Corsairville-The Lost Domain Of The Flying Boat

Thread Starter

Corsairville-The Lost Domain Of The Flying Boat

At the Mission to Seafarers where I do voluntary work I came across a copy of Corsairville by Graham Coster.

It is in good condition altho looks like it has sat on someones bookshelf for some years.

When I have had time to read it I am happy to pass it onto someone to read and also pass it on.

PM me if interested. I will be away for the next week.

Emeritus

It is in good condition altho looks like it has sat on someones bookshelf for some years.

When I have had time to read it I am happy to pass it onto someone to read and also pass it on.

PM me if interested. I will be away for the next week.

Emeritus

Does anybody actually know where this small town was? All of the contemporary accounts say it was on the Dungu River near Faradje but where exactly was it? I don’t think that the book mentioned above tells you

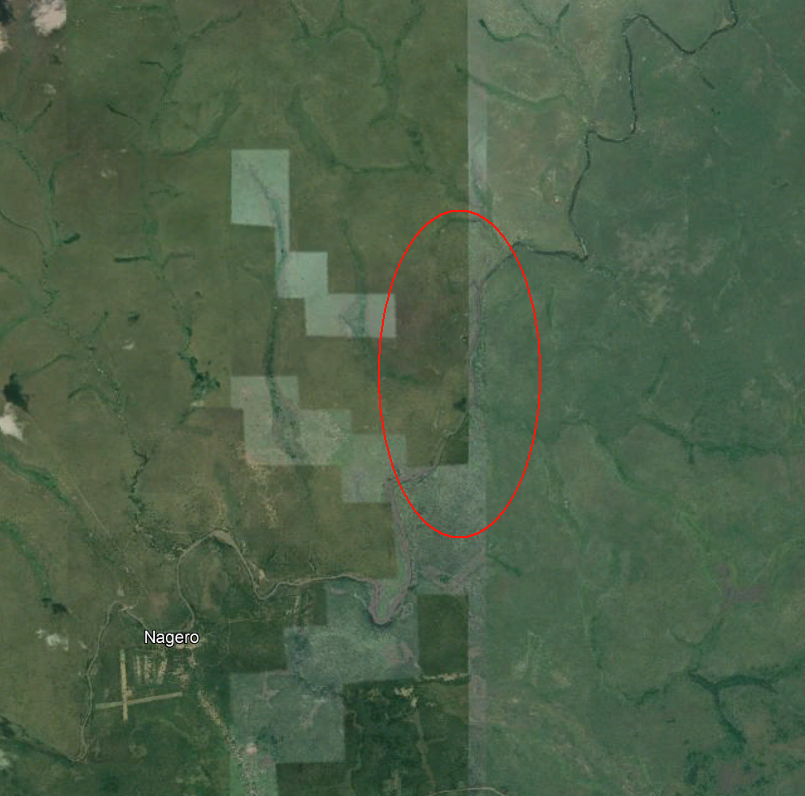

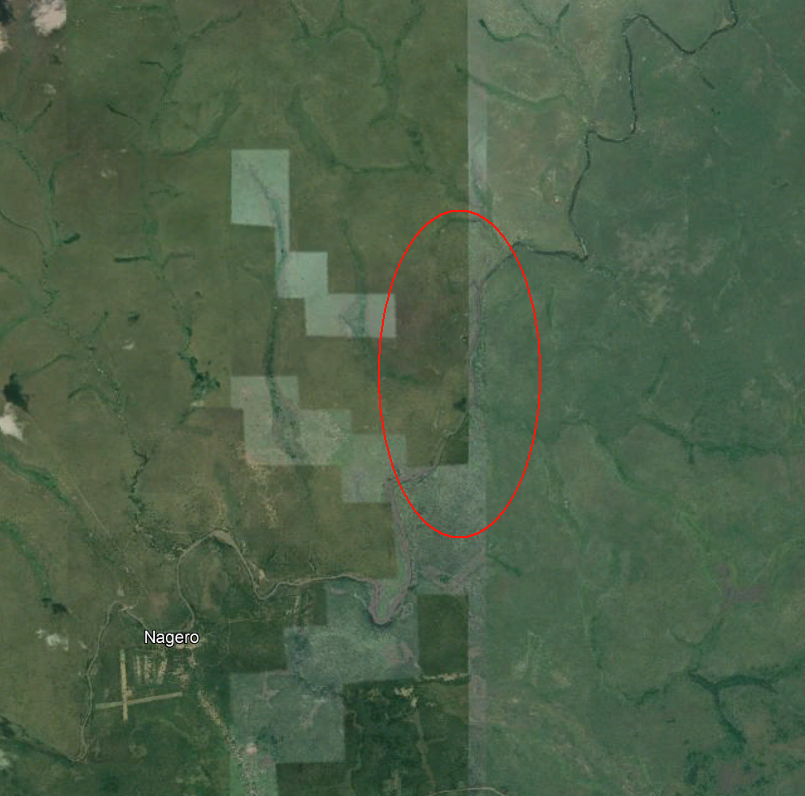

Did a search along the river from Faradje to the end of the Dungu River (at Dungu township) and could only find the Nagero National Park, which was established in the year prior to the event, and what is possibly a lodge, as signs of habitation, the only grass hut villages obvious were six miles to the east of Faradje. The aircraft was making the two hour flight from Port Bell to Juba. Article "Flight of the River Phoenix" from March 2013 issue of Aviation History by aviation author and Ppruner Stephan Wilkinson follows,

After a flying boat made a forced landing in Africa, a comedy of errors kept it jungle-bound for 10 long months.Hard to know which is worse: running out of gas over water in a landplane or doing it in a flying boat over a jungle, but in March 1939, crewmen of a four-engine Imperial Airways Short Empire flying boat found them- selves with exactly that Hobson’s choice. Utterly lost over East Africa with just 15 minutes’ fuel remaining, they fortunately found a small, remote river barely wider than the airplane’s wingspan and managed to at least land.

Thus began a little-known epic of aircraft recovery—but let’s back up a bit.

In the late 1930s, the British had developed a short-lived but effective way to stitch together their far-flung empire, much of which lay the length of Africa, plus the vast subcontinent of India and the island continent Australia. Mail, particularly, needed to move between these outliers and the home islands, so commerce and government could function. Passengers as well, but they were the icing on the air transport cake. So Imperial Airways (later to become British Overseas Airways Corporation—BOAC—and ultimately today’s British Airways) had contracted with seaplane builders Short Brothers to develop a flying boat that was roughly comparable to America’s better-known and substantially larger Pan Am Clipper, the Boeing 314.

Shorts called them Empires, but Imperial dubbed them their C-class aircraft, and each was given a name beginning with C. Our unfortunate lost boy was dubbed Corsair.

On March 14, 1939, Corsair had taken off at first light from the vast inland sea of Lake Victoria, northbound from South Africa to Southampton, England, on what was normally a five-day trip. What followed was a spectacularly inept piece of aviating, never mind that the captain in charge was Edward Alcock, younger brother of the sainted Sir John Alcock, one of the two pilots who participated in the first-ever nonstop transatlantic flight.

Soon after its second takeoff of the day, bound for Juba, in the Sudan, from a Ugandan harbor also on Lake Victoria, Alcock the younger had gone aft for a lie-down, leaving a first officer, a radio operator and an autopilot in charge. When Alcock came back two hours later, reports have it that the copilot was lounging with his feet up on the panel, Sparks had his headset casually cocked over one ear and George was doing the flying.

“So where are we, then?” Alcock asked. “Take a bearing on Juba.”

“Huh. We’ve already passed it,” said the radioman after checking the DF needle’s swing.

In fact they were flying steadily away from Juba, having for some reason headed northwest after takeoff rather than north. History has placed the blame on a direction-finding radio that was improperly replaced by technicians at their last overnight stop, but in fact the finger points straight at lazy crewmen who apparently never bothered to correlate their heading with a course line on a chart. To them, situational awareness seems to have meant knowing the way to the hotel bar.

They were supposed to land on the White Nile, a major river that should at some point have appeared under them, pointing toward their destination. But below them now was unbroken jungle and rapidly increasing fog.

For two more hours, Corsair stumbled back and forth across the void, hoping to find something recognizable. At least they spied what later turned out to be the little-known Dungu River in the Belgian Congo.

Alcock somewhat redeemed himself by putting Corsair down on the Dungu, barely wider than the boat’s wingspan, but he hit a submerged boulder on the runout, putting a 26-foot gash in the hull. With Corsair about to sink, Alcock powered the aircraft onto the steep riverbank and held it there long enough for his crew to chop a hole in the fuselage to let the 13 passengers out onto relatively dry land. (Some had been asleep, and Alcock decided neither to wake them nor to let the others know they were about to land, perhaps out of embarrassment.) Then the flying boat slid back down into the shallow, muddy river, as its waters flooded the fuselage.

Though Corsair was a bargain by jet airliner standards, a replacement aircraft would have cost the equivalent of $3.8 million in today’s dollars. But that was irrelevant. Shorts wasn’t making any more Empire boats. With the prospect of war looming, the company was then totally committed to manufacturing Stirling bombers and Sunderlands—essentially heavily militarized and uprated Empire boats for Coastal Command. Corsair needed to come home under its own power.

Shorts sent a 26-year-old engineer, Hugh Gordon, with a team of mechanics to haul Corsair ashore and patch its hull. It was an enormous job that required hundreds of native laborers and, ultimately, involved constructing a village to house the recovery team. That settlement is known to this day as Corsairville. (Gordon’s 2009 obituary in one UK newspaper reported that “Gordon and his team had to eat snake sandwiches, and Gordon remembered the local Belgian health official being carried through on a sedan chair, followed by his African mistress, who was carrying a tin kettle and naked but for a trilby hat.”)

After spending three months drilling thousands of rivet holes by hand and patching the hull, the crew refloated the flying boat. Alcock fired up Corsair and thundered off down the river.

And again hit a rock.

This time it was serious. The Dungu had passed its flood stage and was getting increasingly shallow, more a swamp than a river. Congo weather would ruin the flying boat before the water was again high enough for the twice-repaired Corsair to attempt yet another takeoff. So an Imperial Airways civil engineer, George Halliday, was sent down from Cairo to dam the Dungu and create an artificial lake.

On January 13, 1940, 10 months to the day after Corsair first force-landed, the battered boat was ready for one more try. Halliday’s dam had begun to collapse during the night, and the water level was growing dangerously low. But now Imperial had its top pilot in the left seat, Irishman John C. Kelly-Rogers. (Kelly-Rogers got all the important assignments. There’s a famous photo of Winston Churchill in the left seat of a BOAC Boeing 314, a cigar the length of a Coney Island hot dog clamped in his jaws, headset atop his balding dome and the flying boat’s enormous yoke in his hands as he makes a stab at flying the Clipper. Kelly-Rogers was the captain on that flight, from Virginia to Bermuda. He’d of course left his copilot in the right seat, having quietly ordered him to make control corrections only if the prime minister did anything dumb.)

“When we started,” Kelly-Rogers recalled, “the river was only 50 yards wide and Corsair spanned 38 yards. We took careful soundings, adjusted the load and let her go. When she started lifting, I knew somehow we were going to make it. But I don’t think anyone else did.”

In the end, Imperial Airways got its money’s worth. Refurbished, Corsair soldiered on, eventually in BOAC livery, until the big flying boat was scrapped in January 1947. It was a relic of an era that long-range landplanes and concrete runways had ended forever—but it also remains a symbol of one of the most remarkable aircraft salvage efforts ever undertaken.

Thus began a little-known epic of aircraft recovery—but let’s back up a bit.

In the late 1930s, the British had developed a short-lived but effective way to stitch together their far-flung empire, much of which lay the length of Africa, plus the vast subcontinent of India and the island continent Australia. Mail, particularly, needed to move between these outliers and the home islands, so commerce and government could function. Passengers as well, but they were the icing on the air transport cake. So Imperial Airways (later to become British Overseas Airways Corporation—BOAC—and ultimately today’s British Airways) had contracted with seaplane builders Short Brothers to develop a flying boat that was roughly comparable to America’s better-known and substantially larger Pan Am Clipper, the Boeing 314.

Shorts called them Empires, but Imperial dubbed them their C-class aircraft, and each was given a name beginning with C. Our unfortunate lost boy was dubbed Corsair.

On March 14, 1939, Corsair had taken off at first light from the vast inland sea of Lake Victoria, northbound from South Africa to Southampton, England, on what was normally a five-day trip. What followed was a spectacularly inept piece of aviating, never mind that the captain in charge was Edward Alcock, younger brother of the sainted Sir John Alcock, one of the two pilots who participated in the first-ever nonstop transatlantic flight.

Soon after its second takeoff of the day, bound for Juba, in the Sudan, from a Ugandan harbor also on Lake Victoria, Alcock the younger had gone aft for a lie-down, leaving a first officer, a radio operator and an autopilot in charge. When Alcock came back two hours later, reports have it that the copilot was lounging with his feet up on the panel, Sparks had his headset casually cocked over one ear and George was doing the flying.

“So where are we, then?” Alcock asked. “Take a bearing on Juba.”

“Huh. We’ve already passed it,” said the radioman after checking the DF needle’s swing.

In fact they were flying steadily away from Juba, having for some reason headed northwest after takeoff rather than north. History has placed the blame on a direction-finding radio that was improperly replaced by technicians at their last overnight stop, but in fact the finger points straight at lazy crewmen who apparently never bothered to correlate their heading with a course line on a chart. To them, situational awareness seems to have meant knowing the way to the hotel bar.

They were supposed to land on the White Nile, a major river that should at some point have appeared under them, pointing toward their destination. But below them now was unbroken jungle and rapidly increasing fog.

For two more hours, Corsair stumbled back and forth across the void, hoping to find something recognizable. At least they spied what later turned out to be the little-known Dungu River in the Belgian Congo.

Alcock somewhat redeemed himself by putting Corsair down on the Dungu, barely wider than the boat’s wingspan, but he hit a submerged boulder on the runout, putting a 26-foot gash in the hull. With Corsair about to sink, Alcock powered the aircraft onto the steep riverbank and held it there long enough for his crew to chop a hole in the fuselage to let the 13 passengers out onto relatively dry land. (Some had been asleep, and Alcock decided neither to wake them nor to let the others know they were about to land, perhaps out of embarrassment.) Then the flying boat slid back down into the shallow, muddy river, as its waters flooded the fuselage.

Though Corsair was a bargain by jet airliner standards, a replacement aircraft would have cost the equivalent of $3.8 million in today’s dollars. But that was irrelevant. Shorts wasn’t making any more Empire boats. With the prospect of war looming, the company was then totally committed to manufacturing Stirling bombers and Sunderlands—essentially heavily militarized and uprated Empire boats for Coastal Command. Corsair needed to come home under its own power.

Shorts sent a 26-year-old engineer, Hugh Gordon, with a team of mechanics to haul Corsair ashore and patch its hull. It was an enormous job that required hundreds of native laborers and, ultimately, involved constructing a village to house the recovery team. That settlement is known to this day as Corsairville. (Gordon’s 2009 obituary in one UK newspaper reported that “Gordon and his team had to eat snake sandwiches, and Gordon remembered the local Belgian health official being carried through on a sedan chair, followed by his African mistress, who was carrying a tin kettle and naked but for a trilby hat.”)

After spending three months drilling thousands of rivet holes by hand and patching the hull, the crew refloated the flying boat. Alcock fired up Corsair and thundered off down the river.

And again hit a rock.

This time it was serious. The Dungu had passed its flood stage and was getting increasingly shallow, more a swamp than a river. Congo weather would ruin the flying boat before the water was again high enough for the twice-repaired Corsair to attempt yet another takeoff. So an Imperial Airways civil engineer, George Halliday, was sent down from Cairo to dam the Dungu and create an artificial lake.

On January 13, 1940, 10 months to the day after Corsair first force-landed, the battered boat was ready for one more try. Halliday’s dam had begun to collapse during the night, and the water level was growing dangerously low. But now Imperial had its top pilot in the left seat, Irishman John C. Kelly-Rogers. (Kelly-Rogers got all the important assignments. There’s a famous photo of Winston Churchill in the left seat of a BOAC Boeing 314, a cigar the length of a Coney Island hot dog clamped in his jaws, headset atop his balding dome and the flying boat’s enormous yoke in his hands as he makes a stab at flying the Clipper. Kelly-Rogers was the captain on that flight, from Virginia to Bermuda. He’d of course left his copilot in the right seat, having quietly ordered him to make control corrections only if the prime minister did anything dumb.)

“When we started,” Kelly-Rogers recalled, “the river was only 50 yards wide and Corsair spanned 38 yards. We took careful soundings, adjusted the load and let her go. When she started lifting, I knew somehow we were going to make it. But I don’t think anyone else did.”

In the end, Imperial Airways got its money’s worth. Refurbished, Corsair soldiered on, eventually in BOAC livery, until the big flying boat was scrapped in January 1947. It was a relic of an era that long-range landplanes and concrete runways had ended forever—but it also remains a symbol of one of the most remarkable aircraft salvage efforts ever undertaken.

The book was reissued a few years ago with the title The Flying Boat that fell to earth. It is the original book but with a new substantial afterword, has anybody read it?Would it give a clue to the location?

The Haynes manual on the C-Class notes in a chapter on the incident that 600 yards had been made available on the river for the after repair take-off, but from the comments of the captain, it wasn't 100% straight. So it seems we're looking for a section of the river that might conceivably be around 600 yards long, at least 50 yards wide and perhaps a little banana shaped ?

Candidates close to Faradje might be the north/south stretch immediately to the west of Faradje, or perhaps the east/west section immediately to the east (although this one looks a little narrow, we don't know what trees were around back then).

Candidates close to Faradje might be the north/south stretch immediately to the west of Faradje, or perhaps the east/west section immediately to the east (although this one looks a little narrow, we don't know what trees were around back then).

"The Flying Boat That Fell To Earth" has a map that indicates that the site of the landing on the Dungu river was about 10-11miles west-north-west of Faradje, just south-west of the northern most point of the Dungu's loop in this area.

The stretch of river running noth-east to south west around 3°46'37.82"N 29°33'10.96"E looks promising.

The stretch of river running noth-east to south west around 3°46'37.82"N 29°33'10.96"E looks promising.

Further details from Graham Coster's book indicate that the Dungu river landing site chiristened 'Corsairville' was situated 6 miles overland from the village of Nagero, which lies a little over 13 miles west of Faradje.

The rather crude map (hand drawn?) in the book indicates (if the scale and orientation are accurate) that the site is approximately 13 miles from Faradje on a bearing of about 280deg. T. This map position would put the site just to the north of, but very close to Nagero - which seems to be at odds to the '6 miles from Nagero' statement above.

I suspect the '6 miles' statement to be more accurate than what I am able to infer from the map - for someone to quote that figure one could reasonably infer that it had been travelled and the distance known.

With this in mind, this is the most likely stretch of the Dungu that I think the Corsair landed on:-

I think that 6 miles the other side (west) of Nagero takes it too far from Faradje, and at too southerly a bearing.

One other interesting detail mentioned is that the dam which was constructed was 'keyed' into each bank and had a total span of some 72m (230ft) - quite a bit more than the width of the river, thus digging some way into each bank. Apparently the remains of the keyed-in sections on the river banks were still to be seen in the mid 1990's when Coster was gathering information for the book. In theory, if they've survived another 20+ years they should still be visible on Google Earth, but I've not been able to locate anything definitive up to now.

The rather crude map (hand drawn?) in the book indicates (if the scale and orientation are accurate) that the site is approximately 13 miles from Faradje on a bearing of about 280deg. T. This map position would put the site just to the north of, but very close to Nagero - which seems to be at odds to the '6 miles from Nagero' statement above.

I suspect the '6 miles' statement to be more accurate than what I am able to infer from the map - for someone to quote that figure one could reasonably infer that it had been travelled and the distance known.

With this in mind, this is the most likely stretch of the Dungu that I think the Corsair landed on:-

I think that 6 miles the other side (west) of Nagero takes it too far from Faradje, and at too southerly a bearing.

One other interesting detail mentioned is that the dam which was constructed was 'keyed' into each bank and had a total span of some 72m (230ft) - quite a bit more than the width of the river, thus digging some way into each bank. Apparently the remains of the keyed-in sections on the river banks were still to be seen in the mid 1990's when Coster was gathering information for the book. In theory, if they've survived another 20+ years they should still be visible on Google Earth, but I've not been able to locate anything definitive up to now.

Many thanks for this update. DH106. I wonder if it will be worth asking somebody in the African forum who may have more local knowledge or contacting the author via his publisher?

A sound clip exists made by one of the Imperial ground staff who travelled to the spot to evacuate the passengers. You can listen to it here- http://whitewaterlandings.co.uk/voic.../#comment-4435