Originally Posted by

WE Branch Fanatic

For the sake of completeness, and to offer some defence of those criticised by those with the benefit of forty years of hindsight:

From Chapter 4 - 'South to Ascension' - of One Hundred Days by Admiral Sandy Woodward..

Basically, it was necessary to work the campaign out backwards, starting with the chilling thought that the Task Group would be falling apart by mid to late June without proper maintenance and with winter setting in. This did not allow for enemy action, since reinforcements and replacements from the UK should cover that. So we were obliged to make a crucial assumption - that the land battle would be over by the end of June, and preferably a good two weeks before that. The retaking of Port Stanley was obviously the 'critical path' for military planning, whatever the politicians might decide. On that basis, therefore, if the land forces were to be given reasonable time to do their stuff, we had to put them on the beaches by 25 May. That would give them about a month to establish the beach head, break out, march to the likely main positions around Stanley and defeat the Argentinians on the ground. During this time we would provide then with all the artillery and air support we could; hopefully enough for their needs. And throughout the operation we had to keep the sea and sky sufficiently clear to allow reasonably safe passage to and from the beach head, with stores, people, ammunition, food and fuel - by ship and by helicopter.

I duly pinned my cardboard dates on the overall calendar. It was a mobile 'bar chart' of the kind dearly loved by all planners. We continued to work backwards: we must be here by X, there by Y, have established an airstrip by Z. In the end I remember one piece of cardboard proving to be the key to most of our problems. Upon this was written the name 'Intrepid', the sister ship to Fearless. We had to have her in the South Atlantic as a standby amphibious headquarters ship, just in case Fearless, should be sunk. The problem was that in late March, Intrepid had been 'destored' and put in reserve, as an early step in Mr Nott's grand plan for reductions in the Navy. To get her South, we had to reverse this complicated process. As far as we could estimate, there was no way she could get down to the Falklands, properly prepared, before 16 May. She would be the last ship to arrive, the last piece in the jigsaw, so all the timings depended on her.

There will still unknowns like the weather, enemy action, accidents, political initiatives and settlements. But here was a hard plan, give or take about ten days. It was a military plan from which there could be no political diversions if we were to fight and win. The 'landing window' extended from 16 May (the first day Intrepid could arrive) until 25 May. Inside that time we had to have most of land forces ashore. And, to be in good shape by mid May, we were going to have to get the Special Forces ashore for reconnaissance very soon. It was now 17 April, and the bar chart showed us we could enter the Exclusion Zone by 1 May if we pressed on hard. South Georgia should be clear by then, and sixteen days should suffice for the reconnaissance phase.

The amphibians would be able to wait behind, stay in hard training at Ascension, re-stow their equipment in better order, and set off ten days from now, prepared to go ashore any time after arrival, wherever reece suggested was the best place. This part of the plan had the added merit of allowing the Battle Group the option of entering the Exclusion Zone without the encumbrance of the amphibious ships. The thought of taking on the Argentinian with a large convoy of amphibians and merchant ships requiring simultaneous protection - all wallowing about at twelve knots - had ben a considerable source of worry to me. Now we had the option to fight without one hand tied between our backs, which was a good idea, really. Rather better than going all that ways as escorts to a large convoy.

In other words, the plan was to fight the Argentines to establish sea control and enough air superiority for an amphibious assault, before the amphibious ships and ground forces got there. Similarly NATO war planning routed most transatlantic reinforcement and resupply convoys on a Southern latitude which would take them from the Caribbean to near the coast of Portugal, while NATO naval forces, including the carriers, fought in the region of the GIUK gap and the Norwegian Sea, to stop a break out and attacks

en masse.

Although I cannot understand his opposition to the F-35 (all versions), at least Sharkey Ward has never denied the importance of a balanced surface fleet, unlike duty idiots like Lewis Page.This is from Sea Harrier Over The Falklands:

There were essentially three elements of naval warfare which had to be controlled and directed from the Ops Room: Above the Surface (Air), On the Surface, and Under the Surface (Anti submarine). These were very much interbred and interdependent, thanks to the variety of modem weapons available to the fleet and the sophistication of the modern threat. It was therefore no easy task to collect and collate the information from all the ship's sensor (including aircraft sensors and information from other platforms) and present them to the Command in an easily digestible fashion. All friendly units in each element had to be continuously plotted and information from the separate levels of defence recorded, so that in extremitis the Command could judge priority and take the appropriate action.

Defence in depth had become the war fighting philosophy of the day. Against the air threat, the outer layer of defence could be air to air and surface to air systems provided by a third party and deployed some point between the source of the threat and the fleet at sea. In the South Atlantic there was no such layer available and the Task Group had to rely on its organic defensive weapon platforms.

The out layer of air and surface defence was the Sea Harrier on Combat Air Patrol. Whenever the threat assessment made air attack highly possible, or probable, then CAP aircraft would be stationed up threat to deter and/or engage the attackers. (Should a surface attack be predicted then the SHAR would be dispatched over the horizon to search for the enemy units.) Air defence radar pickets (warships fitted with suitable sensors and weapon systems) would also be stationed up threat, but inside the CAP stations, to provide information to the CAP and the Carrier Group itself. These pickets would be armed with a variety of surface to air weapons and represented a second line of defence. The next layer of defence was the the medium or long range surface to air ship borne missile system. Sea Dart fulfilled this role for the Group. Attackers or their air to surface missiles that managed to penetrate through the outer layers of defence would then face the next designer system - the Short Range or Point Defence Missile Systems such as Sea Wolf. And, as a last ditch defence (on the hard kill side), high rate of fire, radar directed guns such as Phalanx fitted bill. Soft kill options, such as jamming and chaff were also an important integral part of the air defence in depth scenario.

If one analyses the probabilities of engagement and kill of each of the layers of defence, and calculates the overall probabilities of engagement and kill of the cumulative system, it is easy to demonstrate mathematically and in practice that money spent on defence in depth is far better than spending the same amount on a single 'all singing, all dancing' weapon system. The latter can never be perfect or 100% efficient and if it has weaknesses, which it surely will, the threat will be certain to capitalise on these deficiencies and circumvent the system. The separate layers of defence in depth each act as a deterrent to an enemy, and each are capable of causing attrition to attacking forces.

It is the Commander Task Group's job to ensure that where possible he does not place his force in a position that denies that force the full benefit of its defence in depth systems, whether by geographical location or by misuse of a particular asset or layer.

The under surface threat had to be approached in the same manner as the air threat, using third party resources, long range sensors such as Towed Array Sonar, ASW frigates as a screen between the threat and the group, anti submarine helicopters on the screen and at other locations around the group, and last but not least sonars fitted to the ships in the main body. Each of the anti submarine platforms must be capable of not only locating the threat submarine but also of prosecuting it with appropriate weapons. And with the submarine threat being ever present and very difficult to detect, the various level of defence have to be working at 100 per cent efficiency for twenty four hours a day when in a threat zone*.

There were, of course, no third parties of any description providing defence for the Task Force in the South Atlantic; no Nimrods, no air defence fighter barriers, and no shore based Airborne Early Warning (AEW) aircraft#.

*Technological developments since 1982 have changed things and increased the range at which submarines can be detected, with the advent of things such as low frequency active sonar. The longer range comes at the expense of resolution, which is where the helicopter with dipping sonar really comes into its own.

#The Sea Harrier, and the CVS, was expected to operate in the GIUK Gap and Norwegian Sea, with Tomcats from USN carriers and two squadrons of RAF Phantoms (dedicated to maritime air defence) providing the bulk of the air defence, supported by AEW. The Nimrods sent South in 1982 were mostly used to ASuW roles.

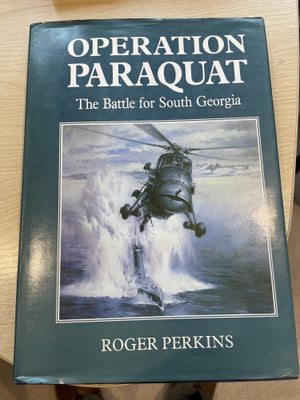

As for naval helicopters versus submarines, these pages are about the engagement of the ARA Santa Fe:

I am not sure why these have turned out so small.

Some highlights:

Parry describes the role of an ASW helicopter Observer:'Essentially you are there to navigate the aircraft, to plan tactics, and to operate the weapon systems. There are other things of course, such as communications with ships and other helicopters....'

It sounds like what US Navy Naval Flight Officers do in fixed wing aircraft! The Tactical Coordinator in the US Navy's S-3 Viking did that, so why not someone in the back of the MH-60R as that has taken over as the main USN shipborne ASW aircraft?

As for the value of radar: I suggested to Ian that we should Switch on the radar for a single one second sweep, One was all I could make - any more would have told an enemy skipper that he was under surveillance from the air and he could plot his course and speed.I illuminated and immediately picked up five or six traces in the area ahead and out to sea. I was expecting this because I had been marking on my chart several icebergs which we had been plotting for several days and which all had their individual names - Fred, Charlie and so forth. But there was just one blip - about files miles due North of Barff Point - which showed up where it shouldn't have been. It was faint, but I instinctively felt it was our submarine. I reported it to Ian and give him the range and bearing. Shortly afterwards, in a very cool time, he reported 'submarine ahead'.

Yet the USN SH-3 had no radar. The Royal Navy though that radar was essential for the ASW role - as was the Observer to coordinate and control things.

Dipping sonar as a deterrent: Stanley the went into a hover whilst Fitzgerald dunked the sonar transceiver. With signals already being received in the helicopter it would be much easier to keep track of his movements is the submarine commander did decide to submerge. The Wessex continued the sonar watch until Parry heard that the second helicopter had arrived over the target.

As for the tactical coordination role: Chris Parry had not been able to talk by radio to the two Endurance

Wasps, but he had been coordinating the movements of the two Lynx from HMS Brilliant and the Wasp from HMS Plymouth.

HMS Brilliant, with her modern sonar systems, had only just arrived in the area and it was unlikely that the Santa Fe would have been in her sonar range. The older sonars fitted to Antrim and Plymouth would have been pretty short ranged, so it was a helicopter only affair. Later on in the conflict, prolonged ASW hunts took place with frigates, including the two Type 22s, acting in conjunction with ASW Sea Kings from Hermes and Invincible.That was how Cold War ASW would be, with friendly submarines and MPA also contributing. The development of modern towed array sonars gives the surface force a considerably greater range of detection now, and potentially means that you can cope with less ASW helicopters, however the role of the dipping sonar in conjunction with the towed array is essential.

All very interesting WEBF, but as all of this concerns events of 40 (yes FORTY) years ago surely your post should be in "Aviation History and Nostalgia?"