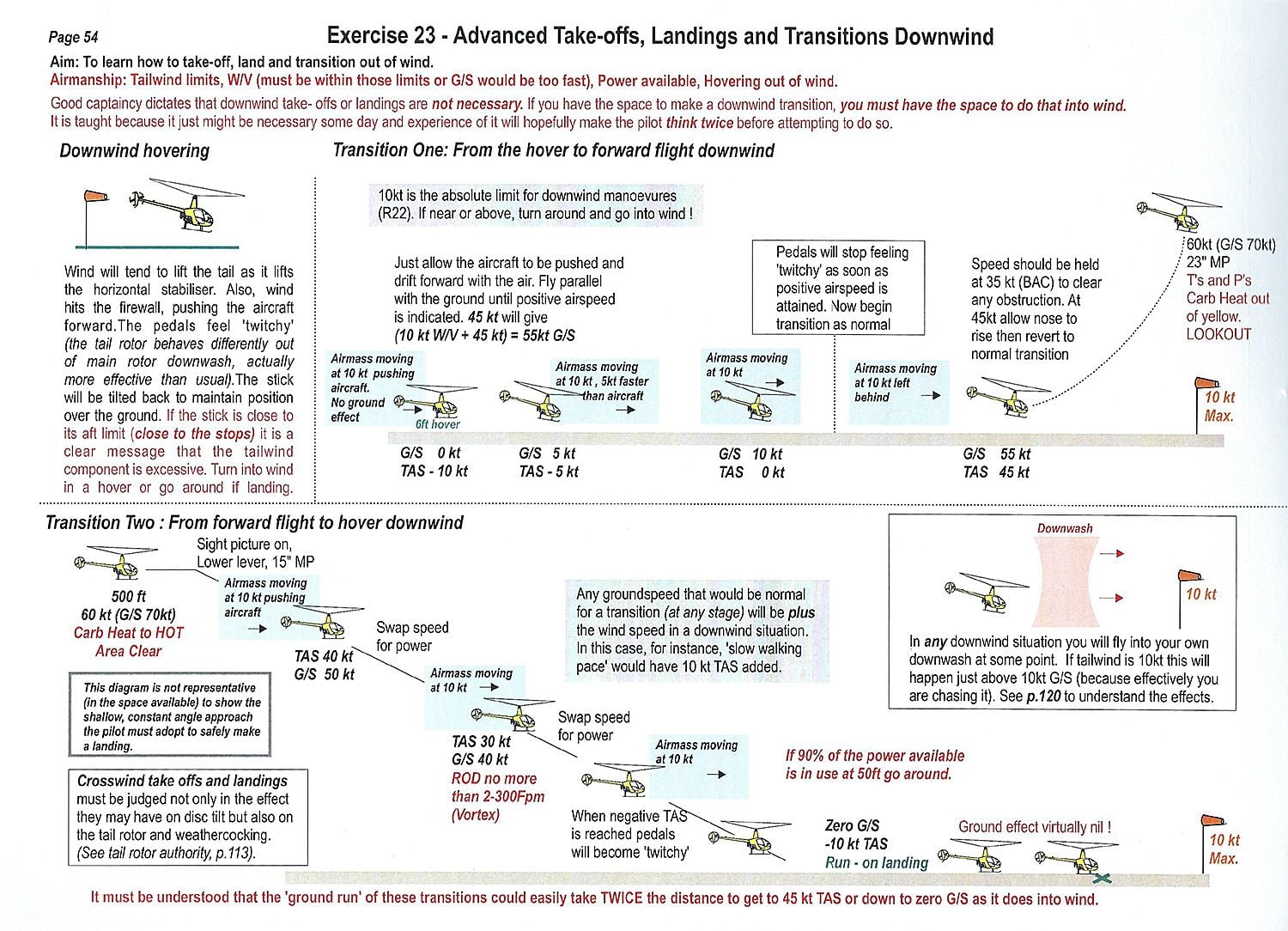

I don't quite follow their logic that if you have room to do a downwind transition then you must have room for an into wind - doesn't take into account obstacles and obstructions.

I think they mean that your downwash catches up with you on a downwind approach rather than you fly through your downwash.

I thought the R22 was certified to 17kts cross and downwind.

I don't quite follow their logic that if you have room to do a downwind transition then you must have room for an into wind - doesn't take into account obstacles and obstructions.

Join Date: Nov 2000

Location: White Waltham, Prestwick & Calgary

Age: 72

Posts: 4,153

Likes: 0

Received 29 Likes

on

14 Posts

I agree - some times next to a hill with the wind coming down it and you are full with geologists you have no choice....

I question the good captaincy statement. Good captaincy dictates that you are aware of the limitations if you choose that way.

I question the good captaincy statement. Good captaincy dictates that you are aware of the limitations if you choose that way.

The engine doesn't know you are down wind - if you have the performance and use the correct techniques, there is little additional risk over a 'normal' approach or departure.

The following users liked this post:

Originally Posted by [email protected]

The engine doesn't know you are down wind - if you have the performance and use the correct techniques, there is little additional risk over a 'normal' approach or departure.

"Just a pilot"

I would always fly approaches with the same approach angle and as slow as I could. The best approaches I flew did not require a pitch attitude change from 50 knots (Bells) or 60 knots in AS350/355 at 300' AGL, controlling angle of descent with small power/collective movements. Yes, that can be done, at least in an AS350/355 and a Bell 206 series. Elevated points of landing, especially those being in downwind turbulence may require a change in particulars...

In my opinnion 'flat' approaches make ground speed difficult to judge, potentially leading to a last minute tail-low, hard decel attitude, which could poduce complications and more hazard than one's typical slow approach and angle terminating in a stable hover attitude.

My personal favorite approach was the "high overhead" in which one is constantly turning in a continuously decelerating, descending spiral from the high recon. Delay the yaw around to align the aircraft with ground track until absolutely required. And- it may never be required depending on wind, obstructions, terrain or how you plan to position for the loading/unloading.

It is not absolutely required that the nose be pointed in the direction of travel. You can turn the aircraft sideways to observe the point of landing, ie: in the AS350 I flew on the last job, I would fly the final segment left side forward and align it at the last possible moment. It takes some practice to be able to judge angle and rate of closure with a new aspect. That's not required in an LZ that requires a vertical descent, in which case I would turn the nose such that I had the best view of most threatening obstacle.

In my opinnion 'flat' approaches make ground speed difficult to judge, potentially leading to a last minute tail-low, hard decel attitude, which could poduce complications and more hazard than one's typical slow approach and angle terminating in a stable hover attitude.

My personal favorite approach was the "high overhead" in which one is constantly turning in a continuously decelerating, descending spiral from the high recon. Delay the yaw around to align the aircraft with ground track until absolutely required. And- it may never be required depending on wind, obstructions, terrain or how you plan to position for the loading/unloading.

It is not absolutely required that the nose be pointed in the direction of travel. You can turn the aircraft sideways to observe the point of landing, ie: in the AS350 I flew on the last job, I would fly the final segment left side forward and align it at the last possible moment. It takes some practice to be able to judge angle and rate of closure with a new aspect. That's not required in an LZ that requires a vertical descent, in which case I would turn the nose such that I had the best view of most threatening obstacle.

Well, I've seen plenty of videos where guys are crashing perfectly good helicopters flirting with tailwinds. So it kinda makes this "correct technique" seem as common as what we used to call "common sense", lol.

You can fly a safe downwind approach using exactly the same technique as an into wind one - it's not a special technique never taught to pilots, it is the same technique with awareness of the differences in power requirements during the approach.

Devil, you describe an academic approach - selecting the correct decelerative attitude to maintain a constant reduction speed coupled with controlling the glidepath (approach angle) with collective. However the changing airflow over horizontal stabilisers as the rotor downwash moves off them (lower speeds) inevitably requires some cyclic corrections to be made along with the inescapable effects of flap forward (the reverse of flapback)during decel.

Most commercial and military operators wouldn't fly your slow approach way since time costs money for commercial and a slow approach makes you an easy target for military ops.

The following users liked this post:

Join Date: Nov 2000

Location: White Waltham, Prestwick & Calgary

Age: 72

Posts: 4,153

Likes: 0

Received 29 Likes

on

14 Posts

"I thought good captaincy was knowing when to say, "Sorry fellas we can't land there today, guess we'll have to go with plan B"? I mean, I'm fine risking my own life, but,...  "

"

Wait until it's getting to be dusk, the passengers are late, there is no shelter, you can't leave one behind because you won't find them again in the dark and you have to use your tricks of the trade to rescue them from their own screwups.

"The engine doesn't know you are down wind"

Neither do the rotors, except for a little dirty air from the tail rotor.

The big difference in being downwind is the lack of kinetic energy.

An aircraft flying at 30 knots into a 30 knot wind is doing that speed aerodynamically, but is stationary inertially, as it has no kinetic energy. In effect, it is hovering. On the other hand, the same aircraft with a tailwind of 30 knots possesses 60 knots’ worth of kinetic energy from its groundspeed, although, aerodynamically, the conditions are identical. If the downwind aircraft turns through 180°, it will end up with 60 knots of groundspeed and 90 knots of airspeed, so it will climb as the surplus is converted to potential energy. On the other hand, the aircraft starting with the headwind will lose height because it lacks 60 knots’ worth of kinetic energy. A heavy aircraft, or one with less power, could crash.

As long as you are aware of the power requirements and what the air is doing, I don't see a major problem. Of course it's not ideal, but, hey, life isn't perfect.

"

"Wait until it's getting to be dusk, the passengers are late, there is no shelter, you can't leave one behind because you won't find them again in the dark and you have to use your tricks of the trade to rescue them from their own screwups.

"The engine doesn't know you are down wind"

Neither do the rotors, except for a little dirty air from the tail rotor.

The big difference in being downwind is the lack of kinetic energy.

An aircraft flying at 30 knots into a 30 knot wind is doing that speed aerodynamically, but is stationary inertially, as it has no kinetic energy. In effect, it is hovering. On the other hand, the same aircraft with a tailwind of 30 knots possesses 60 knots’ worth of kinetic energy from its groundspeed, although, aerodynamically, the conditions are identical. If the downwind aircraft turns through 180°, it will end up with 60 knots of groundspeed and 90 knots of airspeed, so it will climb as the surplus is converted to potential energy. On the other hand, the aircraft starting with the headwind will lose height because it lacks 60 knots’ worth of kinetic energy. A heavy aircraft, or one with less power, could crash.

As long as you are aware of the power requirements and what the air is doing, I don't see a major problem. Of course it's not ideal, but, hey, life isn't perfect.

interesting..

so with an into wind approach the aircraft has less kinetic energy, whereas a downwind approach has more kinetic energy

this would suggest downwind approaches are safer/better. but I know they are not.

so with an into wind approach the aircraft has less kinetic energy, whereas a downwind approach has more kinetic energy

this would suggest downwind approaches are safer/better. but I know they are not.

because during an approach kinetic energy is working against you because you need power, space and time to manage and reduce that kinetic energy.

I seem to remember this downwind/into wind argument regarding energy as having been done to death before and it all has to do with the frame of reference.

I know that turning 180 from downwind to into wind won't give me extra energy or make me climb if I maintain attitude, airspeed and power - I will roll out with the same airspeed but a much lower groundspeed. Done it more times than I care to remember without ever having an unwanted climb or having to reduce power.

Aircraft crash turning downwind at low level because the pilot tries to maintain a constant groundspeed in the turn and washes off airspeed.

I know that turning 180 from downwind to into wind won't give me extra energy or make me climb if I maintain attitude, airspeed and power - I will roll out with the same airspeed but a much lower groundspeed. Done it more times than I care to remember without ever having an unwanted climb or having to reduce power.

Aircraft crash turning downwind at low level because the pilot tries to maintain a constant groundspeed in the turn and washes off airspeed.

Crab I think we need to remember that we are talking teaching new guys to fly here. So for instance hovering downwind will require more power as they are unable to hold a steady hover as into wind, different for a seasoned pilot. It is the same as making an approach, teaching downwind to a student ( lesson 26 ) one has to be careful what one teaches as they can struggle to process all the information coming into them ( helmet fire to use a UK mil term ) so best to teach a flatter approach so there is a little less going on. Remember within 45 hours they could be off on their own, with very little if any oversight !!!!

Valid points Hughes 500 and the patter I used to teach to baby QHIs (and what I was taught back in the day) included those bits of info/technique because they were aimed at basic students.

The lack of mandatory post-graduate training requirements for PPLs scares me and goes a long way to explain a number of accidents.

The main reason for using a flatter approach is to keep the RoD lower than on an into wind approach.

The lack of mandatory post-graduate training requirements for PPLs scares me and goes a long way to explain a number of accidents.

The main reason for using a flatter approach is to keep the RoD lower than on an into wind approach.

I've always thought the UK/CAA/EASA/JAR (etc) PPL(H) syllabus to be completely unsuited to training civilian pilots.

I think the 10 hours solo (ie flying under your instructors licence) is bonkers. This 10 hours should be done post PPL test, alongside some significant off-airfield "real world" dual training

And..Quickstops, why on earth are they even in the syllabus? Surely a hangover from the military?

I think the 10 hours solo (ie flying under your instructors licence) is bonkers. This 10 hours should be done post PPL test, alongside some significant off-airfield "real world" dual training

And..Quickstops, why on earth are they even in the syllabus? Surely a hangover from the military?

The following users liked this post:

Avoid imitations

Join Date: Nov 2000

Location: Wandering the FIR and cyberspace often at highly unsociable times

Posts: 14,574

Received 422 Likes

on

222 Posts

The following users liked this post:

It's also a very good method of demonstrating flare effect and how to manage the end of a flared approach with respect to power requirements - sorts the 2 o'clock daisy hoverers from the attitude flyers.

I've always thought the UK/CAA/EASA/JAR (etc) PPL(H) syllabus to be completely unsuited to training civilian pilots.

I think the 10 hours solo (ie flying under your instructors licence) is bonkers. This 10 hours should be done post PPL test, alongside some significant off-airfield "real world" dual training

And..Quickstops, why on earth are they even in the syllabus? Surely a hangover from the military?

I think the 10 hours solo (ie flying under your instructors licence) is bonkers. This 10 hours should be done post PPL test, alongside some significant off-airfield "real world" dual training

And..Quickstops, why on earth are they even in the syllabus? Surely a hangover from the military?