Boris and bilateral security assurances: Sweden and Finland

I would possibly not be 100% as harsh as you but in a general direction I share your doubts. I would not consider them nearly as reliable as most other NATO members. Turkey has its own territorial/area of influence Agenda. And you can see this in several conflicts in Near/Middle East up to Armenia/Azerbaidschan. NATO has been a vehicle for them to aquire Top Notch Equipment and having its back covered while stirring the pot in the region.

(Come on, man: if we supported one for Bosniaks and Kosovars, how about a little love for the Kurds, eh?)

I would occasionally refer to the war in Iraq as "Operation Kurdish Freedom" and was only partly joking. Alas, it didn't work out that way.

"I would not consider them nearly as reliable as most other NATO members."

historically the Turks have fought the Russians far more than any other country in NATO

historically the Turks have fought the Russians far more than any other country in NATO

Ecce Homo! Loquitur...

They have indeed - which is why the joined NATO and the other members would respond to an Article call if they were attacked again.

The doubts are as to their reliability as an ally if another member came under attack.

How whole hearts would Erdogan be in response, for example, to an attack on Lithuania?

The doubts are as to their reliability as an ally if another member came under attack.

How whole hearts would Erdogan be in response, for example, to an attack on Lithuania?

The thing that gets me about all these PKK guys in Sweden and Finland is the chances are high that they passed through Turkey to get there. I feel Turkey is going to become increasingly problematic as it feels its position becomes more important (which it may well be), and their internal capabilities grow, which they are.

Ecce Homo! Loquitur...

Report dared the 4th, so meeting is this week.

https://www.politico.eu/article/nato...s-in-brussels/

NATO chief to meet with Finnish, Swedish, Turkish officials in Brussels

NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg will hold talks with officials from Sweden, Finland and Turkey in Brussels next week to discuss Ankara’s reservations about the two Nordic countries’ bids to join the Western military alliance.

In a visit to Washington this week, Stoltenberg said he would convene officials from all three countries in Brussels “in the coming days … to ensure that we make progress on the applications of Finland and Sweden to join NATO,” adding that both countries were “ready to sit down and to address” Turkey’s concerns.

That meeting is set to take place in NATO’s Brussels headquarters next week, according to the Associated Press….

https://www.politico.eu/article/nato...s-in-brussels/

NATO chief to meet with Finnish, Swedish, Turkish officials in Brussels

NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg will hold talks with officials from Sweden, Finland and Turkey in Brussels next week to discuss Ankara’s reservations about the two Nordic countries’ bids to join the Western military alliance.

In a visit to Washington this week, Stoltenberg said he would convene officials from all three countries in Brussels “in the coming days … to ensure that we make progress on the applications of Finland and Sweden to join NATO,” adding that both countries were “ready to sit down and to address” Turkey’s concerns.

That meeting is set to take place in NATO’s Brussels headquarters next week, according to the Associated Press….

On the other hand, why would anyone want to Join NATO? Maybe NATO is beyond its expiry date. This isn't me, an American, throwing shade at NATO, this is a Brit:

Edward Lucas is a nonresident fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, a Liberal Democratic candidate for the British Parliament, a former senior editor at The Economist, and the author, most recently, of Cyberphobia: Identity, Trust, Security and the Internet. Twitter: @edwardlucas

On the other hand, for the Finns and Swedes, maybe joining NATO is the best worst option.

Edward Lucas is a nonresident fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, a Liberal Democratic candidate for the British Parliament, a former senior editor at The Economist, and the author, most recently, of Cyberphobia: Identity, Trust, Security and the Internet. Twitter: @edwardlucas

NATO Is Out of Shape and Out of Date

With the bloc’s unity over Ukraine showing cracks, NATO needs an overhaul.

By Edward Lucas, a nonresident fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis.

Is NATO brain-dead or back in business? Less than three years ago, French President Emmanuel Macron famously diagnosed “the brain death of NATO.” Rhetoric aside, his point was fair at the time: Europe’s dearth of strategic thinking combined with the unpredictability of U.S. policy under then-President Donald Trump spelled serious trouble for the Cold War-era alliance.

Now, all talk is of NATO’s revival and resurgence. Russia’s war on Ukraine has given an urgent new relevance to the bloc’s core mission of territorial defense. NATO members appear to have found a new unity of purpose, supplying Ukraine with weapons, reassessing the threat from Russia, hiking defense budgets, and bolstering the security of the alliance’s eastern frontier. But the “honeymoon,” in the words of Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis, was brief. As the war drags on, strains are showing, and the alliance is still shaky.

It’s true that NATO has come a long way. Only 14 years ago, the alliance’s top-secret threat assessment body, MC 161, was explicitly prohibited by its political masters from even considering any military danger from Russia in its scenarios. The pressure came not only from notorious Russia-huggers such as Germany but also from the United States, which was eager to keep east-west ties friendly. The Kremlin, the conventional wisdom insisted, was a partner, not an enemy. As a result, NATO’s most vulnerable members—Poland and the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—remained second-class allies. They were in the bloc, but only on paper. There were no significant outside forces on their territory, and the alliance expressly refrained from making contingency plans to reinforce or even defend them in the event of attack. Poland demanded such plans and was told that they could be drawn up to defend the country against an attack by Belarus—but not by Russia.

Since Russia’s first attack on Ukraine in 2014, NATO plans and deployments have become more serious. There are 1,000-strong tripwire forces in the three Baltic states and a larger U.S. force in Poland. Since the start of the invasion in February, that presence has increased sharply. Moreover, two of the most advanced smaller military powers in Europe, Finland and Sweden, are banging on the alliance’s door. Assuming objections from Turkey can been smoothed out, they will be members by year’s end. That will fundamentally change the military geography of northeastern Europe.

Still more important is the stiffening of spines among the members. Trump’s much publicized distaste for NATO was based, in part, on the European members’ chronic underspending. At one point, the exasperated U.S. leader even tried to present a bill to his German counterpart, Chancellor Angela Merkel. Now, defense spending is rising across the alliance. That makes NATO an easier sell in Washington, especially as the case for U.S. engagement in European security is bolstered by the war in Ukraine.

Scholzen is a German neologism for “dither,” while makronic in Polish (and its equivalent in Ukrainian) can be roughly translated as “vacuous grandstanding while doing nothing.”

Germany, the most notorious laggard, is suddenly splurging money on its decrepit armed forces—tanks that can’t trundle, ships that can’t go to sea, and soldiers who exercise with broomsticks instead of guns. It has agreed to meet NATO’s defense spending benchmark of 2 percent of GDP, set in 2006 and largely ignored thereafter. The latest country to announce a big hike in defense spending is Spain, currently lagging at barely 1 percent of GDP. The prime minister announced that this will double by 2024. That sets the scene nicely for the NATO summit in the Spanish capital later this month.

Yet look a little more closely, and the picture is far less rosy. Notwithstanding its apparent unity of purpose since the start of Russia’s war, NATO looks out of shape and out of date. In the run-up to their summit, the allies have been furiously haggling over the language in their new strategic concept, which will frame the alliance’s mission for the coming years and will be unveiled in Madrid. What will it say about Russia? About China? What sacrifices and risks are the member states really willing to accept? Are they willing to pool sovereignty in order to streamline decision-making?

Nothing in recent weeks suggests that these questions will get clear answers. For starters, the 30-strong alliance is unwieldy. In military terms, only a handful of members matter—above all, the United States—but in political terms, even little Luxembourg and Iceland get a voice. Worse, the political divides are huge.

Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is a semi-authoritarian state that flirts with Russia and fumes at what it considers European meddling over human rights. Hungary under Prime Minister Viktor Orban is taking a different but downward path, fusing wealth and power into a new system of control at home and undermining U.S. and European attempts to put pressure on Russia and China.

Macron’s relentless posturing and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s foot-dragging create constant obstacles and distractions.

The two leader’s weaknesses, on glorious display since the start of the war, have already enriched the language: Scholzen is a German neologism for “dither,” while makronic in Polish (and its equivalent in Ukrainian) can be roughly translated as “vacuous grandstanding while doing nothing.”

Macron and Scholz corrode decision-making with their foibles and thus place a big question mark over the alliance’s credibility and cohesion. Any threat or provocation from Russia is unlikely to be clear or conveniently timed. More likely it will be something deliberately ambiguous, such as a Russian drone that “accidentally” strays onto the territory of a front-line state and hits a target. Some countries would favor a tough response. Others would fear escalation and want dialogue. Still others would take the ambiguity as a convenient excuse to do nothing. Would the 30—soon to be 32—national representatives in the North Atlantic Council, the alliance’s deliberative body, really make a speedy and tough decision on how to react? More likely, some of them would plead for delay, diplomacy, and compromise. Those actually facing the possibility of attack would be far more hawkish, preferring a sharp military confrontation to even the smallest Russian victory. “Not one inch, not one soul,” a senior military figure from one of the Baltic states, speaking anonymously, told me. “We have seen what they did in Ukraine.”

The political weaknesses are matched by military ones. By far the most important country in the alliance is the United States. The U.S. security guarantee to Europe—with its threat of devastating conventional and, if necessary, nuclear response to any attack—is the cornerstone of the alliance. “All for one and one for all” sounds fine, but nobody in the Kremlin will tremble at the thought of Spanish, Dutch, or Canadian displeasure. Yet the result of this is a colossal dependence on U.S. capabilities, ranging from ammunition and spare parts (of which European countries’ stockpiles are notoriously skinny) to military transports that move forces quickly and efficiently over long distances. Even if Europe’s new defense spending plans materialize, they will not change the fact that only U.S. armed forces can move with the scale and speed necessary to defend territory from a country like Russia.

Conversely, the countries that most need defending—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—are the least able to bear the burden themselves. They need advanced weapons, particularly for air and missile defense, that they cannot afford themselves. The thin neck of land along the Polish-Lithuanian border, the so-called Suwalki Gap, is particularly vulnerable to attack from Russia’s militarized Kaliningrad exclave and Belarus, from which Russia attacked Ukraine. Poland and Lithuania both want a big U.S. military presence—either a permanent base or a persistent rotation of forces—to safeguard this strategic chokepoint.

Yet NATO command structures and planning do not fully reflect the imbalance of forces between the United States and Europe. They rely on the fiction that the European allies are more or less equal partners. Even military lightweights need to have important-sounding jobs and installations, making the North Atlantic Council the military version of a parliament dividing out the pork.

The resulting command structure is like a tangled pile of spaghetti. In the Baltic region alone, NATO has several multinational headquarters, one divisional headquarters split between Latvia and Denmark, another divisional headquarters in Poland, and a corps headquarters at a different location in Poland. Overall responsibility for the defense of Europe is divided between three Joint Forces Command headquarters in Naples, Italy; Brunssum, the Netherlands; and Norfolk, Virginia. But the top U.S. military commander in Europe, Air Force Gen. Tod Wolters, is based at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe in Mons, Belgium. A maritime strategy for the Baltic Sea region has yet to be decided—which is just as well, because NATO has yet to create a naval headquarters for the region. Nor has the alliance drawn up real military plans for the reinforcement and defense of its northeastern members, let alone decided who would actually provide the forces and equipment in order to make them credible. Military mobility is meant to be the responsibility of Joint Support and Enabling Command, headquartered in Ulm, Germany, and originally set up as part of the European Union’s own defense policy.

Europe is, in theory, big and rich enough to manage its own defense—but its persistent political weakness prevents that.

A further problem is exercises: NATO does not conduct fully realistic, large-scale rehearsals of how it would respond to a Russian attack. One problem is that these are costly and disruptive. Another is that they expose the huge weaknesses of some NATO members, which can cope with a carefully scripted exercise but lack the ability to improvise. A third reason is the fear, in some countries, that practicing war-fighting would be provocative. Also lacking are detailed plans for fighting a war against Russia, covering such issues as reinforcing of front-line states, countering a Russian attack, regaining any temporarily occupied territory, and—most of all—dealing with a nuclear or other escalation. As a result, nobody is quite sure how anything would work in a crisis. Instead, another assumption reigns: that in a crisis, the United States would take over and do the heavy lifting on all fronts—logistics, intelligence, and combat.

To be fair, NATO is working on these problems, and all of them are fixable. But that does not mean that they are anywhere near being fixed. Wishful thinking remains the alliance’s besetting sin.

Worse, NATO is unprepared for the changing nature of modern warfare. Russia’s old-style assault on Ukraine is all too familiar. But the artillery bombardments and missile strikes that are grinding down Ukraine’s defenses are only part of the Kremlin’s arsenal. Its most effective weapons are nonmilitary: subversion, diplomatic divide-and-rule tactics, economic coercion, corruption, and propaganda. The most burning current example of nonmilitary warfare is Russia’s weaponizing of hunger. By blocking Ukraine’s grain exports, Russia has raised the specter of famine over millions of people, including in volatile and fragile countries in North Africa and the Middle East. Mass starvation is not just a humanitarian catastrophe, but its consequences include political unrest and mass migration, a direct threat to Europe. Yet NATO is ill-equipped to deal with this. It cannot mandate more economical use of grain—for example, by feeding less to livestock and stopping grain’s conversion to fuel. It has no food stockpiles to release to a hungry world. It cannot build new railways to ship Ukrainian grain through other routes. Nor can it insure merchant vessels that might—for a price—be willing to run Russia’s Black Sea blockade. NATO has little in-house expertise in countering Russian disinformation and almost zero influence in African and other countries susceptible to Kremlin narratives blaming the West for the food shortages that are already starting now.

NATO could acquire these capabilities. Or it could regain them: During the Cold War, the alliance had an economic warfare division and ran a program called the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls to prevent the Soviet bloc from acquiring sensitive technologies. But in the strategic timeout that followed the collapse of the Soviet bloc, these agencies and their skill sets shriveled and died.

But as with NATO’s military shortcomings, identifying the problems is not the same as solving them.

And given the bloc’s unwieldy structure and issues with key members, it might be wise to lower expectations about NATO returning to Cold War levels of consistent readiness and effectiveness. A more realistic vision for the alliance would be to treat it as a framework for the most capable and threat-aware members to form coalitions of the willing. These groupings already exist: The British-led Joint Expeditionary Force, for example, is a 10-country framework for military cooperation, chiefly aimed at enabling very rapid deployments to the Nordic-Baltic region in the event of a crisis. France has a similar venture, the European Intervention Initiative. The five Nordic states have their own military club, called the Nordic Defence Cooperation, while Poland has close bilateral ties with Lithuania. A similar network of bilateral and multilateral ties would greatly strengthen the alliance’s floundering presence in the Black Sea and other regions, including North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. These groupings would not supplant NATO but improve action and interoperability on top of the alliance’s established structures and mechanisms.

The difficult and underlying question here is the role of the United States. Europe is, in theory, big and rich enough to manage its own defense. But its persistent political weakness prevents that. The paradox is that only U.S. involvement makes NATO credible—yet overdependence on the United States also undermines the alliance’s credibility, while stoking resentment in France and elsewhere. The task for Washington is to encourage European allies to shoulder more of the burden and start thinking strategically again, even as it retains the superpower involvement that gives the alliance its decisive military edge. That is entirely doable. But don’t expect it to happen in Madrid—or anytime soon.

Now, all talk is of NATO’s revival and resurgence. Russia’s war on Ukraine has given an urgent new relevance to the bloc’s core mission of territorial defense. NATO members appear to have found a new unity of purpose, supplying Ukraine with weapons, reassessing the threat from Russia, hiking defense budgets, and bolstering the security of the alliance’s eastern frontier. But the “honeymoon,” in the words of Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis, was brief. As the war drags on, strains are showing, and the alliance is still shaky.

It’s true that NATO has come a long way. Only 14 years ago, the alliance’s top-secret threat assessment body, MC 161, was explicitly prohibited by its political masters from even considering any military danger from Russia in its scenarios. The pressure came not only from notorious Russia-huggers such as Germany but also from the United States, which was eager to keep east-west ties friendly. The Kremlin, the conventional wisdom insisted, was a partner, not an enemy. As a result, NATO’s most vulnerable members—Poland and the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—remained second-class allies. They were in the bloc, but only on paper. There were no significant outside forces on their territory, and the alliance expressly refrained from making contingency plans to reinforce or even defend them in the event of attack. Poland demanded such plans and was told that they could be drawn up to defend the country against an attack by Belarus—but not by Russia.

Since Russia’s first attack on Ukraine in 2014, NATO plans and deployments have become more serious. There are 1,000-strong tripwire forces in the three Baltic states and a larger U.S. force in Poland. Since the start of the invasion in February, that presence has increased sharply. Moreover, two of the most advanced smaller military powers in Europe, Finland and Sweden, are banging on the alliance’s door. Assuming objections from Turkey can been smoothed out, they will be members by year’s end. That will fundamentally change the military geography of northeastern Europe.

Still more important is the stiffening of spines among the members. Trump’s much publicized distaste for NATO was based, in part, on the European members’ chronic underspending. At one point, the exasperated U.S. leader even tried to present a bill to his German counterpart, Chancellor Angela Merkel. Now, defense spending is rising across the alliance. That makes NATO an easier sell in Washington, especially as the case for U.S. engagement in European security is bolstered by the war in Ukraine.

Scholzen is a German neologism for “dither,” while makronic in Polish (and its equivalent in Ukrainian) can be roughly translated as “vacuous grandstanding while doing nothing.”

Germany, the most notorious laggard, is suddenly splurging money on its decrepit armed forces—tanks that can’t trundle, ships that can’t go to sea, and soldiers who exercise with broomsticks instead of guns. It has agreed to meet NATO’s defense spending benchmark of 2 percent of GDP, set in 2006 and largely ignored thereafter. The latest country to announce a big hike in defense spending is Spain, currently lagging at barely 1 percent of GDP. The prime minister announced that this will double by 2024. That sets the scene nicely for the NATO summit in the Spanish capital later this month.

Yet look a little more closely, and the picture is far less rosy. Notwithstanding its apparent unity of purpose since the start of Russia’s war, NATO looks out of shape and out of date. In the run-up to their summit, the allies have been furiously haggling over the language in their new strategic concept, which will frame the alliance’s mission for the coming years and will be unveiled in Madrid. What will it say about Russia? About China? What sacrifices and risks are the member states really willing to accept? Are they willing to pool sovereignty in order to streamline decision-making?

Nothing in recent weeks suggests that these questions will get clear answers. For starters, the 30-strong alliance is unwieldy. In military terms, only a handful of members matter—above all, the United States—but in political terms, even little Luxembourg and Iceland get a voice. Worse, the political divides are huge.

Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is a semi-authoritarian state that flirts with Russia and fumes at what it considers European meddling over human rights. Hungary under Prime Minister Viktor Orban is taking a different but downward path, fusing wealth and power into a new system of control at home and undermining U.S. and European attempts to put pressure on Russia and China.

Macron’s relentless posturing and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s foot-dragging create constant obstacles and distractions.

The two leader’s weaknesses, on glorious display since the start of the war, have already enriched the language: Scholzen is a German neologism for “dither,” while makronic in Polish (and its equivalent in Ukrainian) can be roughly translated as “vacuous grandstanding while doing nothing.”

Macron and Scholz corrode decision-making with their foibles and thus place a big question mark over the alliance’s credibility and cohesion. Any threat or provocation from Russia is unlikely to be clear or conveniently timed. More likely it will be something deliberately ambiguous, such as a Russian drone that “accidentally” strays onto the territory of a front-line state and hits a target. Some countries would favor a tough response. Others would fear escalation and want dialogue. Still others would take the ambiguity as a convenient excuse to do nothing. Would the 30—soon to be 32—national representatives in the North Atlantic Council, the alliance’s deliberative body, really make a speedy and tough decision on how to react? More likely, some of them would plead for delay, diplomacy, and compromise. Those actually facing the possibility of attack would be far more hawkish, preferring a sharp military confrontation to even the smallest Russian victory. “Not one inch, not one soul,” a senior military figure from one of the Baltic states, speaking anonymously, told me. “We have seen what they did in Ukraine.”

The political weaknesses are matched by military ones. By far the most important country in the alliance is the United States. The U.S. security guarantee to Europe—with its threat of devastating conventional and, if necessary, nuclear response to any attack—is the cornerstone of the alliance. “All for one and one for all” sounds fine, but nobody in the Kremlin will tremble at the thought of Spanish, Dutch, or Canadian displeasure. Yet the result of this is a colossal dependence on U.S. capabilities, ranging from ammunition and spare parts (of which European countries’ stockpiles are notoriously skinny) to military transports that move forces quickly and efficiently over long distances. Even if Europe’s new defense spending plans materialize, they will not change the fact that only U.S. armed forces can move with the scale and speed necessary to defend territory from a country like Russia.

Conversely, the countries that most need defending—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—are the least able to bear the burden themselves. They need advanced weapons, particularly for air and missile defense, that they cannot afford themselves. The thin neck of land along the Polish-Lithuanian border, the so-called Suwalki Gap, is particularly vulnerable to attack from Russia’s militarized Kaliningrad exclave and Belarus, from which Russia attacked Ukraine. Poland and Lithuania both want a big U.S. military presence—either a permanent base or a persistent rotation of forces—to safeguard this strategic chokepoint.

Yet NATO command structures and planning do not fully reflect the imbalance of forces between the United States and Europe. They rely on the fiction that the European allies are more or less equal partners. Even military lightweights need to have important-sounding jobs and installations, making the North Atlantic Council the military version of a parliament dividing out the pork.

The resulting command structure is like a tangled pile of spaghetti. In the Baltic region alone, NATO has several multinational headquarters, one divisional headquarters split between Latvia and Denmark, another divisional headquarters in Poland, and a corps headquarters at a different location in Poland. Overall responsibility for the defense of Europe is divided between three Joint Forces Command headquarters in Naples, Italy; Brunssum, the Netherlands; and Norfolk, Virginia. But the top U.S. military commander in Europe, Air Force Gen. Tod Wolters, is based at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe in Mons, Belgium. A maritime strategy for the Baltic Sea region has yet to be decided—which is just as well, because NATO has yet to create a naval headquarters for the region. Nor has the alliance drawn up real military plans for the reinforcement and defense of its northeastern members, let alone decided who would actually provide the forces and equipment in order to make them credible. Military mobility is meant to be the responsibility of Joint Support and Enabling Command, headquartered in Ulm, Germany, and originally set up as part of the European Union’s own defense policy.

Europe is, in theory, big and rich enough to manage its own defense—but its persistent political weakness prevents that.

A further problem is exercises: NATO does not conduct fully realistic, large-scale rehearsals of how it would respond to a Russian attack. One problem is that these are costly and disruptive. Another is that they expose the huge weaknesses of some NATO members, which can cope with a carefully scripted exercise but lack the ability to improvise. A third reason is the fear, in some countries, that practicing war-fighting would be provocative. Also lacking are detailed plans for fighting a war against Russia, covering such issues as reinforcing of front-line states, countering a Russian attack, regaining any temporarily occupied territory, and—most of all—dealing with a nuclear or other escalation. As a result, nobody is quite sure how anything would work in a crisis. Instead, another assumption reigns: that in a crisis, the United States would take over and do the heavy lifting on all fronts—logistics, intelligence, and combat.

To be fair, NATO is working on these problems, and all of them are fixable. But that does not mean that they are anywhere near being fixed. Wishful thinking remains the alliance’s besetting sin.

Worse, NATO is unprepared for the changing nature of modern warfare. Russia’s old-style assault on Ukraine is all too familiar. But the artillery bombardments and missile strikes that are grinding down Ukraine’s defenses are only part of the Kremlin’s arsenal. Its most effective weapons are nonmilitary: subversion, diplomatic divide-and-rule tactics, economic coercion, corruption, and propaganda. The most burning current example of nonmilitary warfare is Russia’s weaponizing of hunger. By blocking Ukraine’s grain exports, Russia has raised the specter of famine over millions of people, including in volatile and fragile countries in North Africa and the Middle East. Mass starvation is not just a humanitarian catastrophe, but its consequences include political unrest and mass migration, a direct threat to Europe. Yet NATO is ill-equipped to deal with this. It cannot mandate more economical use of grain—for example, by feeding less to livestock and stopping grain’s conversion to fuel. It has no food stockpiles to release to a hungry world. It cannot build new railways to ship Ukrainian grain through other routes. Nor can it insure merchant vessels that might—for a price—be willing to run Russia’s Black Sea blockade. NATO has little in-house expertise in countering Russian disinformation and almost zero influence in African and other countries susceptible to Kremlin narratives blaming the West for the food shortages that are already starting now.

NATO could acquire these capabilities. Or it could regain them: During the Cold War, the alliance had an economic warfare division and ran a program called the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls to prevent the Soviet bloc from acquiring sensitive technologies. But in the strategic timeout that followed the collapse of the Soviet bloc, these agencies and their skill sets shriveled and died.

But as with NATO’s military shortcomings, identifying the problems is not the same as solving them.

And given the bloc’s unwieldy structure and issues with key members, it might be wise to lower expectations about NATO returning to Cold War levels of consistent readiness and effectiveness. A more realistic vision for the alliance would be to treat it as a framework for the most capable and threat-aware members to form coalitions of the willing. These groupings already exist: The British-led Joint Expeditionary Force, for example, is a 10-country framework for military cooperation, chiefly aimed at enabling very rapid deployments to the Nordic-Baltic region in the event of a crisis. France has a similar venture, the European Intervention Initiative. The five Nordic states have their own military club, called the Nordic Defence Cooperation, while Poland has close bilateral ties with Lithuania. A similar network of bilateral and multilateral ties would greatly strengthen the alliance’s floundering presence in the Black Sea and other regions, including North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. These groupings would not supplant NATO but improve action and interoperability on top of the alliance’s established structures and mechanisms.

The difficult and underlying question here is the role of the United States. Europe is, in theory, big and rich enough to manage its own defense. But its persistent political weakness prevents that. The paradox is that only U.S. involvement makes NATO credible—yet overdependence on the United States also undermines the alliance’s credibility, while stoking resentment in France and elsewhere. The task for Washington is to encourage European allies to shoulder more of the burden and start thinking strategically again, even as it retains the superpower involvement that gives the alliance its decisive military edge. That is entirely doable. But don’t expect it to happen in Madrid—or anytime soon.

On the other hand, why would anyone want to Join NATO? Maybe NATO is beyond its expiry date. This isn't me, an American, throwing shade at NATO, this is a Brit:

Edward Lucas is a nonresident fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, a Liberal Democratic candidate for the British Parliament, a former senior editor at The Economist, and the author, most recently, of Cyberphobia: Identity, Trust, Security and the Internet. Twitter: @edwardlucas

Edward Lucas is a nonresident fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, a Liberal Democratic candidate for the British Parliament, a former senior editor at The Economist, and the author, most recently, of Cyberphobia: Identity, Trust, Security and the Internet. Twitter: @edwardlucas

NATO Is Out of Shape and Out of Date

With the bloc’s unity over Ukraine showing cracks, NATO needs an overhaul.

By Edward Lucas, a nonresident fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis. On the other hand, for the Finns and Swedes, maybe joining NATO is the best worst option.So Russia has a free hand to discuss allowing grain shipments and blame Kiev for any holdups. Am only surprised they have not offered Mariupol as a grain terminal afaik.

My understanding is that grain shipments from Odessa are currently blocked because Ukraine has mined the channel to prevent any Russian naval attack.

So Russia has a free hand to discuss allowing grain shipments and blame Kiev for any holdups. Am only surprised they have not offered Mariupol as a grain terminal afaik.

So Russia has a free hand to discuss allowing grain shipments and blame Kiev for any holdups. Am only surprised they have not offered Mariupol as a grain terminal afaik.

My understanding is that grain shipments from Odessa are currently blocked because Ukraine has mined the channel to prevent any Russian naval attack.

So Russia has a free hand to discuss allowing grain shipments and blame Kiev for any holdups. Am only surprised they have not offered Mariupol as a grain terminal afaik.

So Russia has a free hand to discuss allowing grain shipments and blame Kiev for any holdups. Am only surprised they have not offered Mariupol as a grain terminal afaik.

- avoids mines/mine clearing;

- provides global food supply stability (kind of);

- add same trade of grain from Russia to countries facing famine;

- UN convoy escort through to dardanelles.

As for NATO being past it's use by date, the structure has issues, but the need remains. In 1949, it evolved out of the threat that the USSR was perceived to be to Europe, and the insanity of the UNSC PM status. That was a shambles from the start, and was probably the best of a bad set of choices at that time, but it led to the need for NATO, which circumvented the UNSC PM impasse.

Dealing with an aggressive and paranoid neighbour who has no regard for collateral damage and any rules of law or ethics needs collective defense to provide a measure of restraint. The problem in Ukraine today is that Obama had zero interest in foreign affairs, even when the consequences of Russias action in 2014 in Crimea and the east of Ukraine that could destabilise the world that he was a prominent leader. When Russia shot down MH-17, nothing was done... The risk to the rest of the world just from the interference with grain is real, and still the UN merely wrings its hands. NATO has a vested interest in having a war on someone else's backyard, that is simply god housekeeping.

Ukraine is legally entitled to mine their own waters to deny aggressor nations. It is illegal to mine other countries waters, or international waters.

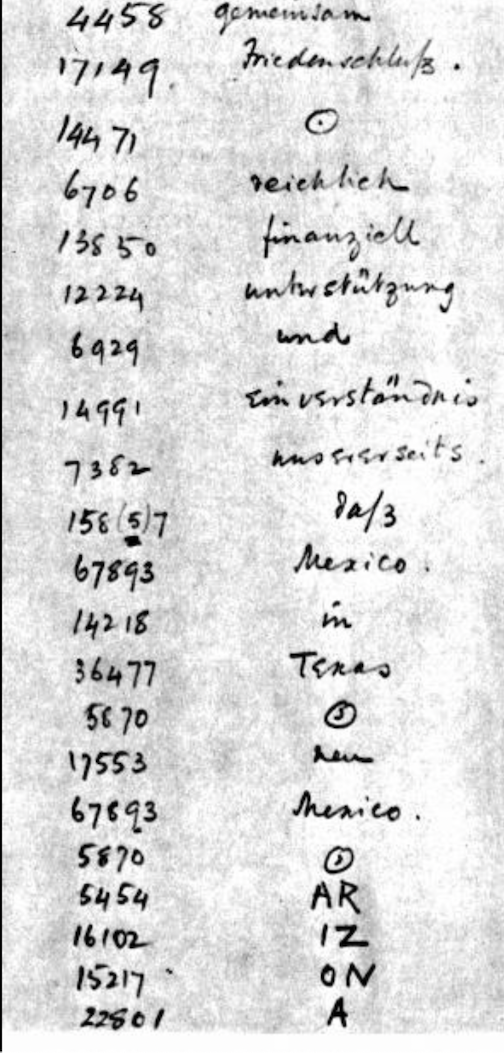

At some point in the future the whole sordid back office actions of all of the countries involved will come into to light, "Lux en tenebris" like this little bit of nostalgia from January, 1917:

Zimmermann telegram presumably.

Highlights the perils of poor quality cipher systems.

Admiral Yamamoto would concur.

Highlights the perils of poor quality cipher systems.

Admiral Yamamoto would concur.

Last edited by T28B; 10th Jun 2022 at 02:23. Reason: no need to replicate the whole post

No, Turkey is not part of the EU, it is not party to the sanctions, and has no obligation to observe any. Just like Chinese airlines are merrily doing the trans-siberian route to Europe.

The EU only prohibits Russian (and Belorussian) airlines from entering its airspace, and Russia is banning all EU airlines in return. All other airlines can come and go as they please as log as they have flight plans approved on both sides.

The EU only prohibits Russian (and Belorussian) airlines from entering its airspace, and Russia is banning all EU airlines in return. All other airlines can come and go as they please as log as they have flight plans approved on both sides.

Turkey´s NATO inclusion has basically only been to help the US meddle in ME affairs AFAIK.

Just out, Turkey has agreed going onward with the FIN and SWE applications to join NATO. To be seen how fast this track will be as some of the other NATO countries have alreadu agreed on it in their respective parliaments eg Estonia and Norway.

Let Putin put that in his pipe and smoke it.

And the ante gets raised, again.

He has a follow on post that includes two more points:

5. Deploy 2 additional Navy destroyers to Spain, bringing total from 4 to 6

6. Deploy "additional" air defense to Germany, Italy

6. Deploy "additional" air defense to Germany, Italy

Last edited by Lonewolf_50; 29th Jun 2022 at 17:52.

Join Date: Feb 2006

Location: Hanging off the end of a thread

Posts: 32,819

Received 2,795 Likes

on

1,190 Posts

Yup, his speech is in the Ukraine thread