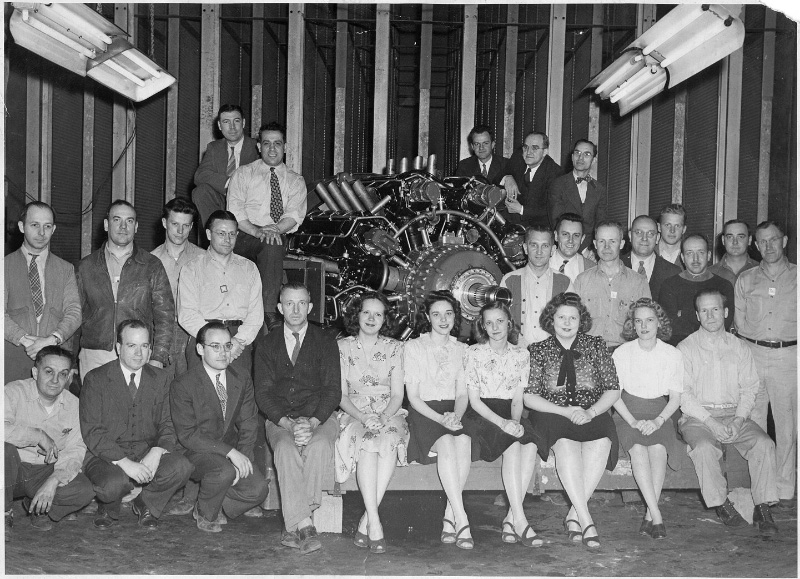

XR-7755 ENGINEERING TEAM are shown with their "baby", the giant 36 cylinder engine. Left to right in the front row are; Boris Osojnak, Tom Kennedy, Otto Shuey, Sam Fry, Robert McElhanny and Don Little. In the second row are Jack Carpenter, John Guibord, Clarence Wiegman, Charlotte Plankenhorn, Roscoe Kendig, Robert Dittmar and Paul M. McBride. In the third row are Hess Wertz, George Love, Bernard Shew, Edgar Demmien, Frank Murray, Leo Aldrich, Fred Jones, Waldo Bird and Jim McRoberts. This photograph was taken November 14, 1945. (Photo: Paul M. McBride)

This 36 cylinder engine was destined to be the largest reciprocating engine ever built. The displacement was 7,755 cubic inches. When compared to Lycoming's largest production engine in production today which displaces 720 cubic inches, it was more than 10 times larger!

Development of the XR-7755 began at Lycoming in Williamsport in the summer of 1943. With the end of World War II in 1945, the military no longer had a need for an engine of this size, and development of the XR-7755 stopped at the prototype stage.

During those years, Lycoming put together a team, under the leadership of VP Engineering Clarence Wiegman, to develop this super-size engine.

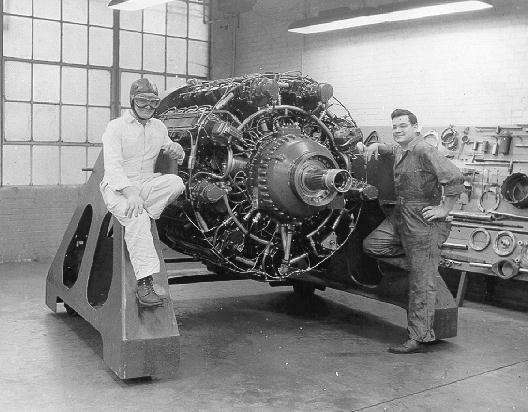

The resulting design used nine banks of four cylinders arranged around a central crankshaft to form a four-row radial engine. Unlike most multi-row radials, which splay the cylinders to allow cooling air to reach them, the R-7755 was water-cooled and so the cylinder heads were in-line under a cooling jacket. Contrast this with the Junkers Jumo 222, which looked similar from the outside but ran on a V-style cycle instead of a radial. The R-7755 was 10 ft (3 m) long, 5 ft (1.5 m) in diameter, and weighed 6,050 lb (2,740 kg). At full power it was to produce 5,000 hp (3,700 kW) at 2,600 rpm, maintaining that with a turbocharger to a critical altitude of 7,000 feet. It used 580 GPH of avgas at the 5,000 HP rating.

Each cylinder bank had a single overhead cam powering the poppet valves. The camshaft included two sets of cams, one for full takeoff power, and another for economical cruise. The pilot could select between the two settings, which would shift the camshaft along its axis to bring the other set of cams over the valve stems. Interestingly, the design mounted some of the accessories on the "front side" of the camshafts, namely two magnetos and four distributors. The seventh camshaft was not used in this fashion, its location on the front of the engine was used to feed oil to the propeller reduction gearing.

The original XR-7755-1 design drove a single propeller, but even on the largest aircraft the propeller needed to absorb the power would have been ridiculously large. This led to a minor redesign that produced the XR-7755-3, using a new propeller gearing system driving two shafts to power a set of contra-rotating props. The propeller reduction gearing also had two speed settings to allow for a greater range of operating power than adjustable props alone could deliver. Another minor modification resulted in the XR-7755-5, the only change being the replacement of carburetors with a new fuel injection system.

Operational history

The engine first started testing at 5,000 hp (3,700 kW) in 1944 with the XR-7755-3, but demonstrated terrible reliability problems. A second example was provided, as planned, to the United States Army Air Forces at Wright Field in 1946. However, by this time the Air Force had lost interest in new piston designs due to the introduction of jet engines, and the Lycoming delivery team was instructed to simply "dump it on the ground". This engine has since disappeared. The original test engine was later delivered to the Smithsonian Institution, where it was recently restored.