This is the final instalment of our inspiring story of Sqn Ldr Ian McRitchie, DFC, and is told by his daughter,

Anne Joyce McRitchie.

WHEN my father arrived back in Australia, his focus had to be on making a success of his new business with Ken Watts and supporting his family. He did not have the financial resources to pursue his love of flying. However, in my late twenties I had a boyfriend who owned a light aircraft so I started learning to fly at Moorabbin airport on the outskirts of Melbourne. I was transferred to Sydney for work before I qualified for my licence, but my interest had renewed my father’s love of flying and at 55 he took it up again.

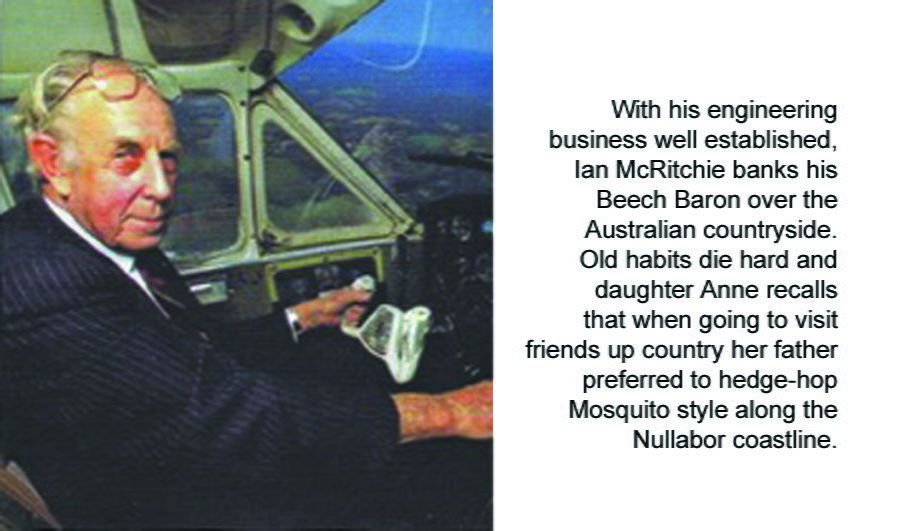

He went on to own a variety of aircraft including a Beech Baron twin, and for many years my father and mother enjoyed weekend flights into country areas, parking the plane, hopping onto a motorbike, and whizzing into town for lunch before the flight home. He often flew the 600 miles north to Arkaroola, in the spectacular, rugged mountains of the Flinders Ranges in South Australia's remote Outback, to visit his good friend Dr. Reg Spriggs, who ran Arkaroola Station.

His other favourite destination was Western Australia where he went to visit his mentor from his RAF days Sir Basil Embry, who after retiring from the RAF in February 1956 had bought a largely undeveloped farming property in the south west of Western Australia. He also acquired land at Cape Riche, east of Albany, and moved there in the late 1960s. I sometimes accompanied Ian and Joyce on their visits to Cape Riche where we were warmly welcomed by the Embry family.

Flying with my father was not for the faint-hearted! Whenever I flew with him to Western Australia he insisted on flying along the Australian Bight at cliff height, Mosquito style skimming the waves while he pointed out rock formations in the cliffs of the Nullabor. When he had the plane on auto-pilot he would often appear to drop off to sleep which could be very unsettling for the passengers although he would immediately spring to attention at the slightest change in the movement or sound of the plane.

One day I was flying with my parents out of a small aerodrome near Melbourne. My mother was sitting in the front seat with me alone in the back. I was rather unwell at the time having come to Melbourne to recover from heavy bouts of chemotherapy and radiotherapy after surgery for cancer.

Suddenly my father told my mother to change places with me so that I was sitting at the dual controls. Once this manoeuvre had been successfully carried out, he told me to fly the plane along the valley we were in. Of course I did not have my licence, was recovering from medical treatment and it was several years since I had piloted a plane. Just climbing into the front seat exhausted me.

However I did my father’s bidding after he explained that there appeared to be a fault with the landing gear and he wanted to study the Operations Manual! The result was that he had to land not knowing whether the undercarriage was down or not. Of course with his flying skill it was a perfect landing and fortunately the wheels were locked down despite the warning light.

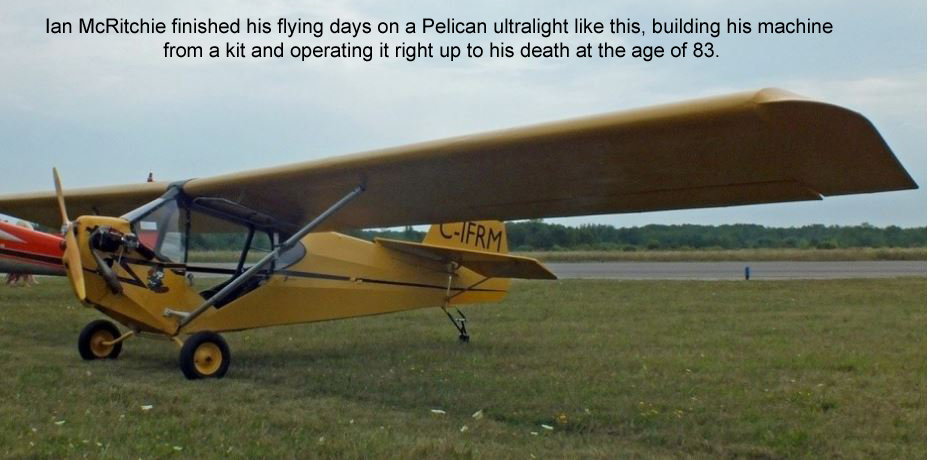

When Dad felt that he could no longer qualify to fly on medical grounds he switched to an ultralight, which he was still flying in his eighties – there was no medical examination or age limitation to fly an ultralight. My father of course was not content with any old ultralight so he and his good friend Bert Flood searched the world for the best performing machine available. They settled on an Ultravia Pelican, which was designed by Jean Rene Lepage and produced in Canada in kit form for amateur construction. My father built his own Pelican and spent many pleasurable hours in it, even flying to Arkaroola for the weekend.

Another long-term hobby was motorbike racing. After touching down in Arkaroola, Dad would take to the bush tracks with my mother riding pillion – two 80 year olds on a motorcycle exploring the countryside they loved so much. When he died there was still a motorbike stored at Arkaroola.

After the war, my father was told that he probably would not live much past his sixties as a result of his war injuries. Not one to give up without a fight, he lived until 83, having had prostate cancer for several years beforehand. He was still active up to a few months before he passed away peacefully in a Melbourne hospital on 29 January 1998.

Dad’s funeral was a big event attended by hundreds of mourners. His friends had arranged for a piper playing ‘Scottish Soldier’ to lead in the coffin while several aircraft made a flypast.

Former flight lieutenant John Lyndquist spoke glowingly of Sqn Ldr McRitchie’s deeds when they were fellow prisoners-of-war. He said my father had single-handedly boosted morale and supplies for the Allied prisoners through secret raids on German stores. “He helped make our lives slightly more bearable,” John Lyndquist said. “He fought our battles for a tiny bit more food, any warmth that might be going”.

Flying friend Bob Rowe said my father liked anything that could fly, and any challenge. “If Ian could have grown wings, he would have”, he said. Emeritus Professor Endersbee give the funeral oration, concluding with these words: “Ian McRitchie was courageous, purposeful and optimistic, industrious, adventurous and fearless. He encouraged these qualities in others. He was a loving husband, father and grandfather”.

For myself, I recalled my brave, skilful and loving father as a spirit that soared. And that’s how I shall always remember him.