IT WAS

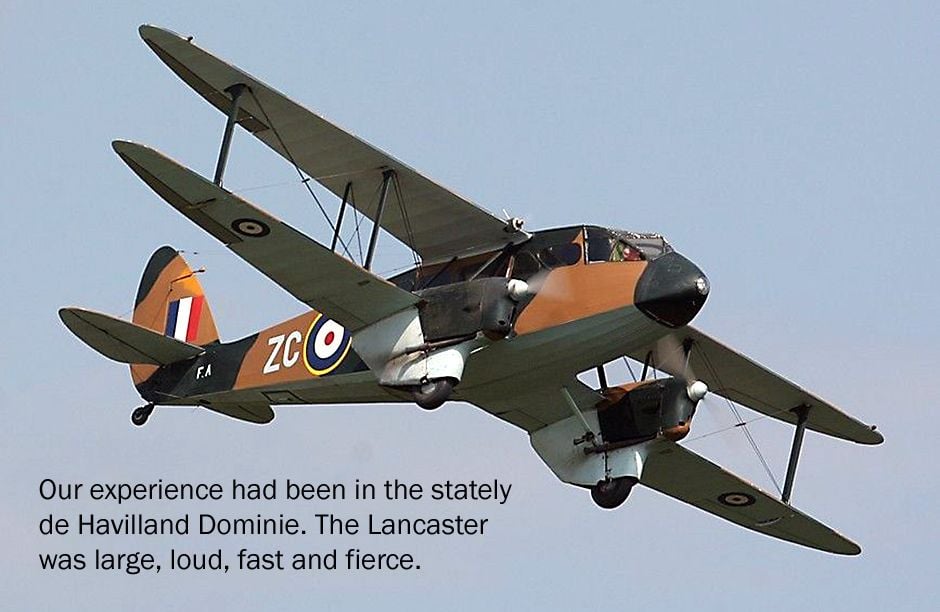

IT WAS a very exciting time. We were sent to No.1 LFS (Lancaster Finishing School) at Hemswell, north of Lincoln, to fly for 10 hours as passengers in Lancasters, and familiarise ourselves with being carried in large four-engined bombers. This was quite necessary as our air experience previously had been in the stately de Havilland Dominie (Dragon Rapide biplane) and tiny Percival Proctors. The Lancaster was large, loud, fast, and fierce. While we were there, the second front opened with D-Day on 6 June 1944.

Soon we went on to 101 Squadron at Ludford Magna on the Lincolnshire Wolds. This was a three-flight squadron, flying up to 24 Lancasters in the bomber stream, armed and loaded with bombs just like the other heavy bombers but with an extra crew member in each squadron aircraft to do the jamming.

Upon arrival the first thing was a few daysí introduction to the equipment we were to operate. It went under the codename 'ABC', which stood for Airborne Cigar; I have no idea why they named it that. It consisted of three enormous powerful transmitters covering the radio voice bands used by the Luftwaffe.

To help identify the channels to jam there was a panoramic receiver covering the same bands. The receiver scanned up and down the bands at high speed and the result of its travel was shown on a timebase calibrated across a three-inch cathode ray tube in front of the operator. If there was any traffic on the band it showed as a blip at the appropriate frequency along the line of light that was the timebase.

When a 'blip' appeared, one could immediately spot tune the receiver to it and listen to the transmission. If the language was German then it only took a moment to swing the first of the transmitters to the same frequency, press a switch and leave a powerful jamming warble there to prevent the underlying voice being heard. The other two transmitters could then be brought onto other 'blips'. If 24 aircraft were flying, spread through the bomber stream, then there were a potential 72 loud jamming transmissions blotting out the night fighters' directions.

The Germans tried all manner of devices to overcome the jamming, including having their instructions sung by Wagnerian sopranos. This was to fool our operators into thinking it was just a civilian channel and not worth jamming. I think ABC probably did a useful job, but who can say what difference it made. Anyway, it was an absorbing time for keen, fit, young men who thought only of the challenges and excitements of their task and little of the risks they were about to run.

Next step was to get "crewed up". The normal seven-man crews for Lancasters had been made up and had been flying together for months before arrival at the Squadron. We Special Duty Operators now had to tag on to established crews and it was left largely to us to find out with which pilot we, in our ignorance, might wish to fly.

Just before this process started both Keith and I were called into the squadron adjutant's office one morning and told that we had been commissioned as pilot officers. The adjutant, a kindly, ageing flight lieutenant, advised us to go to Louth, the local town, see a tailor and order an officer's uniform. We were to get the tailor to remove our sergeant's stripes and replace them with the narrow pilot officers shoulder bands on our battle-dresses. He should finally provide us with an officer's hat! The adjutant gave us vouchers to hand to the tailor to assure him he would be paid! We were told to move our kit from the NCOs' quarters to officers' accommodation and the adjutant would see us in the Officers' Mess at 6pm to buy us each a beer.

I had imagined that becoming an officer would include some kind of OTU or training course to instruct us what sort of behaviour might be expected of us. Not so, not for newly commissioned aircrew on a bomber station in Lincolnshire in the middle of 1944. What is described in the previous paragraph is all that happened.

Looking back I can see that all the things we were experiencing at this frenetic time were tremendous shocks to our systems. They left us ill equipped to take the apocalyptic decisions we were about to make and which, as it happened, would decide whether we lived or died.