B17 crash at Bradley

Just seen the video of Nine-O-Nine taken when she was struggling to fly downwind. Gear down, nose looking rather high and looking very slow. Such a shame they didn't commit to a closer runway!

Join Date: Dec 2014

Location: LHBS

Posts: 281

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

WIth these exceptionally rare warbirds, there is special kind of get-there-itis, which downprioritizes controlled yet survivable crash landings, in favor of trying to achieve normal landings beyond reasonable risk taking.

We recently had a DC-3-like vintage aircraft flying back to base from an airshow with about 60% of the rudder fabric missing (it tore off shortly after takeoff).

No passengers, short flight home, but a few of us were wondering, that with so little rudder control, an engine failure could have been lethal, unless they land it en-route on a reasonably flat field.

We recently had a DC-3-like vintage aircraft flying back to base from an airshow with about 60% of the rudder fabric missing (it tore off shortly after takeoff).

No passengers, short flight home, but a few of us were wondering, that with so little rudder control, an engine failure could have been lethal, unless they land it en-route on a reasonably flat field.

Last edited by Pilot DAR; 24th Dec 2020 at 12:08. Reason: typo

Join Date: Nov 2015

Location: Paisley, Florida USA

Posts: 289

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

I agree with Scott Purdue in the above video, that the big question is: "Why wasn't the power cut when the airplane hit the approach lights?" The airplane was apparently at the point of stall when it hit the approach lights, was way below vmc and there was 9500 ft. of clear runway ahead of them. Did they try to go around? I posed that question in my post #182 of 09 Oct, 2019, titled, "Attempting to Go Around?" Why would they attempt a go around under these circumstances? I doubt we'll ever know the answer to that question.

Regards,

Grog

Regards,

Grog

Join Date: Dec 2014

Location: LHBS

Posts: 281

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

I was suprised about that sharp right turn, I only realize now how badly they deviated from the runway direction. (80 degrees or so, nearly perpendicular).

When the airplane touched down, hitting the right wingtip in a slight right bank, the pilot, whose hands were possibly on the throttle at that time, may have inadvertenly moved the power levers forward. Especially if they weren't wearing shoulder harnesses.

I find the go-around attempt a bit improbable. Not having enough power to maintain proper airspeed should have discouraged the thought of a G/A completely. The hard landing and potential wing damage should have also discouraged the go-around even more. The view of the aircraft, turning uncontrollably towards nearby buildings and away from the runway centerline should have been the final warning to cut power and brake hard and use a lot of left rudder to stay out of bigger trouble. But the aircraft appears to continue to right turn for quite some length, with no sign of trying to turn back left.

Yeah, all speculations. Maybe I am biased by a DC-3 accident during a sightseeing flight in the 60's, where a perfectly operational airplane crashed, simply because the crew was not strapped in, and one of the pilots (most likely the captain) had the brilliant idea of showing the passengers what zero G's are about.....

When the airplane touched down, hitting the right wingtip in a slight right bank, the pilot, whose hands were possibly on the throttle at that time, may have inadvertenly moved the power levers forward. Especially if they weren't wearing shoulder harnesses.

I find the go-around attempt a bit improbable. Not having enough power to maintain proper airspeed should have discouraged the thought of a G/A completely. The hard landing and potential wing damage should have also discouraged the go-around even more. The view of the aircraft, turning uncontrollably towards nearby buildings and away from the runway centerline should have been the final warning to cut power and brake hard and use a lot of left rudder to stay out of bigger trouble. But the aircraft appears to continue to right turn for quite some length, with no sign of trying to turn back left.

Yeah, all speculations. Maybe I am biased by a DC-3 accident during a sightseeing flight in the 60's, where a perfectly operational airplane crashed, simply because the crew was not strapped in, and one of the pilots (most likely the captain) had the brilliant idea of showing the passengers what zero G's are about.....

Last edited by rnzoli; 29th Dec 2020 at 16:25.

Join Date: Dec 2014

Location: LHBS

Posts: 281

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

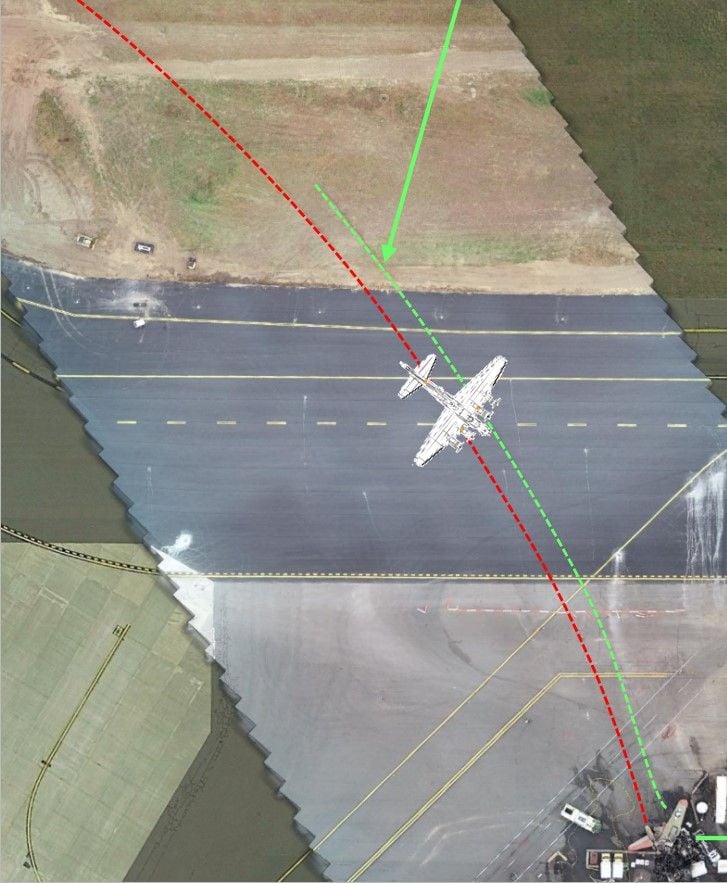

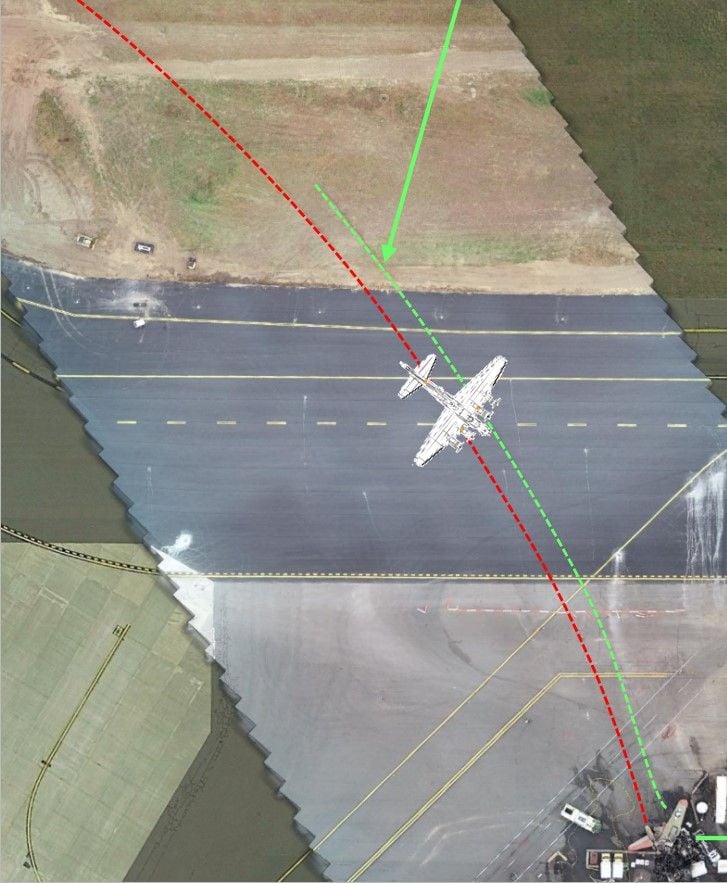

By the way, if you look at figure 15 of the UAV report, it claims that there is an additional tire mark from the tail wheel.

The problem is: it is outside of the right MLG tire marks!

What are the chances that the right tire punctured when hitting the lights and the marks are actually created by a flattened right tyre, also pulling the aircraft to the right?

https://data.ntsb.gov/Docket/Documen...-FINAL-Rel.pdf

The problem is: it is outside of the right MLG tire marks!

What are the chances that the right tire punctured when hitting the lights and the marks are actually created by a flattened right tyre, also pulling the aircraft to the right?

https://data.ntsb.gov/Docket/Documen...-FINAL-Rel.pdf

Moderator

The problem is: it is outside of the right MLG tire marks!

There have been times while training a tailwheel pilot, that I've had to remind them to pull the power off after touchdown....

Drain Bamaged

By the way, if you look at figure 15 of the UAV report, it claims that there is an additional tire mark from the tail wheel.

The problem is: it is outside of the right MLG tire marks!

What are the chances that the right tire punctured when hitting the lights and the marks are actually created by a flattened right tyre, also pulling the aircraft to the right?

https://data.ntsb.gov/Docket/Documen...-FINAL-Rel.pdf

The problem is: it is outside of the right MLG tire marks!

What are the chances that the right tire punctured when hitting the lights and the marks are actually created by a flattened right tyre, also pulling the aircraft to the right?

https://data.ntsb.gov/Docket/Documen...-FINAL-Rel.pdf

I am pretty sure this tail wheel's mark outside the mains can be explained by a sideway skid of the airframe.

Think of it as two overloaded brains loosing control of an aircraft getting below vmca.

If you want to extend, they probably didn't even touch the power to go around. Rather than just left it were it was when they were initially trying to bring it to the threshold... Before getting caught by vmca (I'm almost tempted to say vmca becoming vmcg)

Join Date: Dec 2014

Location: LHBS

Posts: 281

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Just an illustration how much sideways skid this means. Apparently doable, but what seems unusual to me is the drift to the right, while turning right at the same time.

Usually vehicles tend to turn one way and drift the other way in the process. In case of a ground loop to the left, nose turns left, tail swings right, and the aircraft will tend to drift right.

Here the drift is to the same side as the turn. Someone must have tried to steer the aircraft to the left with the rudder, but instead of turning left, the aicraft continued to turn right due to the asymmetric thrust. What a huge struggle this has been....

With regards to why the high power setting, I read the testimony of the mechanic. His last memory is that he sits onto the turret, but he is not strapped in. Survivors reported that the landing on the MLG was hard and everything "flew forward". The mechanic came to his senses in between the pilot and co-pilot. In this case, his body may have accidentally hit the power levers, too.

B-17 approximate drift

Usually vehicles tend to turn one way and drift the other way in the process. In case of a ground loop to the left, nose turns left, tail swings right, and the aircraft will tend to drift right.

Here the drift is to the same side as the turn. Someone must have tried to steer the aircraft to the left with the rudder, but instead of turning left, the aicraft continued to turn right due to the asymmetric thrust. What a huge struggle this has been....

With regards to why the high power setting, I read the testimony of the mechanic. His last memory is that he sits onto the turret, but he is not strapped in. Survivors reported that the landing on the MLG was hard and everything "flew forward". The mechanic came to his senses in between the pilot and co-pilot. In this case, his body may have accidentally hit the power levers, too.

B-17 approximate drift

I finally got a chance to watch the above video. Rather damning yet somehow understandable. The predisposition to assume the fault was with engine 4 when engine 3 failed was really the primary cause - with everything else unfortunately following (wasn't that also a factor in that turboprop that crashed in Taiwan a few years back?).

I'm finding myself very conflicted. As I've noted previously, I'd flown on Nine-O-Nine about 12 years ago, and greatly valued the experience, but I'm dismayed by the lack of accountability and oversight that lead to this crash. Coincidentally I just received a donation request from the Collings Foundation.

Part of me wants to make a donation to preserve the sort of experience I received on Nine-O-Nine, but part of me is reluctant to support the apparently shoddy operations that lead to this crash...

I'm finding myself very conflicted. As I've noted previously, I'd flown on Nine-O-Nine about 12 years ago, and greatly valued the experience, but I'm dismayed by the lack of accountability and oversight that lead to this crash. Coincidentally I just received a donation request from the Collings Foundation.

Part of me wants to make a donation to preserve the sort of experience I received on Nine-O-Nine, but part of me is reluctant to support the apparently shoddy operations that lead to this crash...

Join Date: Nov 2015

Location: Paisley, Florida USA

Posts: 289

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Wow, talk about speculation on my part, that's a whole bunch of "possible", "could have", "I think", "seems", "may have" etc.

As you pointed out, a conscious decision to "go around" after all that had previously occurred on the flight makes no sense; yet, the power on three of the engines was up at impact. My question remains: "Why wasn't the power "chopped" when the airplane hit the approach lights?"

Oh, concerning the speculation on the B-17's tail wheel, it does have a locking tail wheel, like the DC-3/C-47. The NTSB Docket Report indicates that the locking mechanism was damaged sometime during the crash sequence.

Cheers,

Grog

Moderator

the B-17's tail wheel, it does have a locking tail wheel, like the DC-3/C-47

Join Date: Dec 2013

Location: Dallas

Posts: 108

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

The concept of the LHFE combined with the value of sharing the story of those proud aircraft and the accomplishments of their crews is noble. I have flown in Nine-O-Nine and other Collings Foundation aircraft, and greatly valued the experiences.

After reading the recently released NTSB docket, it's difficult to reconcile the ideals represented by the Collings Foundation's efforts and the reality of what occurred.

After reading the recently released NTSB docket, it's difficult to reconcile the ideals represented by the Collings Foundation's efforts and the reality of what occurred.

Last edited by ThreeThreeMike; 31st Dec 2020 at 17:48.

Join Date: Dec 2014

Location: LHBS

Posts: 281

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

There is one way to reconcile the conflicting feeling about this: hard work towards noble causes doesn't guarantee appropriate compliance. These are 2 totally different things.

Considering that individuals and organizations working towards noble causes are very highly respected, they tend to receive less criticism than others, leading to weaker oversight too. So the risk of going downhill in safety compliance is very very real risk.

This is a trap that so many highly respected people walk into. You do something really great and the appreciating applause completely overdominates and suppresses the tiny voices of worry or doubt.

I am sure the pilot, Mac, was a hugely respectable man, with an unparallelled wealth of knowledge and a lot of hard work towards the noble cause everyone appreciated.

But this also gave him the "untouchable" status too, with high trust and lower oversight from the Foundation and his colleagues at the Foundation, including his co-pilot and his mechanic that day.

In aviation such status is of dubious value and increases the risk of death. .

As Scott points out in his video: at 19:42: "The important lesson to learn is that this can happen to any one of us, at any time, if we aren't working on it."

I think the foundation still deserve support, but everyone who donates should point out that better oversight on the chief pilots and chief IA mechanics must be implemented and maintained. And we should remain vocal about perceived incorrect practices, lack of engine run-ups, the logic of intermediate takeoffs, missing passenger briefings. Speaking up, just culture don't go against the "noble cause". They go against practices which threaten the work towards the noble cause. A big difference to remember.

Considering that individuals and organizations working towards noble causes are very highly respected, they tend to receive less criticism than others, leading to weaker oversight too. So the risk of going downhill in safety compliance is very very real risk.

This is a trap that so many highly respected people walk into. You do something really great and the appreciating applause completely overdominates and suppresses the tiny voices of worry or doubt.

I am sure the pilot, Mac, was a hugely respectable man, with an unparallelled wealth of knowledge and a lot of hard work towards the noble cause everyone appreciated.

But this also gave him the "untouchable" status too, with high trust and lower oversight from the Foundation and his colleagues at the Foundation, including his co-pilot and his mechanic that day.

In aviation such status is of dubious value and increases the risk of death. .

As Scott points out in his video: at 19:42: "The important lesson to learn is that this can happen to any one of us, at any time, if we aren't working on it."

I think the foundation still deserve support, but everyone who donates should point out that better oversight on the chief pilots and chief IA mechanics must be implemented and maintained. And we should remain vocal about perceived incorrect practices, lack of engine run-ups, the logic of intermediate takeoffs, missing passenger briefings. Speaking up, just culture don't go against the "noble cause". They go against practices which threaten the work towards the noble cause. A big difference to remember.

Join Date: Nov 2015

Location: Paisley, Florida USA

Posts: 289

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

rnzoli;

I think that you have written an excellent description of what happens to an organization that has achieved the status of a "Sacred Cow". That organization (or person) is viewed as being above constructive criticism or even above mild comment on what could be improved. This phenomenon is not just limited to aviation enterprises.

Back in the day, when it was my job to give "constructive criticism" to various organizations/individuals, I would often be met with the philosophy of: "We've been doing it this way for years. What could happen?"

At this point I would not give any support to the Collings Foundation until it is known that their basic philosophy of complacency has been replaced "from the top down". For example, naming a nineteen year old (23 yrs. old at the time of the accident) as the Chief Pilot just because he's related to the owners is inappropriate in my book. How any Chief Pilot (of any age) can ride herd on 50 or more volunteer pilots (of varying experience/qualifications) from all across the country is beyond my comprehension.

I hope the Collings Foundation survives this; however, I have my doubts.

I could go on and on, but I won't.

Regards,

Grog

I think that you have written an excellent description of what happens to an organization that has achieved the status of a "Sacred Cow". That organization (or person) is viewed as being above constructive criticism or even above mild comment on what could be improved. This phenomenon is not just limited to aviation enterprises.

Back in the day, when it was my job to give "constructive criticism" to various organizations/individuals, I would often be met with the philosophy of: "We've been doing it this way for years. What could happen?"

At this point I would not give any support to the Collings Foundation until it is known that their basic philosophy of complacency has been replaced "from the top down". For example, naming a nineteen year old (23 yrs. old at the time of the accident) as the Chief Pilot just because he's related to the owners is inappropriate in my book. How any Chief Pilot (of any age) can ride herd on 50 or more volunteer pilots (of varying experience/qualifications) from all across the country is beyond my comprehension.

I hope the Collings Foundation survives this; however, I have my doubts.

I could go on and on, but I won't.

Regards,

Grog

Last edited by capngrog; 31st Dec 2020 at 23:04. Reason: correct misspelling

Join Date: Jun 2001

Location: Rockytop, Tennessee, USA

Posts: 5,898

Likes: 0

Received 1 Like

on

1 Post

Final NTSB Accident Report here: https://u7061146.ct.sendgrid.net/ls/...glEDEnmwS8Q-3D

WASHINGTON (April 13, 2021) ó The National Transportation Safety Board detailed in an accident report issued Tuesday the circumstances that led to the crash of a Boeing B-17G airplane that killed seven people and injured seven others.

The NTSB determined the probable cause of the accident was the pilot's failure to properly manage the airplane's configuration and airspeed following a loss of engine power. Safety issues found during this investigation were discussed during a March 23, 2021, public board meeting on Part 91 revenue passenger-carrying operations.

The Word War II-era Boeing B-17G airplane had just departed Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, Oct. 2, 2019, on a ďliving history flight experience" flight with 10 passengers when the pilot radioed controllers that the airplane was returning to the field because of an engine problem. The airplane struck approach lights, contacted the ground before reaching the runway and collided with unoccupied airport vehicles; the majority of the fuselage was consumed by a post-crash fire.

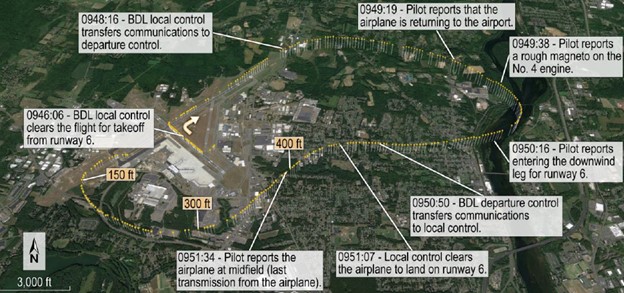

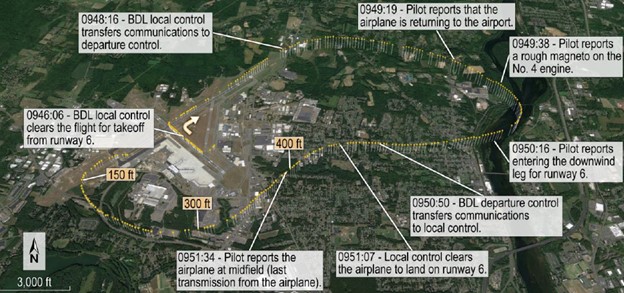

(This figure shows the airplane's flightpath on Oct. 2, 2019, between 9:46 a.m., when the airplane was cleared for takeoff, and 9:51 a.m., when one of the pilots reported the airplane was at midfield. The locations when the airplane reached 400, 300, and 150 feet above ground level are also shown. NTSB graphic overlay on Google Earth image.)

(This figure shows the airplane's flightpath on Oct. 2, 2019, between 9:46 a.m., when the airplane was cleared for takeoff, and 9:51 a.m., when one of the pilots reported the airplane was at midfield. The locations when the airplane reached 400, 300, and 150 feet above ground level are also shown. NTSB graphic overlay on Google Earth image.)

Flightpath data indicated that during the return to the airport the landing gear was extended prematurely, adding drag to an airplane that had lost some engine power. An NTSB airplane performance study showed the B-17 could likely have overflown the approach lights and landed on the runway had the pilot kept the landing gear retracted and accelerated to 120 mph until it was evident the airplane would reach the runway.

The pilot also served as the director of maintenance for the Collings Foundation, which operated the airplane, and was responsible for the airplane's maintenance while it was on tour in the United States. Investigators said the partial loss of power in two of the four engines was due to the pilot's inadequate maintenance, which contributed to the cause of the accident.

The NTSB also determined that although the Collings Foundation had a voluntary safety management system in place, it was ineffective and failed to identify and mitigate numerous hazards, including the safety issues related to the pilot's inadequate maintenance of the airplane.

The Federal Aviation Administration's oversight of the Collings Foundation safety management system was also ineffective, the NTSB said, and cited both as contributing to the accident.

The Federal Aviation Administration's inadequate oversight was discussed in the NTSB's report, Enhance Safety of Revenue Passenger-Carrying Operations Conducted Under Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91. In that report, the NTSB recommended the FAA require safety management systems for the revenue passenger-carrying operations discussed in the report, which included living history flight experience flights such as the B-17 flight.

The NTSB also issued recommendations to the FAA that would enhance the safety of revenue passenger-carrying operations conducted under Part 91, including those conducted with a living history flight experience exemption, which currently allows sightseeing tours aboard former military aircraft to be operated under less stringent safety standards than other commercial operations.

The full accident report, Impact with Terrain Short of the Runway, Boeing B-17G, Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks, Connecticut, Oct. 2, 2019, is available online at https://go.usa.gov/xHbMw.

Enhance Safety of Revenue Passenger-Carrying Operations Conducted Under Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91 is available online at https://go.usa.gov/xHbMj.

Probable Cause and Findings

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilotís failure to properly manage the airplaneís configuration and airspeed after he shut down the No. 4 engine following its partial loss of power during the initial climb. Contributing to the accident was the pilot/maintenance directorís inadequate maintenance while the airplane was on tour, which resulted in the partial loss of power to the Nos. 3 and 4 engines; the Collings Foundationís ineffective safety management system (SMS), which failed to identify and mitigate safety risks; and the Federal Aviation Administrationís inadequate oversight of the Collings Foundationís SMS.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilotís failure to properly manage the airplaneís configuration and airspeed after he shut down the No. 4 engine following its partial loss of power during the initial climb. Contributing to the accident was the pilot/maintenance directorís inadequate maintenance while the airplane was on tour, which resulted in the partial loss of power to the Nos. 3 and 4 engines; the Collings Foundationís ineffective safety management system (SMS), which failed to identify and mitigate safety risks; and the Federal Aviation Administrationís inadequate oversight of the Collings Foundationís SMS.

Pilotís Actions, Maintenance Issues, Ineffective Safety Management System and Oversight, all Contributed to Fatal Crash of Historic B-17 Airplane

4/13/2021WASHINGTON (April 13, 2021) ó The National Transportation Safety Board detailed in an accident report issued Tuesday the circumstances that led to the crash of a Boeing B-17G airplane that killed seven people and injured seven others.

The NTSB determined the probable cause of the accident was the pilot's failure to properly manage the airplane's configuration and airspeed following a loss of engine power. Safety issues found during this investigation were discussed during a March 23, 2021, public board meeting on Part 91 revenue passenger-carrying operations.

The Word War II-era Boeing B-17G airplane had just departed Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, Oct. 2, 2019, on a ďliving history flight experience" flight with 10 passengers when the pilot radioed controllers that the airplane was returning to the field because of an engine problem. The airplane struck approach lights, contacted the ground before reaching the runway and collided with unoccupied airport vehicles; the majority of the fuselage was consumed by a post-crash fire.

(This figure shows the airplane's flightpath on Oct. 2, 2019, between 9:46 a.m., when the airplane was cleared for takeoff, and 9:51 a.m., when one of the pilots reported the airplane was at midfield. The locations when the airplane reached 400, 300, and 150 feet above ground level are also shown. NTSB graphic overlay on Google Earth image.)

(This figure shows the airplane's flightpath on Oct. 2, 2019, between 9:46 a.m., when the airplane was cleared for takeoff, and 9:51 a.m., when one of the pilots reported the airplane was at midfield. The locations when the airplane reached 400, 300, and 150 feet above ground level are also shown. NTSB graphic overlay on Google Earth image.)Flightpath data indicated that during the return to the airport the landing gear was extended prematurely, adding drag to an airplane that had lost some engine power. An NTSB airplane performance study showed the B-17 could likely have overflown the approach lights and landed on the runway had the pilot kept the landing gear retracted and accelerated to 120 mph until it was evident the airplane would reach the runway.

The pilot also served as the director of maintenance for the Collings Foundation, which operated the airplane, and was responsible for the airplane's maintenance while it was on tour in the United States. Investigators said the partial loss of power in two of the four engines was due to the pilot's inadequate maintenance, which contributed to the cause of the accident.

The NTSB also determined that although the Collings Foundation had a voluntary safety management system in place, it was ineffective and failed to identify and mitigate numerous hazards, including the safety issues related to the pilot's inadequate maintenance of the airplane.

The Federal Aviation Administration's oversight of the Collings Foundation safety management system was also ineffective, the NTSB said, and cited both as contributing to the accident.

The Federal Aviation Administration's inadequate oversight was discussed in the NTSB's report, Enhance Safety of Revenue Passenger-Carrying Operations Conducted Under Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91. In that report, the NTSB recommended the FAA require safety management systems for the revenue passenger-carrying operations discussed in the report, which included living history flight experience flights such as the B-17 flight.

The NTSB also issued recommendations to the FAA that would enhance the safety of revenue passenger-carrying operations conducted under Part 91, including those conducted with a living history flight experience exemption, which currently allows sightseeing tours aboard former military aircraft to be operated under less stringent safety standards than other commercial operations.

The full accident report, Impact with Terrain Short of the Runway, Boeing B-17G, Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks, Connecticut, Oct. 2, 2019, is available online at https://go.usa.gov/xHbMw.

Enhance Safety of Revenue Passenger-Carrying Operations Conducted Under Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91 is available online at https://go.usa.gov/xHbMj.

Join Date: Nov 2015

Location: Paisley, Florida USA

Posts: 289

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

For a year or more, the severity of this accident puzzled me, and how an emergency landing that "had the runway made" turned into a fatal tragedy was not adequately addressed in the NTSB Reports. Although the airplane sustained minor damage when it struck the runway approach lights, that would have been the extent of the incident IF THE THROTTLES HAD BEEN CLOSED. When the aircraft struck the approach lights, engines Nos. 1 & 2 (left side) were operating at or near full throttle, and for some reason, nowhere addressed in the NTSB Reports, the throttles were not closed. Engine No. 4 was already feathered and Engine No.3 was ailing and not providing anything near full or even partial power.

With Engines Nos. 1 & 2 operating at high power settings, the aircraft veered sharply right and ultimately collided with a de-icing fluid (glycol) tank located on the airport property. These two engines were found to have been operating at or near full throttle when the aircraft impacted the glycol tank. The subsequent fire completed the destruction of the airplane and resulted in the deaths of those not killed at impact.

For the above reasons, this accident would just not let loose of my mind; consequently, I gave it much thought and studied all of the information available from the NTSB documents (I even read the entire Accident Docket several times). I also spoke at length with a good friend of mine (a retired FAA guy) who knew personally the B-17 pilot and was familiar with the Collings Foundation aviation operations.

Several of the posters to this thread have touched upon the possibility that the pilots' failure to wear the available shoulder harnesses could have been a factor in the failure to close the throttles, and it was pointed out that the violent swerve to the right could have pinned Mac (the PIC) against the left side of the cockpit, making reaching the throttles difficult for him ... if not impossible. Thinking about this, I realized that the co-pilot's body would have also been flung to the left during the crash sequence, quite possibly impacting the throttles, pushing all four full forward. It should be noted that the co-pilot's injuries were different than those of the PIC, in that he suffered considerable injury to his thorax, which (according to the Medical Examiner) was the cause of his death (not fire/smoke inhalation). During all of this, No.4 was caged, and No.3 was developing only minimal power at best; consequently, all of the available thrust was on the left, causing the airplane's continued swerve to the right.

After eating at me for a few weeks, I decided to call the NTSB with my theory about the movement of the co-pilot's body. I eventually was able to speak (telephone) with the Investigator In Charge (IIC), Robert Gretz and shared the theory with him. He said that he and his colleagues at the NTSB had also been puzzled as to why the throttles were not closed during the accident sequence. He said he'd take another look at the evidence and see if anything else revealed itself concerning the question of the throttles. He called back a few weeks later and said that the theory still "held water" and that something else from the wreckage seemed to support my theory. Although not included in any of the published NTSB documents concerning this accident, the No.2 throttle lever had been found bent severely to the LEFT.

Anyway, that's my theory, and the NTSB thinks that it's reasonable and that the wearing of shoulder harnesses could have reduced this accident to the level of merely a reportable incident. I don't know if any new recommendations/regulations will result from all of this; however, all we can do is wait and see. I understand that these Living History flight operations operate under a waiver, and many FAA Regulations are "relaxed" for these operations; however I assume that these operations are now "under the microscope" and changes may be coming.

With Engines Nos. 1 & 2 operating at high power settings, the aircraft veered sharply right and ultimately collided with a de-icing fluid (glycol) tank located on the airport property. These two engines were found to have been operating at or near full throttle when the aircraft impacted the glycol tank. The subsequent fire completed the destruction of the airplane and resulted in the deaths of those not killed at impact.

For the above reasons, this accident would just not let loose of my mind; consequently, I gave it much thought and studied all of the information available from the NTSB documents (I even read the entire Accident Docket several times). I also spoke at length with a good friend of mine (a retired FAA guy) who knew personally the B-17 pilot and was familiar with the Collings Foundation aviation operations.

Several of the posters to this thread have touched upon the possibility that the pilots' failure to wear the available shoulder harnesses could have been a factor in the failure to close the throttles, and it was pointed out that the violent swerve to the right could have pinned Mac (the PIC) against the left side of the cockpit, making reaching the throttles difficult for him ... if not impossible. Thinking about this, I realized that the co-pilot's body would have also been flung to the left during the crash sequence, quite possibly impacting the throttles, pushing all four full forward. It should be noted that the co-pilot's injuries were different than those of the PIC, in that he suffered considerable injury to his thorax, which (according to the Medical Examiner) was the cause of his death (not fire/smoke inhalation). During all of this, No.4 was caged, and No.3 was developing only minimal power at best; consequently, all of the available thrust was on the left, causing the airplane's continued swerve to the right.

After eating at me for a few weeks, I decided to call the NTSB with my theory about the movement of the co-pilot's body. I eventually was able to speak (telephone) with the Investigator In Charge (IIC), Robert Gretz and shared the theory with him. He said that he and his colleagues at the NTSB had also been puzzled as to why the throttles were not closed during the accident sequence. He said he'd take another look at the evidence and see if anything else revealed itself concerning the question of the throttles. He called back a few weeks later and said that the theory still "held water" and that something else from the wreckage seemed to support my theory. Although not included in any of the published NTSB documents concerning this accident, the No.2 throttle lever had been found bent severely to the LEFT.

Anyway, that's my theory, and the NTSB thinks that it's reasonable and that the wearing of shoulder harnesses could have reduced this accident to the level of merely a reportable incident. I don't know if any new recommendations/regulations will result from all of this; however, all we can do is wait and see. I understand that these Living History flight operations operate under a waiver, and many FAA Regulations are "relaxed" for these operations; however I assume that these operations are now "under the microscope" and changes may be coming.