RAE Farnborough - steeped in history

Join Date: Oct 2003

Location: Canberra Australia

Posts: 1,300

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Farnborough and ETPS Memoirs continued.

There were lots of visits to aircraft and engine manufacturing plants during the year (1955). These were always of great interest, permitting us to see the latest in technology. Solid state electronics were just starting to have an impact on designs and rapid advances were also taking place with the jet engine. The capability for an aircraft to sustain level flight at supersonic speed was not far off.

We lost one of our course members in May. Major Vickory Zarr of the Egyptian air force had been flying a Hunter Mk1 at high altitude and was returning to Farnborough through the usual low cloud and reduced visibility of the area. He had been talked down by GCA, had broken through the cloud cover and, as he reduced speed on short final, the windshield iced/misted over.

The foreign pilots with little or no previous jet experience all had trouble appreciating the voracious thirst of the jets and were often declaring emergencies over fuel shortages. So, on this occasion, Vickory did not have enough fuel for a go round. But he tried anyway. Some of us had our attention drawn to the situation when that Hunter's engine was spooled up to full power at which point it began to be starved of fuel. The engine was intermittently getting fuel and its staccato bursts of noise interspersed with silence were made graphic by great bursts of flame from the jet pipe as raw fuel pumped through unlit burner cans.

The pilot tried to turn tightly onto one of Farnborough's cross runways and while pulling in a descending turn bled off too much speed. The aircraft stalled to crash within the airfield environs just short of and to one side of the intended runway. It did not burn as there was little or no fuel remaining. Vickory's remains were taken back to Egypt for a state funeral, considering his high family and air force status.

Routine test flying training exercises continued but there were always many startling occurrences happening around us to keep the adrenalin flowing. There was also much social activity with parties at Tutors' houses or functions in the Mess. Saturday night in the Mess was nearly always a party night, well attended by students and their wives and friends.

Various past graduates of ETPS would come back to the school for the odd refresher flight in one or other of the school's aircraft. ETPS must have had an allocation of hours for this purpose and such flights seemed to be handled on an ad hoc basis.

Such was the general approach to test flying during those days that it was considered highly desirable that as many pilots as possible, get experience in as many aircraft as possible with a minimum of prior formal conversion. This approach did much to evolve standard requirements for aircraft design and handling in an era when aircraft were developing at a very rapid rate. The constrained restrictions imposed on present generation test pilots arise from a much slower rate of development and an enormous increase in capital costs of aircraft and equipment.

So it was that one day we had an RN Captain fly off in one of our Seahawks. He flew some aerobatics and during the recovery from a loop experienced a terrific bang as a goodly portion of the left side of the cockpit disappeared. He was left with little control over engine power with only a portion of the throttle linkage remaining and was only just able to limp back to Farnborough. He had not seen any other aircraft in the vicinity of the incident but presumed that he had been involved in a mid air collision. The story soon pieced together. A report was made by the pilot of a Hunter who had been flying straight and level at the time that another aircraft had plunged down on his aircraft striking it on the side of the front fuselage and taking out some of his right wing leading edge.

On the side of the Hunter's fuselage was a clear impression of a mirror image of the triangular red sign painted on the sides of aircraft cockpits having ejection seats - "Danger Ejection Seat". This had transfered from the Seahawk to the Hunter during the collision. It became an interesting exercise to subsequently use two models of the aircraft involved to attempt to reproduce the precise sequence of movement of the two aircraft as they became enmeshed for that split second of time. That both aircraft and their pilots survived is indeed remarkable.

At about this time, ETPS took delivery of a B2 Canberra No 867 which had just come through a major overhaul with English Electric at Warton. It was flown into Farnborough by one of the tutors. It was a normal practice then for the TPS engineers to do an acceptance inspection. The senior engineer was meticulous which was as well in that we all placed abnormal reliance on the reliability of the aircraft he and his team maintained and serviced.

Part of his inspection involved climbing through a hatch beneath the rear fuselage to examine the rudder and elevator control push-pull rods which ran along the left side of the fuselage through bearings at about 4 feet intervals. The rods connected directly with the flying controls in the cockpit. They were made from alloy tubing about 1 inch in diameter. The engineer discovered some metal particles scattered down the side of the fuselage in the vicinity of one of the bearings. He initially thought that one of the bearings may have seized and this may have been the source of the metal particles.

On the ground, the mass balances of the Canberra elevator controls caused the elevators to rise to their upper stops so that the control column was always fully back. The engineer used a piece of cord to tie the control column forward so that he could then inspect the complete run of the control rods. On climbing back into the rear fuselage, he was appalled to find that one of the elevator rods had been cut almost right through. The saw cut had been made so that it would be concealed by a bearing with the controls in their normal ground position.

All hell broke loose. Following an initial ETPS investigation, the police and Scotland Yard commenced a vigorous investigation at the English Electric plant at Wharton.

Some months previously, the wiring looms in the main electronics equipment bay of a Canberra being overhauled at Wharton had been extensively cut by someone using wire cutters. The culprit had not been found. Examination of work records showed that three workmen had worked on both aircraft during the periods in question. Close questioning eventually brought forth a confession by one fitter to both acts of sabotage.

Prior to the sabotage, the culprit had been working on night shifts for which there was an extra pay loading. He was transferred against his wishes to day shifts and decided to take out his resentment by deliberately damaging aircraft on which he was working. He was arrested, charged with sabotage and sentenced to life imprisonment.

I have always taken great care with pre-flight inspections ever since and it was not the last case of sabotage to cross my path.

Next installment I go flying an ETPS glider again - this time with Bill Bedford. I seemed to always have an exciting/terrifying time with someone else doing the glider flying.

There were lots of visits to aircraft and engine manufacturing plants during the year (1955). These were always of great interest, permitting us to see the latest in technology. Solid state electronics were just starting to have an impact on designs and rapid advances were also taking place with the jet engine. The capability for an aircraft to sustain level flight at supersonic speed was not far off.

We lost one of our course members in May. Major Vickory Zarr of the Egyptian air force had been flying a Hunter Mk1 at high altitude and was returning to Farnborough through the usual low cloud and reduced visibility of the area. He had been talked down by GCA, had broken through the cloud cover and, as he reduced speed on short final, the windshield iced/misted over.

The foreign pilots with little or no previous jet experience all had trouble appreciating the voracious thirst of the jets and were often declaring emergencies over fuel shortages. So, on this occasion, Vickory did not have enough fuel for a go round. But he tried anyway. Some of us had our attention drawn to the situation when that Hunter's engine was spooled up to full power at which point it began to be starved of fuel. The engine was intermittently getting fuel and its staccato bursts of noise interspersed with silence were made graphic by great bursts of flame from the jet pipe as raw fuel pumped through unlit burner cans.

The pilot tried to turn tightly onto one of Farnborough's cross runways and while pulling in a descending turn bled off too much speed. The aircraft stalled to crash within the airfield environs just short of and to one side of the intended runway. It did not burn as there was little or no fuel remaining. Vickory's remains were taken back to Egypt for a state funeral, considering his high family and air force status.

Routine test flying training exercises continued but there were always many startling occurrences happening around us to keep the adrenalin flowing. There was also much social activity with parties at Tutors' houses or functions in the Mess. Saturday night in the Mess was nearly always a party night, well attended by students and their wives and friends.

Various past graduates of ETPS would come back to the school for the odd refresher flight in one or other of the school's aircraft. ETPS must have had an allocation of hours for this purpose and such flights seemed to be handled on an ad hoc basis.

Such was the general approach to test flying during those days that it was considered highly desirable that as many pilots as possible, get experience in as many aircraft as possible with a minimum of prior formal conversion. This approach did much to evolve standard requirements for aircraft design and handling in an era when aircraft were developing at a very rapid rate. The constrained restrictions imposed on present generation test pilots arise from a much slower rate of development and an enormous increase in capital costs of aircraft and equipment.

So it was that one day we had an RN Captain fly off in one of our Seahawks. He flew some aerobatics and during the recovery from a loop experienced a terrific bang as a goodly portion of the left side of the cockpit disappeared. He was left with little control over engine power with only a portion of the throttle linkage remaining and was only just able to limp back to Farnborough. He had not seen any other aircraft in the vicinity of the incident but presumed that he had been involved in a mid air collision. The story soon pieced together. A report was made by the pilot of a Hunter who had been flying straight and level at the time that another aircraft had plunged down on his aircraft striking it on the side of the front fuselage and taking out some of his right wing leading edge.

On the side of the Hunter's fuselage was a clear impression of a mirror image of the triangular red sign painted on the sides of aircraft cockpits having ejection seats - "Danger Ejection Seat". This had transfered from the Seahawk to the Hunter during the collision. It became an interesting exercise to subsequently use two models of the aircraft involved to attempt to reproduce the precise sequence of movement of the two aircraft as they became enmeshed for that split second of time. That both aircraft and their pilots survived is indeed remarkable.

At about this time, ETPS took delivery of a B2 Canberra No 867 which had just come through a major overhaul with English Electric at Warton. It was flown into Farnborough by one of the tutors. It was a normal practice then for the TPS engineers to do an acceptance inspection. The senior engineer was meticulous which was as well in that we all placed abnormal reliance on the reliability of the aircraft he and his team maintained and serviced.

Part of his inspection involved climbing through a hatch beneath the rear fuselage to examine the rudder and elevator control push-pull rods which ran along the left side of the fuselage through bearings at about 4 feet intervals. The rods connected directly with the flying controls in the cockpit. They were made from alloy tubing about 1 inch in diameter. The engineer discovered some metal particles scattered down the side of the fuselage in the vicinity of one of the bearings. He initially thought that one of the bearings may have seized and this may have been the source of the metal particles.

On the ground, the mass balances of the Canberra elevator controls caused the elevators to rise to their upper stops so that the control column was always fully back. The engineer used a piece of cord to tie the control column forward so that he could then inspect the complete run of the control rods. On climbing back into the rear fuselage, he was appalled to find that one of the elevator rods had been cut almost right through. The saw cut had been made so that it would be concealed by a bearing with the controls in their normal ground position.

All hell broke loose. Following an initial ETPS investigation, the police and Scotland Yard commenced a vigorous investigation at the English Electric plant at Wharton.

Some months previously, the wiring looms in the main electronics equipment bay of a Canberra being overhauled at Wharton had been extensively cut by someone using wire cutters. The culprit had not been found. Examination of work records showed that three workmen had worked on both aircraft during the periods in question. Close questioning eventually brought forth a confession by one fitter to both acts of sabotage.

Prior to the sabotage, the culprit had been working on night shifts for which there was an extra pay loading. He was transferred against his wishes to day shifts and decided to take out his resentment by deliberately damaging aircraft on which he was working. He was arrested, charged with sabotage and sentenced to life imprisonment.

I have always taken great care with pre-flight inspections ever since and it was not the last case of sabotage to cross my path.

Next installment I go flying an ETPS glider again - this time with Bill Bedford. I seemed to always have an exciting/terrifying time with someone else doing the glider flying.

Milt,

Wonderful tales; thank you. Oh that we could escape from today's risk averse culture and return to your time at ETPS when a pilot's experience and ability was respected and not regulated!

Best regards.

Wonderful tales; thank you. Oh that we could escape from today's risk averse culture and return to your time at ETPS when a pilot's experience and ability was respected and not regulated!

Best regards.

Join Date: Oct 2003

Location: Canberra Australia

Posts: 1,300

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

More memories of Farnborough.

Memoirs continued.

Unfortunately LOMCEVAK those days are gone forever.

One Saturday afternoon at Farnborough I found myself sitting in the right seat of the ETPS Sedburg glider with Bill Bedford, the Harrier test pilot, in the left seat. Bill, a former ETPS tutor, was an enthusiastic glider pilot and at the time held several British gliding records for height and distance. Bill was an informal supervisor of our week end gliding activities. We released from a Chipmunk aero tow somewhere near Guildford under a growing cumulus cloud and were soon rapidly gaining height in the cloud. The air temperature kept reducing with increasing altitude and we began to wonder how much colder we could become before leaving the cloud.

The glider had a battery driven artificial horizon and direction indicator and Bill had been doing a good job with these instruments. But without us realising it initially, the battery was going flat and the AH started to lean over. Bill followed the AH until I noticed that the turn indicator was not making sense. Soon after we entered a steep spiral dive and speed rapidly increased. I watched in horror as the airspeed went on up over the red line, never exceed, speed of 92 Kts. Markings around the dial of the ASI were from 20 Kts to 110 Kts with a gap around the bottom 30 degrees of the dial. I watched the needle go around through the gap and continue until it was showing 25 Kts the second time around. I guess we were up around 150 Kts. Sincere thanks go to the Sedburgh designer for all of that excess strength.

The airflow noise was very high, the wings had unusual twists and I was using both hands pulling on the air-brake toggle with the feeling that if I pulled any harder I would break something. We hurtled out through the cloud base still well nose down and directly over the city of Guildford. Bill slowly brought the nose up and as the speed thankfully reduced we zoomed up to cloud base again. By now the AH was unusable and as we looked at each other with intense relief we both knew that there was no way we were going to re-enter the cloud to gain enough height for us to glide back to Farnborough.

Recognising that we were now too low to glide upwind to Farnborough Bill elected to try to glide downwind to the airfield at Dunsfold just visible in the distance. We hoped to be able to pick up some rising air on the way. Our gliding angle was obviously too great for us to reach Dunsfold directly so we headed off a little towards another cumulus hoping for some lift beneath it. But we were disappointed and realised that a forced landing was now most probable.

It was the time of the year when all of the wheat or other crops in the area were being harvested and there were bales of straw all over potential landing fields. We spotted a green field beyond a small forest and decided that this was to be our place to land. Having committed ourselves to this green field, there was then nowhere else to go. Alas we soon began to see that it was a wheat-field ready for harvesting.

I tightened my harness as much as possible expecting a sudden stop and that was just as well. Bill levelled off the glider just above the wheat and it brushed us loudly underneath. Eventually stalling we sank down into the wheat until our sight line was below the wheat. Suddenly the wings sank into the wheat and we stopped immediately with very rapid deceleration. The last foot or two was a vertical drop on to the ground with a teeth jarring crunch. There was no run-out of an arrestor cable as for a carrier landing.

Suddenly all was silence except that in the distance we could hear a few people yelling to each other. We had disappeared from anyone's view and local observers all believed from the noise generated by our arrestment that we had severely crashed.

Bill and I looked and grimaced at each other in relief and having assured ourselves that we were uninjured except for the sure knowledge that we would be suffering from bruises where the straps had done their job. We climbed out to find that we were just not tall enough to see over the top of the wheat. Having noted where the farmer's house was situated we carefully made our way along the rows of wheat in that general direction. On the way Bill explained that it would be normal for the farmer to extract compensation for that portion of his crop knocked down so we should take care to minimise damage.

Soon we were being treated to a cup of tea in the farmhouse whilst curious locals turned up from all directions. Someone had reported a crash to police and soon several police cars approached. Two policeman turned up on bicycles. One came on a horse. Then came an ambulance and Bill was able to talk the ambulance crew into giving him a few swigs of medicinal brandy to steady his nerves as he so eloquently put it. The policemen were eager to help so we used them in two teams to help manhandle the wings off the glider and move them and the fuselage into the farmer's barn ready for retrieval next day by trucks from Farnborough. Wish I had had a camera.

All that remained was the completion of an incident report and a structural inspection of the glider for overstress. It was duly pronounced to be still airworthy. Two weeks later it was used to give the Duke of Edinborough his first flight in a glider. I often wondered about its continued structural integrity.

The glider flight with Bill Bedford was not to be my last such hairy experience we shared. The next was in a Hunter 7 trainer sorting out severe rudder buzz pulling g supersonic.

We ETPS students all learned a great deal from each other and also from the tutors who were all TPs with recent experimental flight test experience. As well as the opportunities to mix it with some of the best practising test pilots in the world in an atmosphere devoted for almost a year to the pursuits of practical test flying, we learned to grasp the essentials for survival when involved with the rapid mastering of complex machines powered by a wide variety of piston and jet engines. We grew to appreciate the existing and developing standard requirements underlying the design and handling of numerous types of aircraft and their systems.

The reference for British aircraft design was a publication produced over the relatively few years of aircraft development called AVP970. During those days of rapid advancements resulting from the jet engine a world standard reference was also being derived under the auspices of the Advisory Group for Aviation Research and Development - AGARD. Metallurgy was being pushed to the utmost for both aircraft structures and jet engine turbine and compressor blades. Power to weight ratios for aircraft engines were rapidly reducing. We were indeed fortunate to be so close to all of this activity.

In the next post I try to quantify the differences between expert and not so expert pilots and test pilots in particular.

Memoirs continued.

Unfortunately LOMCEVAK those days are gone forever.

One Saturday afternoon at Farnborough I found myself sitting in the right seat of the ETPS Sedburg glider with Bill Bedford, the Harrier test pilot, in the left seat. Bill, a former ETPS tutor, was an enthusiastic glider pilot and at the time held several British gliding records for height and distance. Bill was an informal supervisor of our week end gliding activities. We released from a Chipmunk aero tow somewhere near Guildford under a growing cumulus cloud and were soon rapidly gaining height in the cloud. The air temperature kept reducing with increasing altitude and we began to wonder how much colder we could become before leaving the cloud.

The glider had a battery driven artificial horizon and direction indicator and Bill had been doing a good job with these instruments. But without us realising it initially, the battery was going flat and the AH started to lean over. Bill followed the AH until I noticed that the turn indicator was not making sense. Soon after we entered a steep spiral dive and speed rapidly increased. I watched in horror as the airspeed went on up over the red line, never exceed, speed of 92 Kts. Markings around the dial of the ASI were from 20 Kts to 110 Kts with a gap around the bottom 30 degrees of the dial. I watched the needle go around through the gap and continue until it was showing 25 Kts the second time around. I guess we were up around 150 Kts. Sincere thanks go to the Sedburgh designer for all of that excess strength.

The airflow noise was very high, the wings had unusual twists and I was using both hands pulling on the air-brake toggle with the feeling that if I pulled any harder I would break something. We hurtled out through the cloud base still well nose down and directly over the city of Guildford. Bill slowly brought the nose up and as the speed thankfully reduced we zoomed up to cloud base again. By now the AH was unusable and as we looked at each other with intense relief we both knew that there was no way we were going to re-enter the cloud to gain enough height for us to glide back to Farnborough.

Recognising that we were now too low to glide upwind to Farnborough Bill elected to try to glide downwind to the airfield at Dunsfold just visible in the distance. We hoped to be able to pick up some rising air on the way. Our gliding angle was obviously too great for us to reach Dunsfold directly so we headed off a little towards another cumulus hoping for some lift beneath it. But we were disappointed and realised that a forced landing was now most probable.

It was the time of the year when all of the wheat or other crops in the area were being harvested and there were bales of straw all over potential landing fields. We spotted a green field beyond a small forest and decided that this was to be our place to land. Having committed ourselves to this green field, there was then nowhere else to go. Alas we soon began to see that it was a wheat-field ready for harvesting.

I tightened my harness as much as possible expecting a sudden stop and that was just as well. Bill levelled off the glider just above the wheat and it brushed us loudly underneath. Eventually stalling we sank down into the wheat until our sight line was below the wheat. Suddenly the wings sank into the wheat and we stopped immediately with very rapid deceleration. The last foot or two was a vertical drop on to the ground with a teeth jarring crunch. There was no run-out of an arrestor cable as for a carrier landing.

Suddenly all was silence except that in the distance we could hear a few people yelling to each other. We had disappeared from anyone's view and local observers all believed from the noise generated by our arrestment that we had severely crashed.

Bill and I looked and grimaced at each other in relief and having assured ourselves that we were uninjured except for the sure knowledge that we would be suffering from bruises where the straps had done their job. We climbed out to find that we were just not tall enough to see over the top of the wheat. Having noted where the farmer's house was situated we carefully made our way along the rows of wheat in that general direction. On the way Bill explained that it would be normal for the farmer to extract compensation for that portion of his crop knocked down so we should take care to minimise damage.

Soon we were being treated to a cup of tea in the farmhouse whilst curious locals turned up from all directions. Someone had reported a crash to police and soon several police cars approached. Two policeman turned up on bicycles. One came on a horse. Then came an ambulance and Bill was able to talk the ambulance crew into giving him a few swigs of medicinal brandy to steady his nerves as he so eloquently put it. The policemen were eager to help so we used them in two teams to help manhandle the wings off the glider and move them and the fuselage into the farmer's barn ready for retrieval next day by trucks from Farnborough. Wish I had had a camera.

All that remained was the completion of an incident report and a structural inspection of the glider for overstress. It was duly pronounced to be still airworthy. Two weeks later it was used to give the Duke of Edinborough his first flight in a glider. I often wondered about its continued structural integrity.

The glider flight with Bill Bedford was not to be my last such hairy experience we shared. The next was in a Hunter 7 trainer sorting out severe rudder buzz pulling g supersonic.

We ETPS students all learned a great deal from each other and also from the tutors who were all TPs with recent experimental flight test experience. As well as the opportunities to mix it with some of the best practising test pilots in the world in an atmosphere devoted for almost a year to the pursuits of practical test flying, we learned to grasp the essentials for survival when involved with the rapid mastering of complex machines powered by a wide variety of piston and jet engines. We grew to appreciate the existing and developing standard requirements underlying the design and handling of numerous types of aircraft and their systems.

The reference for British aircraft design was a publication produced over the relatively few years of aircraft development called AVP970. During those days of rapid advancements resulting from the jet engine a world standard reference was also being derived under the auspices of the Advisory Group for Aviation Research and Development - AGARD. Metallurgy was being pushed to the utmost for both aircraft structures and jet engine turbine and compressor blades. Power to weight ratios for aircraft engines were rapidly reducing. We were indeed fortunate to be so close to all of this activity.

In the next post I try to quantify the differences between expert and not so expert pilots and test pilots in particular.

Join Date: Oct 2003

Location: Canberra Australia

Posts: 1,300

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Farnborough and ETPS Continued

From Unpublished Incomplete Memoirs covering most TP activities. Experience before ETPS, post flying training, was combat tour flying Mustangs in Korean war, QFI 3 yrs, CFS 2 yrs. Hours flown pre ETPS 2000, Types - Tiger Moth, Wirraway, Dakota, Mustang, Vampire, Lincoln, Valetta, S51 Helicopter, Sabre.

I found myself wondering how to define the level of a pilot's expertise and then how to apply similar definitions of levels to the test pilot. Why was a good pilot different from a bad pilot and how could this be quantified. My conclusions then have not changed much with increasing experience. A pilot or car driver or anyone handling equipment requiring a reasonable level of co-ordination is good or bad depending on his ability to contribute to the total control and feedback loops which combine to cause the machine to perform to the greatest satisfaction of the intended design. Generally with aircraft or cars or other means of human transportation, the ultimate aim is for the pilot/driver to control the machine in the smoothest and most efficient manner. Disturbances arising from external influences need to be smoothed out by compensating control inputs from the pilot. The inputs from the pilot need to be applied without abrupt transitions as they affect our normal senses and always within structural and performance limits.

It then follows that if a pilot has a high natural sensitivity to subtle acceleration forces he will be able to react at very low thresholds of these forces and achieve high levels of damping. The result is the smoothest possible progress.

This is best appreciated by two aspects of car driving. We are all very aware of the driver who allows a car to wander from side to side along a lane on a highway only taking corrective action by a deliberate turn of the steering wheel when his level of sensitivity at last detects an excursion which, to him, should be corrected. This driver does not apply slight pressures to the wheel to keep the deviations in check at low levels. Instead, he is more likely to deliberately and suddenly turn the wheel so that the unfortunate passengers are continually being subject to changing lateral accelerations which cause their heads to be forced from side to side. Translate this into four dimensions in an aircraft and it becomes easier to appreciate the differences between pilots.

The other part of car control, where almost universal malpractice persists, occurs during stopping. With brakes applied, the average driver fails to flair down the deceleration just before stopping. The result is an uncomfortable lurch when the deceleration abruptly stops. Many average pilots torture their more sensitive passengers and aircraft with the same treatment.

Smoothness of control is basic to good piloting. Smoothness can only be learned to a limited degree. High levels of natural sensitivity with all of the senses then provides the good pilot with an ability to detect a myriad of other inputs and cues providing extensions to his nervous system to encompass the total aircraft and its systems. Instruments provide further extensions in addition or where no natural cues are present.

As a passenger in an aircraft, I can readily tell the sensitivity of its pilot soon after taxying starts. If the brakes are released in such a manner that passengers lurch in their seats then the odds are there is an insensitive pilot in the feedback loop. If, when stopping the pilot does not flair off deceleration as speed approaches zero then we have another uncomfortable lurch situation. This is very common with insensitive or careless car drivers. The manner of use of nose-wheel steering gives another clear indication to the smoothness of a pilot before flight.

After taxying with a poor pilot, I know that I am in for poorly coordinated flight in the air. I also know from experience that the non smooth pilot will have difficulty in handling abnormal circumstances. He may be able to do it by rote or by the book but there will be that edge of finesse which will always be missing.

Recognition by the test pilot of the limitations of the whole range of pilots leads to the definition of safety margins covering almost all aspects of aircraft handling, control and cockpit design. Obviously, the test pilot can hardly describe the stability of an aircraft as satisfactory if only he is able to fly it. He must always be aware of the limitations of the worst pilot who may be permitted to fly. The result of all the derived limitations and standard requirements is that today we have aircraft which are all easy and safe for the average pilot to fly. As pilot ability decreases from the average, his degree of difficulty rises but rarely to the extent where a desired level of safety is jeopardised.

The TPS course could not possibly cover the vast range of engineering and manufacturing aspects of aviation in any detail but it was instrumental in giving us the basis for design and handling and making us aware of the significant responsibilities we would have in the future to ensure that the established design philosophies continued to be upheld and improved.

Significantly also, the ETPS course gave us the confidence and indeed the ability to be able to make adequate preparation to climb in to yet another aircraft type and be able to make adequate preparations for the first flight of a newly designed or modified aircraft. We became expert in recognising the essentials whilst deliberately discarding the non-essentials in launching an aircraft and in being able to cope with malfunctions of any sort. We became expert at observing and recording intricate details on our knee pads or into tape recorders whilst doing all required to operate an aircraft safely to the edges of their handling and performance envelopes. All of this was in an environment which, on most flights, was all but friendly and always variable.

Aircraft cockpit standardisation was still in its infancy so we had to cope with a great variety of switches, levers, indicators and instruments to achieve similar results. We were essentially the "standard man" as detailed in the AVP970 and so became very aware of man's physical limitations of reach, muscular strengths, vision day/night, tactile feel and all of these within the unforgiving realities of g forces, oxygen supply and extremes of temperature. It was not until the early 60s that we TPs were able to collectively insist on all vital cockpit controls being arranged so that switches and levers be all forward or up for take-off.

We had come a long way in a very short time since the Wright brothers and Cody at Farnborough. Before their first tentative flights, man had for some centuries been preoccupied with attempts to emulate birds. Knowledge of the properties of air flowing around objects puzzled engineers for many years. Basic knowledge of stability and control essential for safe flight took many generations to develop.

From Unpublished Incomplete Memoirs covering most TP activities. Experience before ETPS, post flying training, was combat tour flying Mustangs in Korean war, QFI 3 yrs, CFS 2 yrs. Hours flown pre ETPS 2000, Types - Tiger Moth, Wirraway, Dakota, Mustang, Vampire, Lincoln, Valetta, S51 Helicopter, Sabre.

I found myself wondering how to define the level of a pilot's expertise and then how to apply similar definitions of levels to the test pilot. Why was a good pilot different from a bad pilot and how could this be quantified. My conclusions then have not changed much with increasing experience. A pilot or car driver or anyone handling equipment requiring a reasonable level of co-ordination is good or bad depending on his ability to contribute to the total control and feedback loops which combine to cause the machine to perform to the greatest satisfaction of the intended design. Generally with aircraft or cars or other means of human transportation, the ultimate aim is for the pilot/driver to control the machine in the smoothest and most efficient manner. Disturbances arising from external influences need to be smoothed out by compensating control inputs from the pilot. The inputs from the pilot need to be applied without abrupt transitions as they affect our normal senses and always within structural and performance limits.

It then follows that if a pilot has a high natural sensitivity to subtle acceleration forces he will be able to react at very low thresholds of these forces and achieve high levels of damping. The result is the smoothest possible progress.

This is best appreciated by two aspects of car driving. We are all very aware of the driver who allows a car to wander from side to side along a lane on a highway only taking corrective action by a deliberate turn of the steering wheel when his level of sensitivity at last detects an excursion which, to him, should be corrected. This driver does not apply slight pressures to the wheel to keep the deviations in check at low levels. Instead, he is more likely to deliberately and suddenly turn the wheel so that the unfortunate passengers are continually being subject to changing lateral accelerations which cause their heads to be forced from side to side. Translate this into four dimensions in an aircraft and it becomes easier to appreciate the differences between pilots.

The other part of car control, where almost universal malpractice persists, occurs during stopping. With brakes applied, the average driver fails to flair down the deceleration just before stopping. The result is an uncomfortable lurch when the deceleration abruptly stops. Many average pilots torture their more sensitive passengers and aircraft with the same treatment.

Smoothness of control is basic to good piloting. Smoothness can only be learned to a limited degree. High levels of natural sensitivity with all of the senses then provides the good pilot with an ability to detect a myriad of other inputs and cues providing extensions to his nervous system to encompass the total aircraft and its systems. Instruments provide further extensions in addition or where no natural cues are present.

As a passenger in an aircraft, I can readily tell the sensitivity of its pilot soon after taxying starts. If the brakes are released in such a manner that passengers lurch in their seats then the odds are there is an insensitive pilot in the feedback loop. If, when stopping the pilot does not flair off deceleration as speed approaches zero then we have another uncomfortable lurch situation. This is very common with insensitive or careless car drivers. The manner of use of nose-wheel steering gives another clear indication to the smoothness of a pilot before flight.

After taxying with a poor pilot, I know that I am in for poorly coordinated flight in the air. I also know from experience that the non smooth pilot will have difficulty in handling abnormal circumstances. He may be able to do it by rote or by the book but there will be that edge of finesse which will always be missing.

Recognition by the test pilot of the limitations of the whole range of pilots leads to the definition of safety margins covering almost all aspects of aircraft handling, control and cockpit design. Obviously, the test pilot can hardly describe the stability of an aircraft as satisfactory if only he is able to fly it. He must always be aware of the limitations of the worst pilot who may be permitted to fly. The result of all the derived limitations and standard requirements is that today we have aircraft which are all easy and safe for the average pilot to fly. As pilot ability decreases from the average, his degree of difficulty rises but rarely to the extent where a desired level of safety is jeopardised.

The TPS course could not possibly cover the vast range of engineering and manufacturing aspects of aviation in any detail but it was instrumental in giving us the basis for design and handling and making us aware of the significant responsibilities we would have in the future to ensure that the established design philosophies continued to be upheld and improved.

Significantly also, the ETPS course gave us the confidence and indeed the ability to be able to make adequate preparation to climb in to yet another aircraft type and be able to make adequate preparations for the first flight of a newly designed or modified aircraft. We became expert in recognising the essentials whilst deliberately discarding the non-essentials in launching an aircraft and in being able to cope with malfunctions of any sort. We became expert at observing and recording intricate details on our knee pads or into tape recorders whilst doing all required to operate an aircraft safely to the edges of their handling and performance envelopes. All of this was in an environment which, on most flights, was all but friendly and always variable.

Aircraft cockpit standardisation was still in its infancy so we had to cope with a great variety of switches, levers, indicators and instruments to achieve similar results. We were essentially the "standard man" as detailed in the AVP970 and so became very aware of man's physical limitations of reach, muscular strengths, vision day/night, tactile feel and all of these within the unforgiving realities of g forces, oxygen supply and extremes of temperature. It was not until the early 60s that we TPs were able to collectively insist on all vital cockpit controls being arranged so that switches and levers be all forward or up for take-off.

We had come a long way in a very short time since the Wright brothers and Cody at Farnborough. Before their first tentative flights, man had for some centuries been preoccupied with attempts to emulate birds. Knowledge of the properties of air flowing around objects puzzled engineers for many years. Basic knowledge of stability and control essential for safe flight took many generations to develop.

Milt,

I assume that you had a "Preview" exercise at the end of your ETPS course. I am interested in how this has changed over the years. Some details of your "Preview" would be interesting for the next chapter!

Rgds

L

I assume that you had a "Preview" exercise at the end of your ETPS course. I am interested in how this has changed over the years. Some details of your "Preview" would be interesting for the next chapter!

Rgds

L

Do a Hover - it avoids G

Join Date: Oct 1999

Location: Chichester West Sussex UK

Age: 91

Posts: 2,206

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

LOMCEVAK

Interesting point. I too look forward to Milt’s response.

I was nine years after Milt (1963 22 Course) and then only a ‘standard’ ETPS type written report was expected. Naturally the type was always one you had not flown before.

Preparation was I suspect different from today. The briefing I got was “You are doing your preview on the Javelin. Assess it in the all weather fighter role. There is one at Armament Flight and they are expecting you.”

Since we were (deliberately?) given no clues as to how we were being assessed on this exercise, I chose to presume that I was expected to brief myself. So I spoke to nobody – beyond liaising with the aircraft owner’s engineers for access and the 700 serviceability paperwork. I also got the impression that they had been told not to help me as nobody entered into any conversation beyond answers to my questions regarding access and availability, which is a tad unusual if you think about the way a day to day visitor would normally be treated.

There was a set of Pilot’s Notes in the cockpit stowage – and I remember after reading the system description and limitations pages that I felt a cheat when looking at the handling notes as real test pilots did not have those.

JF

Interesting point. I too look forward to Milt’s response.

I was nine years after Milt (1963 22 Course) and then only a ‘standard’ ETPS type written report was expected. Naturally the type was always one you had not flown before.

Preparation was I suspect different from today. The briefing I got was “You are doing your preview on the Javelin. Assess it in the all weather fighter role. There is one at Armament Flight and they are expecting you.”

Since we were (deliberately?) given no clues as to how we were being assessed on this exercise, I chose to presume that I was expected to brief myself. So I spoke to nobody – beyond liaising with the aircraft owner’s engineers for access and the 700 serviceability paperwork. I also got the impression that they had been told not to help me as nobody entered into any conversation beyond answers to my questions regarding access and availability, which is a tad unusual if you think about the way a day to day visitor would normally be treated.

There was a set of Pilot’s Notes in the cockpit stowage – and I remember after reading the system description and limitations pages that I felt a cheat when looking at the handling notes as real test pilots did not have those.

JF

Join Date: Nov 2003

Location: In a good pub (I wish!)

Posts: 250

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

JF,

Come on, don't stop there. Or are you going to be like Milt and let out your story a bit at a time. If so, remember to always leave it on a cliff hangar (hangar?).

Come on, don't stop there. Or are you going to be like Milt and let out your story a bit at a time. If so, remember to always leave it on a cliff hangar (hangar?).

Do a Hover - it avoids G

Join Date: Oct 1999

Location: Chichester West Sussex UK

Age: 91

Posts: 2,206

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

TD&H

Sorry, nothing much more to add really. Like any end of course exam in my experience I knew what I was supposed to do, so just had to get on with it. As ever the Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations were the only part that required burning the midnight oil and polishing and polishing and polishing since those were the bits that mattered and enabled you to show (or not) that you understood what the tp’s job was all about. If you could not plan the trips, execute them and write up the main body of the report by then there was not going to be much hope for you as these were just pages of factual grind such as Weather Time and Place, Tests Carried Out, and Test Results.

Since the only other fighter of the day I had any time on was the Hunter (which in my view was one of the worst handling/more useless modern aircraft that Kingston/Dunsfold foisted on the world) I can remember to this day the surprise I felt as I unstuck on my first takeoff in the Javelin. The thing was instantly rock steady, easy to trim hands off and subsequently stable in roll and pitch on the climb. Now that is what you want to fly in cloud or at night. If you are a Hunter man you will know that none of those Javelin attributes applied to the Hunter - a very pretty aeroplane that everybody got a great kick out of poling round the sky. (Great for an exciting ride but fit for the purpose it was purchased …..you have to be joking)

Mind you a pair of donks in an all weather fighter that suffered from centreline closure rather made a mess of the whole enterprise. (Centre line closure being contraction of the compressor casing when hit by cold moist air so that it grabbed the rotating bits…….)

JF

Sorry, nothing much more to add really. Like any end of course exam in my experience I knew what I was supposed to do, so just had to get on with it. As ever the Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations were the only part that required burning the midnight oil and polishing and polishing and polishing since those were the bits that mattered and enabled you to show (or not) that you understood what the tp’s job was all about. If you could not plan the trips, execute them and write up the main body of the report by then there was not going to be much hope for you as these were just pages of factual grind such as Weather Time and Place, Tests Carried Out, and Test Results.

Since the only other fighter of the day I had any time on was the Hunter (which in my view was one of the worst handling/more useless modern aircraft that Kingston/Dunsfold foisted on the world) I can remember to this day the surprise I felt as I unstuck on my first takeoff in the Javelin. The thing was instantly rock steady, easy to trim hands off and subsequently stable in roll and pitch on the climb. Now that is what you want to fly in cloud or at night. If you are a Hunter man you will know that none of those Javelin attributes applied to the Hunter - a very pretty aeroplane that everybody got a great kick out of poling round the sky. (Great for an exciting ride but fit for the purpose it was purchased …..you have to be joking)

Mind you a pair of donks in an all weather fighter that suffered from centreline closure rather made a mess of the whole enterprise. (Centre line closure being contraction of the compressor casing when hit by cold moist air so that it grabbed the rotating bits…….)

JF

Join Date: Jul 2004

Location: Longton, Lancs, UK

Age: 80

Posts: 1,527

Likes: 0

Received 1 Like

on

1 Post

JF

I suspect that your comments concering the beloved Hunter were meant to be provocative! Being not a TP, albeit I'm a friend of some, I flew the beast for around 3000 hours in various roles and thought it was a delight to fly. As, I suspect, did thousands of others. If you are observing the beast from a purely analytical view, I might forgive you - to a very small degree.

C'mon - own up: you're being tweeky!

I suspect that your comments concering the beloved Hunter were meant to be provocative! Being not a TP, albeit I'm a friend of some, I flew the beast for around 3000 hours in various roles and thought it was a delight to fly. As, I suspect, did thousands of others. If you are observing the beast from a purely analytical view, I might forgive you - to a very small degree.

C'mon - own up: you're being tweeky!

Last edited by jindabyne; 14th Dec 2004 at 09:59.

I only have a very few hours on the Hunter but would certainly agree with what JF said. The control harmony was nice at around 420KIAS, but it got much twitchier at higher speeds - and at low speeds the converse applied. Hardly surprising as it was really only 'power steering' which, if I recall correctly, didn't have anything to modify gain with respect to speed? The fuel system was chaotic with wildly bouncing gauges which were useless during simulated ACM or in turbulence - and whoever put those CBs back behind the right side of the cockpit was surely having a laugh. You needed the skills of James Herriot to find them and reset them! Reaching the electrical gang bar and AvPin starter button was almost impossible in the Mk 2 bonedome; clearly ergonomics was still in the 'spray glue around cockpit, then throw in bucket of dials, knobs and tits and bolt them in where they stick' era!

Using 23 flap to help the instantaneous turn rate was a known technique - but if it was left down above M0.9 the thing would enter a dive from which recovery was impossible unless flap was first retracted. It's though that's what killed a guy when I was at Brawdy.

At low level even we students felt part of a Gnat with its great view out, responsive controls plus good compass and stopwatch - a feeling that one didn't quite get in the HUnter.

But we all loved the Hunter, of course - even with its not inconsiderable foibles!

A TP once told me a story about flying the last Javelin from Boscombe. Somewhere over Wales they suddenly realised that a Significant Cock-Up had occurred with fuel planning and, as a result, they didn't have much left. On contacting some Air Trafficker or other they were given the usual 'Turn right 90 deg for identification' thinng, to which the TP replied: "Madam, I am flying the world's only remaining Javelin. If I do what you want the world will soon have one less!". I believe they made it back to Boscombe - just. Or may have landed at Lyneham - can't recall.

Using 23 flap to help the instantaneous turn rate was a known technique - but if it was left down above M0.9 the thing would enter a dive from which recovery was impossible unless flap was first retracted. It's though that's what killed a guy when I was at Brawdy.

At low level even we students felt part of a Gnat with its great view out, responsive controls plus good compass and stopwatch - a feeling that one didn't quite get in the HUnter.

But we all loved the Hunter, of course - even with its not inconsiderable foibles!

A TP once told me a story about flying the last Javelin from Boscombe. Somewhere over Wales they suddenly realised that a Significant Cock-Up had occurred with fuel planning and, as a result, they didn't have much left. On contacting some Air Trafficker or other they were given the usual 'Turn right 90 deg for identification' thinng, to which the TP replied: "Madam, I am flying the world's only remaining Javelin. If I do what you want the world will soon have one less!". I believe they made it back to Boscombe - just. Or may have landed at Lyneham - can't recall.

Join Date: Nov 2001

Location: 18nm N of LGW

Posts: 238

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

TEST PILOT's

THIS thread is just one such thread I have been hoping to see for many a long day. It has 'grown' considerably over the past few weeks with Milt's inputs. It is clear that my two friends LOMCEVAK and John Farley are getting the taste by adding to a fascinating subject that IS Aviation History and Nostalgia. I am glued to each post!

For that reason, if no other, I am keeping this thread in constant view and hope that the inputs from those I mention, and others who have, and do, make such interesting contributions, will continue to enthrall the avid admirers in this place of their very special past.

Please keep the stories coming. There must be literally hundreds!

THIS thread is just one such thread I have been hoping to see for many a long day. It has 'grown' considerably over the past few weeks with Milt's inputs. It is clear that my two friends LOMCEVAK and John Farley are getting the taste by adding to a fascinating subject that IS Aviation History and Nostalgia. I am glued to each post!

For that reason, if no other, I am keeping this thread in constant view and hope that the inputs from those I mention, and others who have, and do, make such interesting contributions, will continue to enthrall the avid admirers in this place of their very special past.

Please keep the stories coming. There must be literally hundreds!

Do a Hover - it avoids G

Join Date: Oct 1999

Location: Chichester West Sussex UK

Age: 91

Posts: 2,206

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

Jindabyne

Sorry if you disagree with my views but no I was not being ‘tweaky’. The short answer is that it is a test pilots job to find fault (whereas it is a squadron pilot’s job to cope by compensating for any aircraft deficiencies – and very well they do that too)

The longer answer is that you will never hear much said against the Hunter by those on Hunter Squadrons because that is the nature of squadron pilots. Their job is to do the best with what they have and so it is not in the culture of such units to suggest they find anything difficult – let alone too difficult. When the Hunter replaced the Venom and Meteor it offered a startling improvement in top speed, rate of climb and even service ceiling. So of course it was THE aeroplane to fly, it bored magnificent holes in the sky and its foibles enabled the talented to show that they were better than other less talented squadron mates. In point of fact what they were showing was that they were better at compensating for the aircraft’s weaknesses.

I am certainly of the view that if the Hunter had to be used for what it was procured to do (at least in the late 50’s and early 60’s) then it would have struggled. By then friends and enemies used all flying tailplanes and had basic nav aids as well - while some were even supersonic in level flight. It really was not good enough to offer pilots a GIV compass (tucked away behind the stick) and a map as a means of doing their business. The way new pilots waggled their way into the sky was nothing for Kingston/Dunsfold to be proud of. Even when it went out of service it still did not have an effective lateral trim system. It was all too easy to dutch roll in manual (which killed a very experienced pilot at Dunsfold not many years ago) while pitch up at low speed was something that the pilot was required to avoid by the use of skill.

Having said all that I do admit that my views are those of a professional critic. My appreciation of the Hunter started one day in 1954 at RAE Farnborough when as a flight test observer I had just got out of an NGTE Lincoln that was fitted with a reheated Derwent under the fuselage. My pilot, Flt Lt Norman Kearney fell into conversation with Flt Lt Taffy Ecclestone who had just got out of a Hunter and was clearly exercised by his recent gun firing experiences (as befitted my station I stood in awe of these men).

Taffy told Norman that he for one had had enough of gliding around day after day just because he had fired a fighter’s guns and was off to join the Handley Page team on the Victor as that had four engines and they all seemed to keep going as well. Flt Lt Roger Topp joined in and believe you me these men (and others at RAE at that time) knew when an aeroplane was not as good as it should have been.

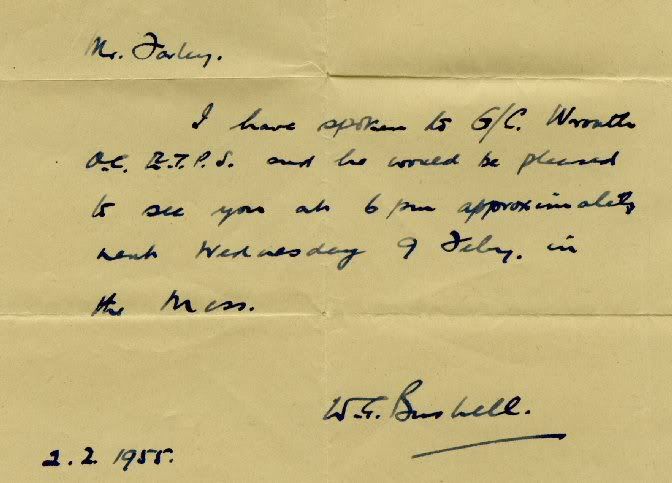

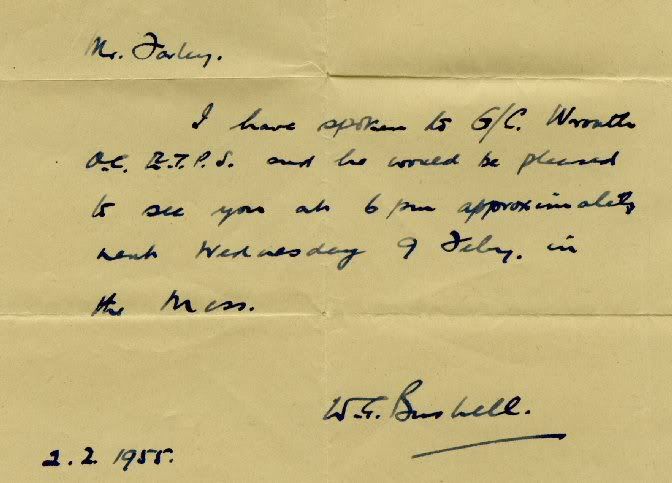

If you like during my five years at RAE (50 – 55) I was conditioned by the boffins and tp’s to the point where all I wanted to do was be part of the business of making better aeroplanes. So I did not join the RAF because I wanted to be an RAF pilot but because I needed them to teach me to fly. I wangled an interview with the Commandant of ETPS Gp Capt Sammy Wroath thanks to a letter of introduction from one of the boffins.

[IMG] [/IMG]

[/IMG]

The Great Man asked me a bunch of questions the first being ‘Why do you want to be a test pilot?’ (BTW in my book that is the No1 question to ask anybody applying for any job) and after 45 mins he stood on the steps of the mess and said that I seemed just the sort of young chap they liked to have at the school - but that I would have to go away and learn to fly first….. As I walked down the drive from the mess towards my YMCA hostel I thought no sweat, the RAF will teach me that (but there you go without the arrogance of youth not much progess would ever be made eh?).

Norman is till very much alive and kicking – I sent him his Xmas card yesterday, Taffy was killed in his Victor following flutter only a month or so later and Sammy died some five years ago. Sammy was tickled pink when I went and saw him after passing ETPS in 63.

After getting my wings I joined 4 Sqn at Jever in ‘58 when they were just changing from Hunter IVs to 6’s. Like you for the first six months I just enjoyed one of the best rides in the business, but by the end of my tour I could see how we were all kidding ourselves if we thought we could have coped with the WP. So I was really pleased to go and do what I saw as a ‘proper’ and worthwhile job - QFI on the JP3 at Barkston. Now NO proper fighter pilot would EVER say anything like that eh? Half way through Barkston they sent me to ETPS. Bingo.

JF

Sorry if you disagree with my views but no I was not being ‘tweaky’. The short answer is that it is a test pilots job to find fault (whereas it is a squadron pilot’s job to cope by compensating for any aircraft deficiencies – and very well they do that too)

The longer answer is that you will never hear much said against the Hunter by those on Hunter Squadrons because that is the nature of squadron pilots. Their job is to do the best with what they have and so it is not in the culture of such units to suggest they find anything difficult – let alone too difficult. When the Hunter replaced the Venom and Meteor it offered a startling improvement in top speed, rate of climb and even service ceiling. So of course it was THE aeroplane to fly, it bored magnificent holes in the sky and its foibles enabled the talented to show that they were better than other less talented squadron mates. In point of fact what they were showing was that they were better at compensating for the aircraft’s weaknesses.

I am certainly of the view that if the Hunter had to be used for what it was procured to do (at least in the late 50’s and early 60’s) then it would have struggled. By then friends and enemies used all flying tailplanes and had basic nav aids as well - while some were even supersonic in level flight. It really was not good enough to offer pilots a GIV compass (tucked away behind the stick) and a map as a means of doing their business. The way new pilots waggled their way into the sky was nothing for Kingston/Dunsfold to be proud of. Even when it went out of service it still did not have an effective lateral trim system. It was all too easy to dutch roll in manual (which killed a very experienced pilot at Dunsfold not many years ago) while pitch up at low speed was something that the pilot was required to avoid by the use of skill.

Having said all that I do admit that my views are those of a professional critic. My appreciation of the Hunter started one day in 1954 at RAE Farnborough when as a flight test observer I had just got out of an NGTE Lincoln that was fitted with a reheated Derwent under the fuselage. My pilot, Flt Lt Norman Kearney fell into conversation with Flt Lt Taffy Ecclestone who had just got out of a Hunter and was clearly exercised by his recent gun firing experiences (as befitted my station I stood in awe of these men).

Taffy told Norman that he for one had had enough of gliding around day after day just because he had fired a fighter’s guns and was off to join the Handley Page team on the Victor as that had four engines and they all seemed to keep going as well. Flt Lt Roger Topp joined in and believe you me these men (and others at RAE at that time) knew when an aeroplane was not as good as it should have been.

If you like during my five years at RAE (50 – 55) I was conditioned by the boffins and tp’s to the point where all I wanted to do was be part of the business of making better aeroplanes. So I did not join the RAF because I wanted to be an RAF pilot but because I needed them to teach me to fly. I wangled an interview with the Commandant of ETPS Gp Capt Sammy Wroath thanks to a letter of introduction from one of the boffins.

[IMG]

[/IMG]

[/IMG] The Great Man asked me a bunch of questions the first being ‘Why do you want to be a test pilot?’ (BTW in my book that is the No1 question to ask anybody applying for any job) and after 45 mins he stood on the steps of the mess and said that I seemed just the sort of young chap they liked to have at the school - but that I would have to go away and learn to fly first….. As I walked down the drive from the mess towards my YMCA hostel I thought no sweat, the RAF will teach me that (but there you go without the arrogance of youth not much progess would ever be made eh?).

Norman is till very much alive and kicking – I sent him his Xmas card yesterday, Taffy was killed in his Victor following flutter only a month or so later and Sammy died some five years ago. Sammy was tickled pink when I went and saw him after passing ETPS in 63.

After getting my wings I joined 4 Sqn at Jever in ‘58 when they were just changing from Hunter IVs to 6’s. Like you for the first six months I just enjoyed one of the best rides in the business, but by the end of my tour I could see how we were all kidding ourselves if we thought we could have coped with the WP. So I was really pleased to go and do what I saw as a ‘proper’ and worthwhile job - QFI on the JP3 at Barkston. Now NO proper fighter pilot would EVER say anything like that eh? Half way through Barkston they sent me to ETPS. Bingo.

JF

Last edited by John Farley; 13th Dec 2004 at 19:57.

Join Date: Oct 2003

Location: Canberra Australia

Posts: 1,300

Likes: 0

Received 0 Likes

on

0 Posts

This post completes my memoirs concerning Farnborough.

I must disappoint those wanting some details of my "Preview" of the Canberra as my final ETPS event as I will be hard pressed to separate it from an actual Preview I later conducted on the RAAF's first 'trainer' Canberra which required extensive refit to reach anything close to acceptable.

ETPS at Farnborough continued.

Many early "test pilots" were killed in their unflyable contraptions. One early would be aviator, in the interest of self preservation, proposed," there would be stronger and steadier winds over a lake than over the land, and the selection of a sheet of water to experiment over was very happy, as it would furnish a yielding bed to fall into if anything went wrong, as is pretty certain to happen on the first trials."

Fortunately, we English speaking pilots benefited with the world standard aviation language being English. Standards of measurement gradually became focussed and assigned to the sub-conscious. Some were always a stumbling block. The RAF used yards to measure the lengths of runways whereas the rest of the world was more content with feet. Mach Numbers were a new measure and added a third dimension to the way an aircraft performed. The relation between Mach No, Indicated air speed and True airspeed had to be fully appreciated. Heights and altitudes persist in feet and speed in Mach No or knots, distance predominantly in nautical miles, loads confusingly going through a slow change to metric measures and fuel changing from gallons to pounds. I had already gone through a transition from Miles per Hour to Knots during flying training when one had to closely identify which type of airspeed indicator happened to be fitted to the aircraft about to be flown.

By the end of the Test Pilot Course, I realised that although I had a graduation certificate, I was far from being satisfied that I could readily tackle any flight test task which may become my responsibility. Fortunately, my predecessors who would be my supervisors for the next few years had also had similar misgivings and there was an accepted pecking order of capability amongst the test pilot fraternity. There were also good and not so good test pilots considering their ability to satisfy the stringent demands for each to have a very broad depth of knowledge and the manipulative skills to go with such knowledge. Most gravitated to their areas of best capabilities. Others failed to recognise adequately their own limitations and either came to a sudden end or were eliminated by the fraternity.

We also learned that the vast majority of test flying would be very routine, interspersed liberally with those highlights which are generally considered to be the norm of the TP. The developing TP gradually enhances his feel for aircraft and the atmospheric medium. Subtle vibrations, tiny forces, movements, sounds and other cues begin to be translated into meaningful messages and signs which are not appreciated to the same extent by the average pilot. The TP's enhanced sensitivities to his machine extend from fingertips, seat of the pants feelings, visual and audible inputs to give the TP a complete and continuous feedback loop. He strives to make all of his controlling inputs into this complex relationship between man and machine as smoothly as possible, while maintaining close monitoring over any aberrations to expectations and reactions to his inputs. Special instrumentation recordings provide long term extensions to the TP's sensibilities.

Conflicts arise when other regimes attempt to insert impediments to the TP's feedback loops. For reasons of safety, physiological comfort and personal longevity a variety of these impediments have been imposed on aircrew. Wearing of gloves is not normally for the purpose of keeping hands warm. They are for protection, primarily against fire and to be a barrier against the extremely low temperatures should one have to eject at high altitude. The same applies to footwear, with military aircrew now wearing heavy boots. Both of these are simple examples where the result is a severe reduction in the sensitivity feedback loops for the TP. Whenever I needed high sensitivity I would have my gloves in my flying suit pocket.

Early powered flying control systems made the tasks of the TP more difficult. High break out forces and artificial feel severed or drastically reduced the primary feedback loop for the TP and made it necessary to compensate as best he could.

By now we were fully immersed in the course with the pressures of data analysis and report writing increasing. Flt Lt Dick Wittman developed a grounding medical condition about mid way through the course. He had been pre-chosen to follow on from the course to an exchange post with the RAF flight test centre at Boscombe Down near Salisbury in Wiltshire. With Dick's departure from the course I was advised that I would now take up this exchange posting. I was elated with the prospect and began to make arrangements to bring the family to England.

During 1955, the RAAF was evaluating a replacement for the MK35 two seat Vampire trainer. The British Jet Provost was on its list of contenders. I was tasked to fly an evaluation, which TPs termed a Pilot's assessment. I was thus diverted from the course for a few days to go to Luton for a 50 minute flight in a civil registered Jet Provost GA-OBU. My assessment was prepared using notes written on my knee pad against a pre-flight test format. I may never know how useful that report may have been in the RAAF's decision to equip with the Italian Macchi..

The course finished during the second week in December. I made my last flight at TPS on 14 November to complete the Preview on the Canberra. My flying hours on the course were 112.30, with total hours of 2280.

During the last few days of the course, some of the tutors arranged for a flight in an Avro Ashton, then at Boscombe Down. The Ashton had a Tudor fuselage, modified with a nose wheel and fitted with four Rolls Royce Nene engines. Six of these had been ordered by the RAF for high altitude research. The first of these, WB490, was the one assigned to Boscombe Down. It had two partly underslung engine nacelles, each containing two engines in wings with about 15 degrees sweep back of the wing leading edges. Wing span was 120 feet; AUW 72,000 pnds.

I became a member of a group to fly to Boscombe Down where the Ashton was flying some circuits. We climbed into the Ashton after it completed a circuit and whilst it was holding for a re take-off. This was my first flight in a prototype large four engined jet. We completed about five circuits with pilots rotating through the cockpit. To my disappointment, a malfunction in one of the engines prevented me from flying this aircraft.

Sqn Ldr Fred Cousins and Flt Lt Ken (Black) Murray were posted back to the RAAF's Aircraft Research and Development Unit at Laverton. Fred picked up along the way the responsibility for continued test flying on one of the small scale delta aircraft built by AVRO as development tools for the Vulcan. The aircraft, to be used for extended low speed research, was still at Boscombe Down. On 5 December, I accompanied Fred to Boscombe Down where he was to have a few familiarity flights. I managed to fly this aircraft, the Avro 707B, on 6 December for 20 minutes. It was to be the first of my many flights, over the next two years, in the mature version, the Vulcan B Mk1, from Boscombe Down.

So ends the story of a rapid learning curve produced by the Empire Test Pilots' School with Farnborough having been a dominating proving ground. What lay in store for me at Boscombe Down following my first assignment to investigate the spinning characteristics of a Mk 9 Auster ?

This thread will be best kept for anecdotes about Farnborough and I for one will be most grateful for posts covering the early periods of historic Farnborough.

Another thread on Flight Testing at Boscombe Down is bound to produce a series of stories that will otherwise be lost to posterity.

I must disappoint those wanting some details of my "Preview" of the Canberra as my final ETPS event as I will be hard pressed to separate it from an actual Preview I later conducted on the RAAF's first 'trainer' Canberra which required extensive refit to reach anything close to acceptable.

ETPS at Farnborough continued.

Many early "test pilots" were killed in their unflyable contraptions. One early would be aviator, in the interest of self preservation, proposed," there would be stronger and steadier winds over a lake than over the land, and the selection of a sheet of water to experiment over was very happy, as it would furnish a yielding bed to fall into if anything went wrong, as is pretty certain to happen on the first trials."

Fortunately, we English speaking pilots benefited with the world standard aviation language being English. Standards of measurement gradually became focussed and assigned to the sub-conscious. Some were always a stumbling block. The RAF used yards to measure the lengths of runways whereas the rest of the world was more content with feet. Mach Numbers were a new measure and added a third dimension to the way an aircraft performed. The relation between Mach No, Indicated air speed and True airspeed had to be fully appreciated. Heights and altitudes persist in feet and speed in Mach No or knots, distance predominantly in nautical miles, loads confusingly going through a slow change to metric measures and fuel changing from gallons to pounds. I had already gone through a transition from Miles per Hour to Knots during flying training when one had to closely identify which type of airspeed indicator happened to be fitted to the aircraft about to be flown.

By the end of the Test Pilot Course, I realised that although I had a graduation certificate, I was far from being satisfied that I could readily tackle any flight test task which may become my responsibility. Fortunately, my predecessors who would be my supervisors for the next few years had also had similar misgivings and there was an accepted pecking order of capability amongst the test pilot fraternity. There were also good and not so good test pilots considering their ability to satisfy the stringent demands for each to have a very broad depth of knowledge and the manipulative skills to go with such knowledge. Most gravitated to their areas of best capabilities. Others failed to recognise adequately their own limitations and either came to a sudden end or were eliminated by the fraternity.

We also learned that the vast majority of test flying would be very routine, interspersed liberally with those highlights which are generally considered to be the norm of the TP. The developing TP gradually enhances his feel for aircraft and the atmospheric medium. Subtle vibrations, tiny forces, movements, sounds and other cues begin to be translated into meaningful messages and signs which are not appreciated to the same extent by the average pilot. The TP's enhanced sensitivities to his machine extend from fingertips, seat of the pants feelings, visual and audible inputs to give the TP a complete and continuous feedback loop. He strives to make all of his controlling inputs into this complex relationship between man and machine as smoothly as possible, while maintaining close monitoring over any aberrations to expectations and reactions to his inputs. Special instrumentation recordings provide long term extensions to the TP's sensibilities.

Conflicts arise when other regimes attempt to insert impediments to the TP's feedback loops. For reasons of safety, physiological comfort and personal longevity a variety of these impediments have been imposed on aircrew. Wearing of gloves is not normally for the purpose of keeping hands warm. They are for protection, primarily against fire and to be a barrier against the extremely low temperatures should one have to eject at high altitude. The same applies to footwear, with military aircrew now wearing heavy boots. Both of these are simple examples where the result is a severe reduction in the sensitivity feedback loops for the TP. Whenever I needed high sensitivity I would have my gloves in my flying suit pocket.

Early powered flying control systems made the tasks of the TP more difficult. High break out forces and artificial feel severed or drastically reduced the primary feedback loop for the TP and made it necessary to compensate as best he could.

By now we were fully immersed in the course with the pressures of data analysis and report writing increasing. Flt Lt Dick Wittman developed a grounding medical condition about mid way through the course. He had been pre-chosen to follow on from the course to an exchange post with the RAF flight test centre at Boscombe Down near Salisbury in Wiltshire. With Dick's departure from the course I was advised that I would now take up this exchange posting. I was elated with the prospect and began to make arrangements to bring the family to England.